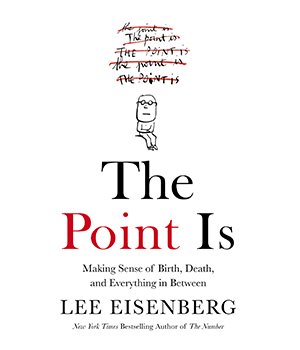

Lee Eisenberg, best-selling author of “The Number” and former editor in chief of Esquire magazine, has written a new book, “The Point Is: Making Sense of Birth, Death, and Everything in Between,” which grapples with the ongoing search for meaning and fulfillment in life. Make It Better recently had the opportunity to ask Eisenberg about our favorite parts of this compelling read.

Lee Eisenberg, best-selling author of “The Number” and former editor in chief of Esquire magazine, has written a new book, “The Point Is: Making Sense of Birth, Death, and Everything in Between,” which grapples with the ongoing search for meaning and fulfillment in life. Make It Better recently had the opportunity to ask Eisenberg about our favorite parts of this compelling read.

Make It Better: “The Point Is” tackles a big, heavy topic, but the book itself is not heavy and I really appreciated your humor throughout. (I’m still chortling at how you refer to Freud as “my good Sigmeister.”) You address the issues that come with saying the meaning of life is to be happy, but how important do you find humor in the scheme of life?

Lee Eisenberg: Well, look no further than Woody Allen, whose greatest wisecracks have something to do with life’s most challenging or disturbing questions. One of my favorites, which I quote in the book: “Can we actually ‘know’ the universe? My God, it’s hard enough finding your way around in Chinatown.” And I love the story he told years ago, about how he was kicked out of college because he cheated on his metaphysics final: “I looked into the soul of the soul of the kid sitting next to me.”

The book is focused on the metaphorical “scribbler upstairs” that you say each person has in their brain, working 24/7 to construct their personal narrative. I’m wondering what you think of the editing that role requires. So many day-to-day experiences and even bigger memories do not get included in the story. Do you think the writer generally does a good job with what he/she edits out? Is it more incumbent on us to signal to our writer what’s important?

It’s fascinating how we retain certain memories, discard others, “rewrite” some so we can use them to build what we think of as our “life story.” Writing the book gave me the chance to go back through my own memories and how I’d altered some of them to fit the narrative. I was particularly interested in how, for example, I’d forgotten certain details of the evening our daughter was born. I’d all but forgotten about a lovely, gentle midwife who helped deliver our daughter in a London hospital. What brought it back was a journal I’d kept at the time, which is also something I’d forgotten about until I found it preserved on a hard drive.

Keeping a diary is one way to keep meaningful ideas and insights from vanishing from your life story. Why is that so important? Doing my research, I came across a lot of fascinating studies that indicate how we consistently under appreciate the significance of events and relationships when they occur. It’s only later that we understand how meaningful those events really were. Keeping those memories alive in the pages of a diary can result in a greater appreciation for how meaningful your life has actually been.

You characterize the middle of anything as the “elbow” and it feels like this is where the story can go off the rails. What advice would you give to people approaching the elbow?

As in many written stories, many life stories tend to wobble in midlife. We wake up one day and have no clue as to where the story should go from there. Often there’s a tendency to want to turn back the clock, somehow reclaim the younger version of yourself. So we do a lot of dumb things that range from wearing jeans that are too skinny or even walk out on an important relationship or job. The advice I’d give is basically what Carl Jung, who himself had a major midlife crisis, advised us to do: the former you is gone — he or she can’t be reclaimed. The assignment going forward is to find the whole you, the true self that exists within.

You note that “technology giveth and taketh” and touch on its impact at a few different points in the book. What concerns you the most about how technology is impacting the way we make sense of life and write our stories?

Technology is great but it’s distracting, as we all know. It can divert our attention away from moments that would otherwise fire the imagination, reveal the beauty in nature, or whatever. And being wired 24/7 gets in the way of tranquility and personal interaction, which is why my wife and I keep saying that we should have a technology-free day at least once a week, and have so far failed miserably at it. Then there’s social media. Some people have said they don’t have a need to record their thoughts in a diary because they can just post them on Facebook. Wrong! There are certain things we’d rather not share, or can’t find the right words for. A diary entry doesn’t call out to be “liked.” Nor should it.

Renting a home that was near a cemetery seems to have been a catalyst for writing this book, but you also say you’d “done a bit of spade work on the subject of death prior to arriving there.” Was renting that home in that particular location a turning point? Do you think you would have written it had you rented elsewhere?

It would certainly have been a different book had I not jogged through that graveyard every morning. It was the first time in my life I’d spent time in a cemetery without some grim reason to be there. Reading the inscriptions on the stones, reflecting on the various objects that loved ones had placed there, made me realize that there were more than just bones buried beneath the ground. There were stories: love stories, tales of valor, adventure stories, family sagas, etc. That became an important theme in the book and gave me a lot of running room, no pun intended.

It was fun to read the many Chicago and Evanston references in the book. How has Chicago as a setting influenced the portion of your story set here?

Yes, Chicagoland plays an important role in several sections of the book. Such as the day my wife and I attended the first-ever “Death Cafe” in Evanston. The Death Cafe has become a global phenomenon. You get together with a bunch of strangers and talk openly, over coffee and chocolate chip cookies, about how you feel about you-know-what. And it’s not the slightest bit depressing. It’s actually refreshing and therapeutic, if you can believe it. A great thinker once said that to fully appreciate life we must “deprive death of its strangeness.” Well, a few hours at a Death Cafe can help do that.

Another important local setting is the Newberry Library, where I wrote certain sections of the book. It also gave me the opportunity to retell how the library’s benefactor, Walter Newberry, died while on a European journey and how his body was shipped back to the States preserved in a rum casket.

The book addresses how the trajectory of one’s life matters. In all of your research and interviews, have some generally successful ways of nudging that trajectory in an upward direction emerged?

It’s never too late in life to try and move your story in the right direction, even if you feel stymied in your career or your relationship feels a little, uh, stale. There are plenty of ways to at least try. For many people, it calls for indulging their creative channel — writing, painting, making music, pursuing any sort of leisure-time passion. Another way is to give back to a cause you believe in — community, church, charity, etc. Still another is to fix or at least come clean about a relationship that was once important but, for whatever reason, didn’t end the right way.

You use many wonderful quotes by great thinkers throughout “The Point Is.” Do you have a favorite?

I guess I’d point to something that comes right at the end of the book — a few lines taken from one of Anaïs Nin’s diaries. Nin was responding to a question she’d been asked about why writers write. Her answer, in part: “We write to heighten our own awareness of life, we write to lure and enchant and console others, we write to serenade our lovers. We write to taste life twice, in the moment, and in retrospection.” I close the book by asking readers to read those lines one more time, substituting the word “live” for the word “write.” When you do that, you’re suddenly staring at beautiful reasons to be alive.

More from Make It Better: