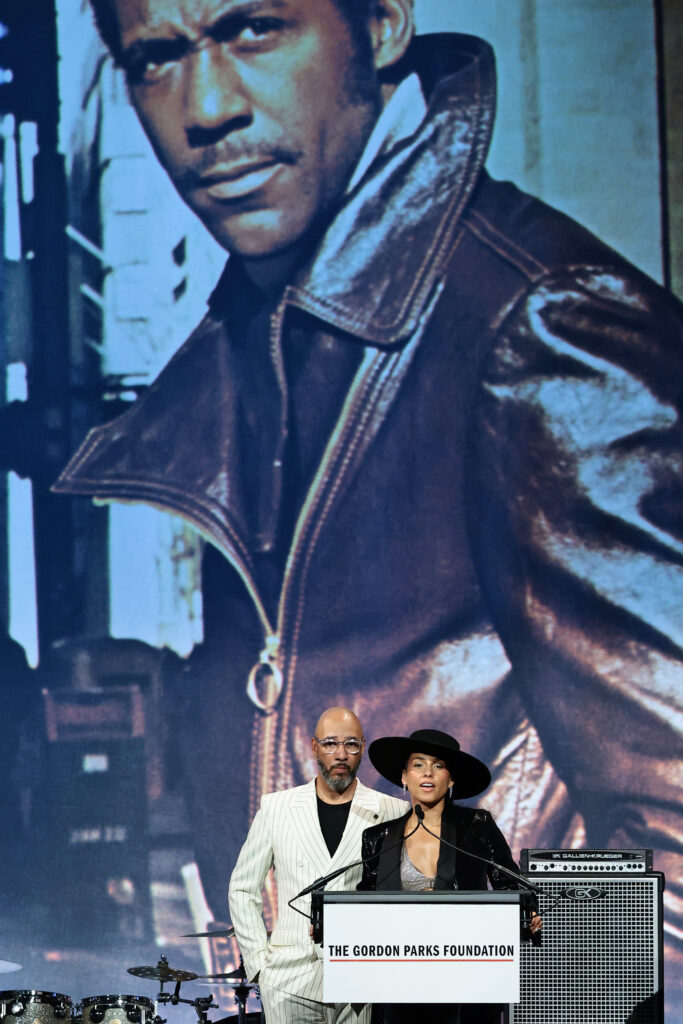

Over the past two Sundays, Alicia Keys at in her GRAMMY acceptance speech for the Dr. Dre Global Impact Award and Kendrick Lamar through his Super Bowl halftime performance delivered powerful messages about the power of art to inspire future generations and advance social justice. What do the two artists have in common? They’ve both been deeply and vocally inspired by the art and activism of Gordon Parks, participating in meaningful collaborations with the Gordon Parks Foundation to honor the late photographer’s legacy.

The Gordon Parks Foundation, co-founded in 2006 by the late photographer’s friend and former Life magazine editor Philip B. Kunhardt, Jr., supports and creates artistic and educational initiatives that advance Gordon Parks’ legacy and, through the Gordon Parks Arts and Social Justice Fund, empower the next generation of artists committed to social justice. The Foundation collaborates with and is supported by contemporary artists, musicians, and cultural leaders — including Lamar, Keys, Swizz Beatz, and Spike Lee — who help introduce and expand Parks’ legacy to new audiences.

The Foundation has engaged in high-profile collaborations and received strong backing from influential supporters. Kendrick Lamar’s music video ELEMENT., from his Pulitzer Prize-winning album DAMN., pays direct homage to Parks, reinterpreting some of his most striking images of Black life in America. The Foundation highlighted this artistic dialogue with ELEMENT., an exhibition pairing Parks’ photographs with stills from the video.

Alicia Keys and Swizz Beatz, longtime champions of Parks’ work, hold the largest private collection of his photographs through the Dean Collection. Their support has included co-chairing the Foundation’s annual gala and collaborating on exhibitions like Gordon Parks: Selections from the Dean Collection, which debuted at Harvard University in 2019.

The Foundation’s archives preserve Parks’ photographs, negatives, contact sheets, and publications, while its exhibition space in Pleasantville, New York, presents his work alongside that of other artists. Through fellowships, grants, and curated exhibitions, the Foundation ensures that Parks’ legacy continues to inspire new generations dedicated to art and social change.

