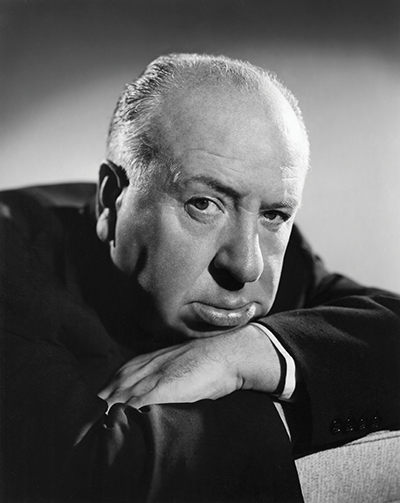

Alfred Hitchcock’s daughter Patricia once told me an amazing behind-the-scenes story about one of the films the Master of Suspense shot in the North Bay.

Alfred Hitchcock’s daughter Patricia once told me an amazing behind-the-scenes story about one of the films the Master of Suspense shot in the North Bay.

The movie was Shadow of a Doubt, the 1943 suspense thriller starring Joseph Cotten and Teresa Wright. Shot almost entirely in Santa Rosa, Shadow was Hitchcock’s first film to use North Bay locations. Fifty years after the film came out, Patricia Hitchcock was a guest on Hollywood Calling with Jan Wahl, an AM radio show I worked on in the early 1990s. I told Patricia I had just watched the movie for the first time, and it had shot up to near the top of my list of favorite Hitchcock films.

Patricia smiled and told me that during Shadow of a Doubt’s preproduction, her father came to Santa Rosa looking for locations, including a house for Wright’s character’s family to live in. Hitchcock sent scouts driving around Santa Rosa seeking a very particular kind of house: a solid home exhibiting some wear and tear. The team found the perfect place — a Victorian with cracked, faded paint and an overgrown, weed-encrusted yard. Hitchcock loved the photographs the scouts sent, and the homeowners heartily agreed to let Shadow of a Doubt use their place for filming.

As Hitchcock finished work on another movie, several months passed. When his production crew arrived in Santa Rosa to begin filming Shadow of a Doubt, they came back to the house they’d picked as a key location. There was one problem.

“The homeowners were so excited that their house was going to be featured in a Hollywood movie,” Patricia recalled, “they had the place painted and the lawn mowed and weeded.”

Hitchcock had his set design team ugly up the house in time for production — and repaint it again afterward — and the Victorian on McDonald Avenue became part of movie history. (The street isn’t a one-trick pony, cinematically: The house across the street was used for a 1991 TV remake of Shadow of a Doubt, and another place down the block was used in the 1996 slasher-hit Scream.)

Seventy-five years after its release, Shadow of a Doubt holds up marvelously as a still-disturbing film noir — Cotten’s sociopathic “Uncle Charlie” was inspired by real-life serial killer Earle Leonard Nelson — as well as one of the great North Bay movies of its time. Although it was not a box-office success on initial release, Hitchcock has often referred to it as his best film. According to Turner Classic Movies, he saw it as “one of those rare occasions where you could combine character with suspense. Usually in a suspense story there isn’t time to develop character.” He has also been quoted as saying that for him the thrill of the movie lay in the idea of bringing an evil menace to a small town.

From Hollywood to Northern California

Thirty years later, Hitchcock would revisit that theme of small-town menace in another North Bay work, The Birds. Filming in Northern California led him to fall in love with the region. The British-born filmmaker started in the silent era, directing more than 20 films in England — notably The 39 Steps, The Lady Vanishes and the Peter Lorre version of The Man Who Knew Too Much — before moving to Hollywood to direct the 1940 Oscar-winner Rebecca. Shooting that movie in coastal Monterey County, Hitchcock was so taken with the landscape that he wanted to buy property in the area. That fall he purchased a 200-acre winery in Scotts Valley, a spectacular setting where he entertained the likes of Cary Grant, Ingrid Bergman, James Stewart, Kim Novak, and Princess Grace and Prince Rainier of Monaco.

The winery provided a frequent northern respite for the Hitchcock family during his wildly productive Hollywood career. While he often shot in real locations (the Jefferson Memorial in Strangers on a Train, the French Riviera in To Catch a Thief, London and Marrakech in the James Stewart version of The Man Who Knew Too Much), he used the controlled environments of Hollywood soundstages for masterworks such as Rope and Rear Window.

