“People protect what they love — and they love what they understand.” This simple message, shared by Dr. Jill Tiefenthaler, CEO of the National Geographic Society, captures the heart of The National Geographic Photo Ark, a groundbreaking project by National Geographic Explorer and award-winning photographer Joel Sartore.

The Photo Ark is more than just a visual archive — it’s a race against time to document every species living in the world’s zoos, aquariums, and wildlife sanctuaries and inspire action before it’s too late. Sartore hopes the intimate, striking portraits will connect people with wildlife in a way that sparks empathy and drives conservation.

“We know many animals will be going extinct, especially the smaller species,” Sartore says. “But we can lessen that by getting people to realize these animals are fabulous — and most of them are still here.” With more than 16,500 species photographed so far — and many more to go — this ambitious project is as much about documentation as it is about awakening a global sense of urgency.

During a recent conversation at the Executive’s Club of Chicago with Shedd Aquarium President and CEO Dr. Bridget Coughlin, named one of Chicago’s most powerful women by Better, Tiefenthaler emphasized National Geographic Society’s mission of “illuminating and protecting the wonder of the world,” highlighting how Sartore’s work embodies this goal by connecting people to wildlife through powerful imagery.

In this interview, Make It Better Foundation Director of Photography Mark Edward Harris speaks with Sartore about the journey behind the Photo Ark, the pressing challenges facing global biodiversity, and how this visual storytelling effort has evolved into a beacon of hope for conservation.

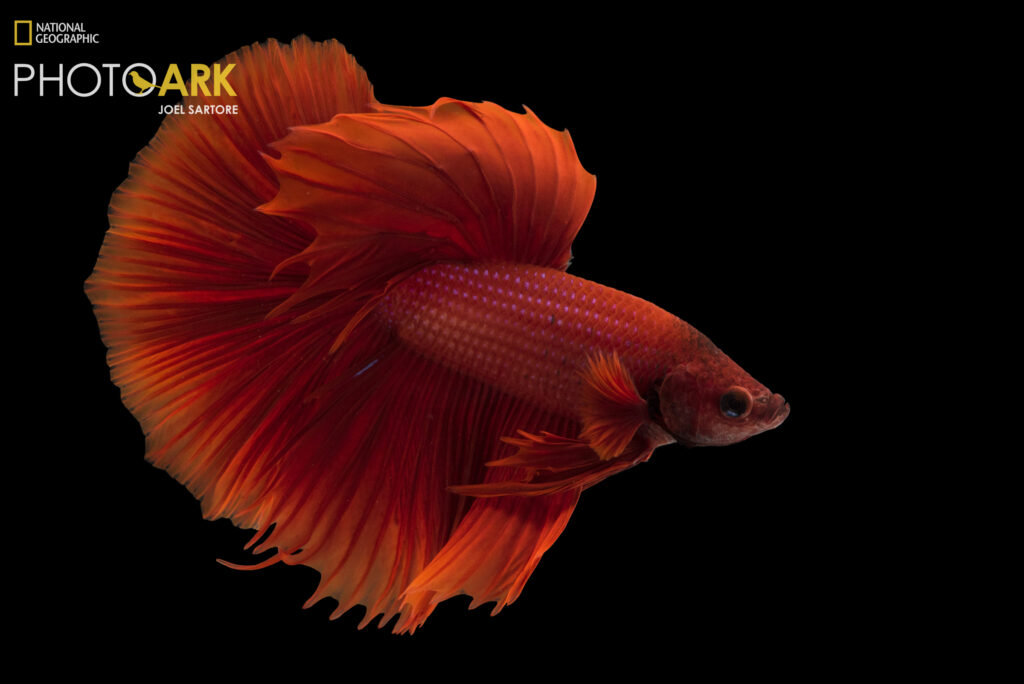

Sartore/ National Geographic Photo Ark

Mark Edward Harris: How many species have you photographed to date?

Joel Sartore: We’ve gotten 16,500 or so. The ultimate goal is to get every type of animal in human care around the world. It could be 25,000 species, but we don’t know because the farther we go, the more we find, and there are a lot of islands in the South Pacific that are going to lose their biodiversity when they flood due to rising sea levels, so there’s a race to get to those places. We have most, if not all, of the common animals in Western zoos and aquariums.

MEH: How much time do you spend on the road?

JS: I work on the Photo Ark every day, either researching or shooting. Shooting is probably a third of my time. I was just in China for a month, and before that in Peru and Chile. I take my oldest son Cole with me. He’s an excellent photo assistant and shoots some video as well.

MEH: It’s fascinating that you have everything from the largest of animals on the planet to the tiniest of insects in the Photo Ark. How do you keep track of everything?