A Self-Made Artist Who Transformed American Photography

Born in 1912, Gordon Parks’ artistic ability emerged early in his hometown of Fort Scott, Kansas. By age six, he had learned to play the piano by ear. As a teenager, he moved to Minnesota, where a sister lived. He earned money playing the piano at a brothel until one Saturday night a man fell a few feet from his piano with a knife lodged in his chest. The customers, prostitutes, the pimps, and Parks fled. This was not the first time the young Parks had been exposed to violence: he had witnessed two drunken women knifing each other to death in front of a pool hall and lost many friends to gun violence.

In 1929, a job as a busboy at the prestigious Minnesota Club opened up a new world for him. Borrowed books from the club library became his textbooks. He continued to expand his world as a waiter on a train, the North Coast Limited, in 1937 and 1938. On one journey, he saw a photo essay about migrant workers in a magazine that a passenger had left behind and could not forget the images of the dispossessed roaming the country or the names of the photographers who captured them on film — Arthur Rothstein, Russell Lee, Carl Mydans, Walker Evans, Ben Shahn, John Vachon, Jack Delano, and Dorothea Lange. Overcoming prejudice and the not-so-insignificant fact that he didn’t own a camera at the time, let alone know how to use one, by 1942, he had joined the ranks of this esteemed group as a photographer himself for the Farm Security Administration.

Earlier, for his first professional photo assignment of fashions for a department store, Parks double-exposed all but one image by mistake; it was the first time he had used a Speed Graphic camera, and he had not turned the 4 x 5-inch film holder around. He took the one photograph that was not double-exposed to Madeline Murphy, the store owner’s wife. “Would they all have been this nice?” she asked. “Of course,” he replied, “It was the worst one.” They did it again, this time successfully. Boxing great Joe Louis’ wife Marva came to town, saw Parks’ work in the window of the store, and encouraged him to come to Chicago. After seeing some documentary work that Parks had done on the city’s South Side, Jack Delano of the Farm Security Administration encouraged Parks to join the FSA, which he did in 1942.

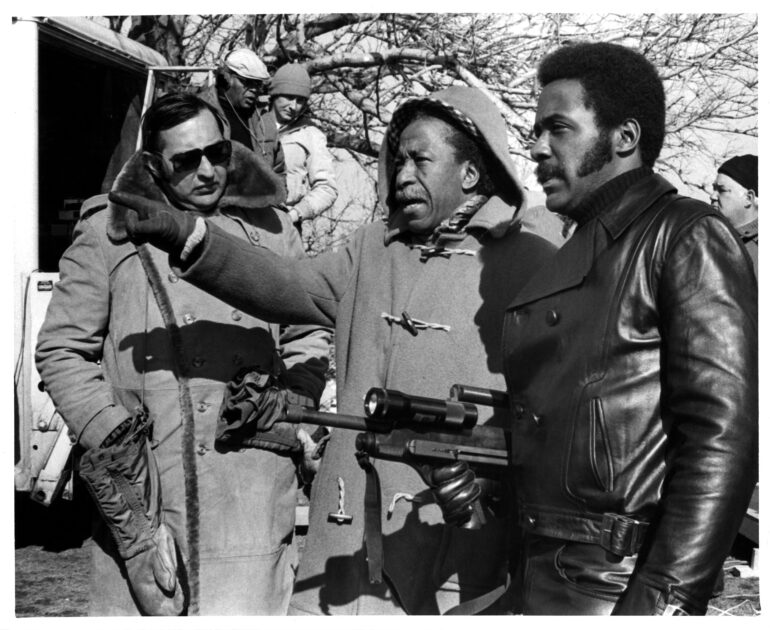

In 1948, he began a career with Life magazine. After leaving Life, Parks began to concentrate on books, film, music, and more abstract color photographic work.

Gordon Parks in His Own Words: Reflections on Art, Race, and Storytelling

The following excerpts are from my 1998 interview with Gordon Parks, originally published in Faces of the Twentieth Century: Master Photographers and Their Work (Abbeville Press). In his Manhattan apartment, overlooking the United Nations, I captured a portrait of the legendary photographer, writer, musician, and filmmaker — whose groundbreaking film work included Shaft, a personal favorite of mine. Inspired by his autobiography, Voices in the Mirror, our conversation traced his extraordinary journey from self-taught artist to one of the most influential photographers of the 20th century. Parks, who passed away in 2006, remains a towering figure in photography, one who used his lens to challenge injustice and illuminate the human experience.

Words by Gordon Parks:

“My interest in photography began while I was working on a train, the North Coast Limited, as a waiter in 1937-38. Up until then, I had never shot a photograph before in my life. The thing that probably set me off was watching a newsreel in a movie house during a stopover in Chicago of the American gunboat Panay being bombarded in the Yangtze River by the Japanese and watching it sink. The guy who filmed it, Norman Alley, jumped onstage to a standing ovation after the presentation. In the first place, I thought his part was rather glamorous, which struck an inner chord.

