Journalist. Author. Beauty queen. Prisoner. Human rights advocate. All of these words describe Roxana Saberi, who was held in Iran’s most notorious prison for 100 days in 2009.

The Iranian authorities charged her with spying and sentenced her to 8 years, before deciding to release her.

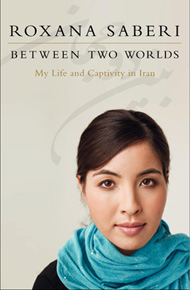

An alumna of Northwestern’s graduate journalism program, Saberi recently returned to the North Shore to speak about her experience, as part of her book tour for “Between Two Worlds: My Life and Captivity in Iran” and before flying to New York City for the premiere of “No One Know About Persian Cats,” the film she co-wrote about Iran’s underground music scene.

She will be living here this summer, teaching in Northwestern’s National High School Institute (Cherubs), a summer program for outstanding high school students.

Her book is a dark portrait of Iran’s government and its treatment of political prisoners, and will inspire a deep appreciation for freedom and democracy in anyone who reads it. Her strength and grace was a stark contrast to the conditions she described.

MIB: What do you hope people will take away from your book?

RS: What happens on the other side of the world is important. What happens in Iran and in that region is important for the world.

When there’s pain in one part of the world, it’s felt in other parts. When there’s goodness, it can spread. What’s important is the efforts of ordinary people to bring attention to injustices—it’s not just the job of governments. People can pressure governments to change.

MIB: So, what can we in the U.S. do to help people whose human rights are being violated in places like Iran?

MIB: So, what can we in the U.S. do to help people whose human rights are being violated in places like Iran?

RS: You can sign a petition to free writers and journalists imprisoned in Iran at oursocietywillbeafreesociety.org. You can write letters to your representatives in Congress or the Iranian mission to the U.N. You can support Reporters Without Borders.

MIB: Do people sometimes misunderstand what happened to you?

RS: Some people say, “Don’t these people [me and my fellow prisoners] know these things are risky?” But you can be imprisoned for anything there.

When I was in prison, I was sorry at first that I interviewed so many people. Later on, I thought, why should I feel sorry? I had a right. My cellmates were there for exercising basic human rights. I was there exercising my freedom of expression. I knew I might be questioned, but I didn’t expect that writing a book would land me in prison.

The political prisoners, or “prisoners of conscience,” knew they might be monitored. They take a calculated risk because their work is worth it. If people didn’t do things out of fear, there would be no student activists, no human rights campaigns, no journalists trying to share the truth, no members of NGOs working, teachers calling for better wages … There would be a lot more repression.

These [political prisoners/prisoners of conscience] are the hope for democracy. People ask, “Shouldn’t they have known better?” when the question should be, “Why are their rights being violated?”

Interested in Roxana’s story? Buy the book here .