From its gleaming white terra cotta façade to its enduring clock tower presence on Michigan Avenue, the Wrigley Building has long stood as a symbol of Chicago. But in the new book The Wrigley Building: The Making of an Icon, four of the city’s foremost historians and creatives reveal that this architectural marvel is far more than a postcard image. It’s a living archive of 20th-century ambition, artistry, and innovation.

Blending over 400 rare images with untold stories of designers, dreamers, and cultural revolutionaries, this definitive volume traces how the Wrigley Building became a hub for everything from modernist art and jazz to groundbreaking advertising and broadcast media. The book is the result of a collaborative effort by Robert Sharoff, a journalist known for unearthing hidden histories of architecture and culture; William Zbaren, a celebrated photographer whose access to the building yielded never-before-seen images; Tim Samuelson, the city’s first official Cultural Historian and a passionate chronicler of Chicago’s creative life; and John Vinci, an acclaimed architect and preservationist whose work has shaped both the city’s skyline and its architectural legacy. Together, they bring a multidisciplinary lens to one of Chicago’s most storied structures.

In the following excerpt, readers are transported to the 1920s and introduced to one of the building’s most fascinating tenants: the Arts Club of Chicago. Under the direction of Rue Winterbotham Carpenter — socialite, designer, and champion of modernism — the club transformed its Wrigley Building headquarters into a cultural proving ground for artists like Picasso, Brancusi, and Matisse. Today, it remains among Chicago’s most prestigious private clubs.

Chapter 20: Her Social Life Was Impressive

When the Arts Club of Chicago moved into a second-floor space in the north tower of the Wrigley Building in 1924, it was looking for a fresh start.

The club, which had been founded in 1916 with the aim of advancing the cause of modern art in the city, had had two previous homes, both on Michigan Avenue south of the river. By 1924, with the opening of the Boulevard Link, it was clear that the city’s center of gravity had shifted. If Michigan Avenue was Chicago’s Champs-Élysées, its Left Bank was Towertown, the bohemian neighborhood north of the Wrigley Building where artists and stylish young people were starting to congregate. This and the fact that the Wrigley was the building of the moment made it an ideal location for the club.

The club had about one hundred members, including a dozen or so architects. Such well-known names as Hubert Burnham (son of Daniel Burnham), John Holabird of Holabird & Root, Philip Brooks Maher, and David Adler were members. (Beersman does not appear to have been a member.)

The club’s president was Rue Winterbotham Carpenter, a premier mover and shaker in 1920s Chicago. Born in 1876 to a wealthy manufacturing family, Carpenter was a hyphenate before the term was invented. In addition to managing the day-to-day activities of the Arts Club, she parlayed her extensive social connections into a successful career as an interior designer. The author and Chicago social historian Arthur Meeker Jr. described her as “the most brilliant woman I have ever known” and “one of the two most important decorators of the early 1900s in America.” (The other was Elsie de Wolfe.)

Her social life was impressive and included parties in Paris with those Lost Generation avatars Gerald and Sara Murphy and their retinue of artists and writers. For example, in 1923, Carpenter and her husband, modernist composer John Alden Carpenter, attended what is sometimes called the party of the decade — an all-night extravaganza staged by the Murphys on a barge in the Seine to celebrate the opening of Igor Stravinsky’s Les Noces ballet. Other guests included Pablo Picasso, Tristan Tzara, Jean Cocteau, and Sergei Diaghilev. The Carpenters were also known to vacation in Venice with Cole Porter and his wife, Linda. Cole once gave the Carpenters’ daughter, Ginny, a puppy.

In short, she was ideally placed to lead what became one of the most important showcases for modern art and design in America during her decade at the helm.

The club’s first space in the Wrigley was co-designed by Carpenter and the architect Arthur Heun, and it seems safe to assume that Heun — a designer of lush Beaux-Arts estates on the North Shore — handled the more mechanical aspects while Carpenter supplied the vision. Indeed, photos of the club reveal that it shared many features with the Casino Club, which Carpenter decorated later and which is generally regarded as her masterpiece. That and the nearby Fortnightly Club are her only remaining interiors.

Carpenter, said Meeker, was “sympathetic to the Directoire and Empire periods” and “understood how to adapt them to present day American needs.” She liked Biedermeier furniture, taffeta curtains, Aubusson rugs, and broad-striped wallpapers, many of which would be utilized at the Arts Club.

“There are lovely vistas, shapely galleries, spacious lounges, an attractive dining room, quaint little oddly shaped reception and committee rooms and ample dressing rooms,” noted the Chicago Tribune. “It will undoubtedly become a favorite rendezvous for luncheon and tea parties. Situated as it is in the new Wrigley Building, it will be much more accessible than was the old club on South Michigan Avenue.”