Possibly the most persuasive influence was the FSA photographs that I saw of Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, Arthur Rothstein, Jack Delano, Carl Mydans, and John Vacon. I suppose it touched me that if they could reach out and make the public aware of how terrible this poverty was to the people who were no foot all over the land – farmers losing their homes and so on – that I could make the same stroke against racism that they were making against poverty.

At that time, the idea struck, but it didn’t take over. It influenced me. My mind was all over the place. I was also seeing for the first time fashion photographs in these glamorous magazines that rich people were leaving on the train…beautiful women being photographed in Paris and London. I was this little kid from Kansas. You don’t have time to think about the impossibility of it. The fact that you don’t even have a camera. The fact that you couldn’t afford to buy the camera. The fact that I probably couldn’t use it after buying it. The hell with that. You let your imagination carry you.

I’m a gambler. I learned you can’t go any farther down than the bottom; everything else is up – take a gamble. I bought a Voightlander Brilliant for $7.50 in a pawnshop in Seattle, Washington. The train had stopped there three days after I saw the newsreel in Chicago. I didn’t know how to load it, neither did the guy in the pawnshop. But he did have some film on a shelf, and there was a customer in the shop at the time who was nice enough to say, “I’ll load it for you.” I have a tendency to think he was some very well-known photographer from out West.”

“Jack Delano of the Farm Security Administration, after seeing some of the work I had done on the south side of Chicago, encouraged me to come to the FSA, which I did in 1942. The first day I was in Washington, Roy Stryker sent me out. He had asked me, “What do you know about Washington?” “Well, it’s the capital of the United States. It’s where the President lives….” I continued with mundane answers like that. So he gave me this assignment that seemed very strange. He told me, “Put your camera down and go buy yourself a topcoat at Julius Garfinckel’s Department Store, go across to the restaurant to get some food, and go to the theater and see a movie and come back to the office.”

In each of these places, I was refused in one way or another. Outright at the theater. Subtly at Julius Garfinckel’s. They just couldn’t find my side topcoat or didn’t try. At the restaurant, they refused me at the counter. I faced all that in one afternoon. Stryker had obviously given me the assignment to wake me up to the reality of the place. I suppose that in a strange sort of way, racism in Washington, D.C., struck me harder than what I had suffered from as a child in Kansas.

I took Stryker’s suggestion to talk to other black people who had spent their lives in Washington. I struck up a conversation with a black charwoman who was mopping the floor in the building. In the next hour, she guided me through a lifetime of drudgery and despair. I asked her if I could photograph her. I placed her in front of an American flag with a mop in one hand and a broom in the other. I think this first photograph that I made for the Farm Security Administration became one of the most powerful photographs in my repertoire.

One thing my mother taught me was that you don’t use your blackness as a crutch for failure. ‘If a white boy can do it, you can do it better. Don’t come in here telling me you didn’t do this and you didn’t do that because you’re black and they didn’t give you a chance. Go around them. There is always a way to go around them. Show them. Prove it to them. Make them come to you.’ Now, where this this woman got this philosophy fro,m I don’t know. I don’t know if she even finished high school.

I was the youngest of fifteen children. She died when I was fourteen. She knew she was dying and tried to pour all her knowledge into me in a very short time… whereas she had a lifetime to give it to the others…certainly pouring in the love, a way to reason things out, a way to balance things out, a way to escape racism. I suppose as a kid I had been brought up with it in Fort Scott, Kansas. I couldn’t even take my girlfriend to the corner drugstore and have a soda. It was for whites only. The grade school was segregated. The only reason they possibly didn’t segregate the high school was that the town fathers couldn’t raise enough money to build another high school. But we were told by our class advisor that we shouldn’t worry about going to college. It didn’t matter if we even finished high school because we were going to end up as porters and maids. That’s the sort of atmosphere we were spawned in.

Now, I’m going to television and radio stations, stores, and banks and seeing black people and other minorities doing things that they never would have dreamt of doing when I was a young man. I’ve seen tremendous racial change. It’s extremely difficult to dispute that. Yet, there still are these great depressed areas – Harlem, Watts, the south side of Chicago – which seem to be growing despite the changes. It’s decadent. The south side of Chicago that I knew is not getting any better. It’s gotten worse—the same thing in Harlem. So, in one way I see enlightenment and change. In another way, I see some kid up there who cannot appreciate the distance that I have come. He is still poor. He’s still cold. He’s still hungry, and he’s still discriminated against. He has no mother or father as I had to encourage me. He’s lost. You can very easily displace the word “progress.”