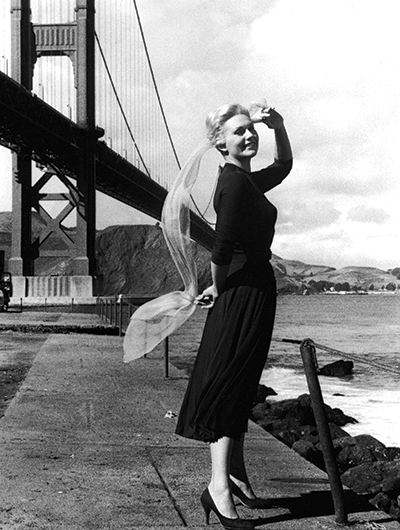

Fifteen years after Strangers on a Train, Hitchcock returned to the Bay Area to film scenes for what many critics consider his greatest achievement, Vertigo. Certainly one of the cinema’s great documents of midcentury San Francisco, Vertigo follows James Stewart as an afraid-of-heights detective chasing hauntingly beautiful Kim Novak around spectacular Northern California locations.

Marin County is on beautiful display in the background of one of the film’s most dramatic scenes, when Novak attempts to drown herself in the bay near the base of the Golden Gate Bridge. However, another scene, in which Stewart and Novak walk under giant redwoods, was filmed not in Mill Valley’s Muir Woods as widely assumed (and as the Internet Movie Database suggests) but in Big Basin State Park south of San Francisco, not far from Hitchcock’s winery.

Like Shadow of a Doubt, Vertigo was a rare box office disappointment for Hitchcock. But he followed it with two box-office smashes: North By Northwest and Psycho. The latter, filmed on studio sets with a television-size budget of less than one million dollars, became Hitchcock’s most successful money earner. After Psycho, he returned to the North Bay to make his last true masterpiece, The Birds.

Bodega and the Birds

The Birds is based on a 1952 novelette by Daphne du Maurier, author of Rebecca and Jamaica Inn — both also made into Hitchcock movies. The book is set in du Maurier’s hometown of Cornwall, England, but Hitchcock set his sights on Bodega Bay as the film’s location. The movie, a unique horror-fantasy, depicts an apocalyptic nature-versus-human onslaught as flocks of birds attack Bodega Bay’s residents — including young children — without mercy.

Hitchcock, who made 13 films and the Alfred Hitchcock Presents television series (1955–1965), worked for nearly three years on The Birds. The film employed special effects — mostly regarding the titular villains — that were by far the most advanced of any seen in Hitchcock’s canon. But the director also did extensive preproduction work in Bodega Bay. “In order to get the detail right, I had every inhabitant of Bodega Bay — man, woman, and child — photographed for the costume department,” he told Cinema magazine, according to Jeff Kraft and Aaron Leventhal’s book Footsteps in the Fog: Alfred Hitchcock’s San Francisco.

The beauty of watching The Birds today is that unlike locations in many films of the early 1960s, many of its settings look exactly the same today. The film’s star, Tippi Hedren, says she makes an annual pilgrimage to Bodega Bay. “I go every year on Labor Day and stay for several days to sign autographs and talk to everyone,” said Hedren, whom Hitchcock first spotted in a diet drink commercial. “It’s really amazing that everything is still there.”

I made Hedren’s acquaintance in 2003 during a weekend celebration of The Birds’ 50th anniversary. One of its highlights was a visit to the Potter Schoolhouse in the town of Bodega. The 150-year-old building is now a private residence, but a classroom from the former school has been maintained to appear just as it did in the movie. The play structure outside — site of the film’s initial spectacular, horrifying bird attack — has been disassembled and donated to another school.

The Tides Wharf Restaurant, featured in several scenes, was rebuilt in the 1990s and is now part of the Inn at the Tides. Across Highway One, the Sonoma Coast Visitors Center sells a guidebook packed with information about The Birds.

Hedren, who famously had a falling-out with Hitchcock in 1964 while making Marnie (filmed largely in San Jose), has nothing but happy recollections of filming The Birds.

“If it wasn’t for The Birds, I wouldn’t be doing everything that I’m doing now,” she noted. Besides acting, that includes running the Shambala Preserve, a sanctuary for large cats and elephants that have been mistreated. Most memorably, the movie introduced her to a place where she’d be welcomed her entire adult life. “The first time I went there was to film The Birds, and I just love to go back and visit and see the locations,” she said. “It really is a wonderful place, filled with wonderful memories.”

This article originally appeared in Marin Magazine.