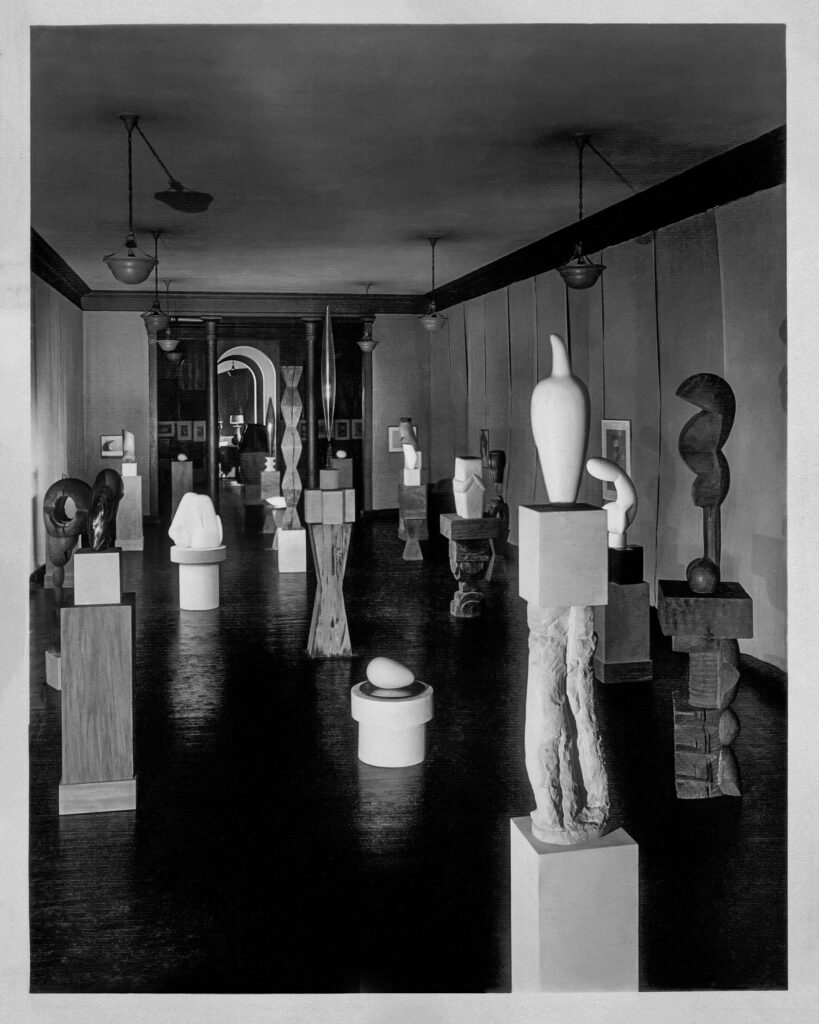

Over the next seven years, Carpenter — along with Alice Roullier, chair of the club’s exhibition committee — staged groundbreaking shows and events. The names alone tell the story: Picasso, Braque, Brancusi, Matisse, Léger, Chagall, Man Ray, Noguchi, Modigliani, Duchamp, Mirò. All were featured in solo exhibitions at a time when they were effectively barred from the Art Institute of Chicago and other mainstream museums.

One of the most spectacular shows Carpenter oversaw was the Brancusi exhibition, which was curated by Marcel Duchamp and from which the club acquired, for a mere 200 dollars, Golden Bird, a sculpture that remained a highlight of the club’s permanent collection for sixty-odd years. (In 1990, it was sold to the Art Institute of Chicago for 12 million dollars to fund construction of the club’s current home on Ontario Street.)

Carpenter — and the club — took an all-encompassing view of culture. In addition to the visual arts, the club regularly hosted lectures and performances by figures such as composers Aaron Copland and Sergei Prokofiev, pianist Arthur Rubinstein, dancer Martha Graham, poets Robert Frost and Archibald MacLeish, playwright Thornton Wilder, futurist Buckminster Fuller, and philosopher Bertrand Russell.

That all of this was taking place within an elevator ride of the reams of commercial art produced by the Wrigley Company is a contrast that both Carpenter and Wrigley would have appreciated. Wrigley understood that the Arts Club lent class to the building, and Carpenter was no stranger to commercialism. Indeed, she traded on her image as a social arbiter by appearing in ads for household products.

In 1931, at the age of fifty-five and at the height of her success, Carpenter died in a doctor’s office where she had gone to be treated for a cold. The cause was a cerebral hemorrhage. She was succeeded by socialite Elizabeth “Bobsy” Goodspeed, who oversaw the 1936 relocation of the club from the north tower of the Wrigley Building to a larger space on the second and third floors of the south tower. (By then the club had just under seven hundred members.)

The new spaces were designed by a triumvirate of architects — Arthur Heun, Samuel Marx, and Gilmer V. Black — but remained indebted to Carpenter’s vision. Goodspeed was also credited, but what she did is not clear. She had no history as an interior designer but evidently was involved in the bold, saturated color choices.

Rather than a stately progression of Beaux-Arts galleries, the new quarters were a collection of variously sized rooms grouped around a central core. Overall, they preserved the Directoire feeling of the earlier spaces but injected it with more vivid colors and luxurious materials. For example, the entrance hall had deep blue walls and a pale pink ceiling, while the octagonal inner hall had Pompeian red walls and a pale gray ceiling. Both rooms also had black terrazzo marble floors.

The Wrigley Building: The Making of an Icon is available in bookstores and online.