JS: I keep a list of what we’ve photographed. We basically have six categories: Mammals and birds, reptiles and amphibians, fish and invertebrates. Insects are part of the invertebrate group. Spiders are arachnids, scorpions are arachnids. They’re not insects, so we lump them in with invertebrates. Invertebrates can be corals, sponges, sea anemones, jellyfish, or squid.

The web has really blossomed since we started which has been a big help. The Zootierliste, for instance, a website run out of Germany, is remarkable. They travel the world going to zoos and aquariums. So we’re able to keep up with this and document biodiversity with the goal of getting people to care and to think about our actions, to try to lessen our impact. We know many animals will be going extinct, especially the smaller species. But we can lessen that by getting people to realize these animals are fabulous, and most of them are still here, though their numbers are down significantly year after year.

MEH: All because of human actions?

JS: You bet. Climate change and pollution and habitat loss and pesticides and herbicides. We’re basically converting the world into a farm. We use a lot of chemicals on farms to keep insects at bay so we can grow our crops. I get that. I eat, too. But we need to set aside big tracts of intact habitat if we want to keep our climate stable. Like the Amazon, it doesn’t just provide us with oxygen and cool the world. It drives rainfall patterns on our side of the world. So if we cut down all the trees in the rainforest, we’re going to lose the ability to grow crops in many places where there’s good soil because the rains will quit coming or there’ll be too much rain. It’s to our advantage to preserve at least half the Earth’s biomass and half the Earth’s available terrestrial habitat. That’s a giant deal. But that’s very hard to get across.

MEH: Especially to a species that’s fighting with itself over politics, land, or even the price at the pump.

JS: The cost of everything. And I understand that’s our nature. Also, we prefer watching sports than hearing about insulating our homes or driving smaller cars or recycling. We’re creatures of comfort and we want to maintain that. But my job is to tell the story of all these animals around the world.

Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark

MEH: Trying to get people to care while there’s still time. What was the initial catalyst for the project?

JS: I was a National Geographic magazine photographer doing stories in the field for 17 years and then my wife Kathy got sick. She’s fine now, but she was sick for about a year, and I stayed home to take care of our kids, to be a dad for a change. During that year, I thought about the fact that most animals are not tigers or polar bears or gorillas. And most animals you could fit into the palm of your hand. They’re just not ever gonna get any ink. So I started thinking about ways to solve that if Kathy got better.

I started at the Lincoln Children’s Zoo in Nebraska, about a mile from my house. I went there on days my wife felt well and just photographed little animals on white and black backgrounds. I think a naked mole-rat was the first one. Then I would do little day trips and go to Omaha, which is an hour away, and work at their zoo, which is world-class with over 600 species. Then Kansas City and Des Moines. I would radiate out from Lincoln to Sioux Falls, Denver, Oklahoma City, Wichita, all these places where I could go to and get back from quickly.

MEH: Have you seen a lot of loss in species from those early days on the project until now?

JS: I have seen the decline of a lot of nature, fewer and fewer birds in the woods and fewer frogs singing, and a lot in the Americas because of chytrid fungus. The forests have gone silent in lots of places, but there are also things to celebrate. I don’t want to be too down, and I don’t get depressed. I meet environmental heroes all the time that have devoted their lives to saving a forest, a prairie, a coral reef or a specific species. So if they don’t give up, I’m not going to give up. It’s heartening to see people devoting their entire lives to aquatic invertebrates that they know the public would never think about.

We have turned things around in many cases. The California condor, the Mexican gray wolf, the whooping crane, the black-footed ferret, the Wyoming toad. These animals are not on the verge of extinction anymore because people cared and they got to work.

MEH: California condors and wolves we see as majestic but tadpole shrimp are hard to relate to. But then, of course, they’re part of the food chain, and there are animals that depend on them.

JS: Right, and we rely on them, too. Wolves are a big driver of ecotourism — money into the places that have them, like Yellowstone National Park. You take the wolf out of the wilderness, and it’s not really wilderness anymore. But beyond that, the smaller things do drive the ecosystems that we depend on for clean water, clean air, and good soil. The most obvious example of that is the loss of insects that pollinate our fruits and vegetables. We are going to be up against it if we keep going the way we are. It’s not my job to be political or to wag a finger at anybody. We just want to show animals looking good and talk about the good work that people are doing and hope that the public cares enough to pay attention.

Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark

MEH: Have any of the animals you’ve photographed in captivity ever attacked you?