I gave some advice to a young black man who wanted to be a photographer. He asked, “How the hell did you do it way back then when there was nobody to help you? You went to Vogue, you went to Life, you were the first black director in Hollywood…” “You really want to know how I did it? By forgetting that I was African American. I was just an individual out to do a job. I could not be hampered by racism and what racism does to people. I refused to accept it. I ignored it. I walked around it.

As my dad used to say, ‘Waltz around it and foxtrot on their backs [laughing]. If you are going to let bigotry destroy you, the people who have set it all up will be happy because this is what they wanted to happen. If somebody sees your work and they don’t hire you, don’t let race become an excuse for your failure, where actually it wasn’t for that reason. All right. How many white boys would have loved to have worked with Life magazine when I began there in 1948? Millions would have liked to have been Life photographers. That was the goal. How are I even dream?”

How to Help

Donate to Gordon Parks Arts and Social Justice Fund to carry on Park’s legacy and support generations of artists fighting for social justice. The foundation’s funds support public programs, exhibitions, annual scholarships, and fellowships.

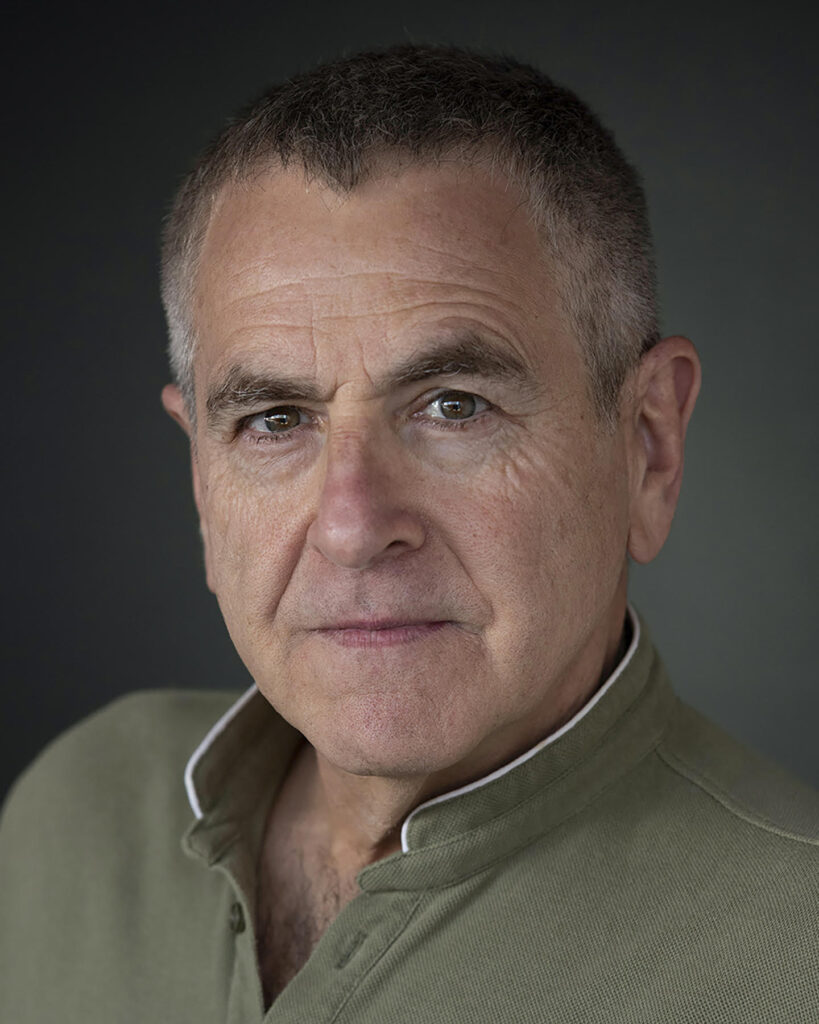

Assignments have taken award-winning photographer and Make It Better Foundation Director of Photography Mark Edward Harris to more than 100 countries on all seven continents. His books include Faces of the Twentieth Century: Master Photographers and Their Work, The Way of the Japanese Bath, Wanderlust, North Korea, South Korea, Inside Iran, The Travel Photo Essay: Describing A Journey Through Images and his latest, The People of the Forest — a book about orangutans. He proudly supports the Center for Great Apes, the Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation, and the Search Dog Foundation. You can find him on Instagram or at his website.