JS: No, these animals that we photograph are born and raised in human care, and they’re around people all day long, and people provide them a home and food, so they’re calm. We’re not looking for any drama, and the keepers know which animals can tolerate the process and which can’t. We go at a measured approach, getting things done quickly and quietly. The smaller animals can’t see us when they’re in the photo tent. They just see the front of my lens.

We say we’re going to photograph every captive species in the world. That’s our goal. At least we’ll get most of them. But we also take advantage of animals in the wild if they can be in a controlled circumstance because that allows us to show more biodiversity.

For example, we work with biologists of the Tennessee Valley Authority that are sampling rivers and streams. We document different mussel species and stream fish, little bitty guys that they catch that we photograph before they release them. We’ll go out with bird banders in Hudson, Wisconsin. There’s an annual bird banding for little warblers that migrate through so they can learn about population trends. So we’ll go there, and before the birds are released, we’ll put them into my tent on site, and then we’ll open the tent up, and they just fly off once we’re done photographing them.

MEH: How is The Photo Ark Species Impact Initiative impacting your efforts?

JS: The initiative continues to help save species. We’ve just completed the second year. The first year was to save the Pine Rocklands ecosystem. A big chunk of it is outside the Everglades. They have an entire suite of plants there that are endemic as well as insects like the Bartram’s scrub-hairstreak butterfly and the Miami tiger beetles. But they have a lot of invasive plant species that have to be cleared out to keep that Pine Rocklands area open enough so that the animals and plants that are native there will continue to use it. Native land and tree snails in Hawaii, mainly on Oahu, which are being run to extinction by an invasive snail called the rosy wolf snail, and also by chameleons and other introduced predators, were the focus in 2024. Fences with little flanges on the sides of the walls that invasive snails can’t get around were built. Conservators are reintroducing several native snail species to each “exclosure” to breed and thrive. They call them “exclosures” because they keep predators out.

MEH: Sometimes invasive species are introduced accidentally and sometimes on purpose. On the Japanese island of Amami, the mongoose was introduced to control the highly venomous habu snake, but they’re devastating to endangered species there, including the Amami rabbit. I saw mongoose traps all over the island.

JS: We’re shaking the snowball up globally and mixing all these species. There are a lot of consequences to that. As North America gets warmer, fire ants are marching their way north and are devastating to nesting birds. They climb trees as soon as the egg cracks or pips, and the ants go inside and eat the chick.

MEH: What can we do?

JS: People can go to my website, where there’s a list of things we can all do to help save the planet, starting right at home by planting a pollinator garden and reducing or eliminating the chemicals we’re putting on our lawns. There are a lot of benefits to our own health and well-being for thinking a little more about nature. Nature doesn’t need us, but we need it.

How can you get people to care about all species? On our bare background, the mouse is as big and important as an elephant. They’re reproduced all the same size. So, the tiger and the tiger beetle are equal. That’s a big help because some of these animals are the size of a sunflower seed.

We humans couldn’t live without ants, for example. They aerate the soil, they pollinate plants. We’re busy killing off a lot of the insects on most golf courses and farm fields with chemicals. If you like birds, you better like insects because birds feed their chicks insects. Without insects, down go the bird numbers. It’s all tied together.

The oceans are too hot from climate change, so the corals die, and the corals are responsible for a huge percentage of life in the oceans. They’re the nursery for many forms of fish and crustaceans. So, all these things are tied to us. Food doesn’t really come from the grocery store; it comes from nature, and we have to have nature intact to live. Photo Ark is designed to get people to come into the tent of conservation and realize these animals are not only cool, but they’re essential for our own survival.

How To Help:

To support the National Geographic Photo Ark and help stop the rapid decline of many at-risk species, visit the Photo Ark donation page. Your donation supports the National Geographic Photo Ark in continuing its impactful work to educate and encourage people to co-exist more peacefully with local animal populations.

More from Better:

- National Geographic Reveals 2024 ‘Pictures of the Year’: Here Are Some of the Most Fascinating

- ‘Together, We Are Making Big Waves’: Pioneering Marine Biologist and National Geographic Explorer Sylvia Earle Says It’s Not Too Late to Save Our Oceans

- Jane Goodall Shares 3 Reasons She’s Optimistic About the Future of the Environment

Assignments have taken award-winning photographer and Make It Better Foundation Director of Photography Mark Edward Harris to more than 100 countries on all seven continents. His books include Faces of the Twentieth Century: Master Photographers and Their Work, The Way of the Japanese Bath, Wanderlust, North Korea, South Korea, Inside Iran, The Travel Photo Essay: Describing A Journey Through Images and his latest, The People of the Forest — a book about orangutans. He proudly supports the Center for Great Apes, the Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation, and the Search Dog Foundation. You can find him on Instagram or at his website.