More than 50 years after the end of the Vietnam War, the environmental and health consequences of “Operation Ranch Hand” — the U.S. military’s aerial spraying of herbicides containing dioxin — continue to unfold. Agent Orange, the most widely used of these herbicides, left behind contamination in the soil, water, and food systems of Southeast Asia, as well as chronic illnesses among both Vietnamese civilians and U.S. and allied veterans.

Agent Orange’s environmental and human toll did not end with the signing of a peace treaty in 1973 or the reunification of Vietnam two years later. Studies have confirmed the presence of dioxin residues in the soil of Southeast Asia and in the blood, fat tissue, and even breast milk of people on both sides of the conflict — decades after the last spray missions.

The Effects of Agent Orange

Dioxin (specifically TCDD) is a fat-soluble compound that persists in the environment and accumulates in the food chain, entering the human body primarily through consumption of contaminated food, particularly animal fat. Exposure affected both Vietnamese civilians and American and allied military personnel, with some studies suggesting dioxin may cause transgenerational effects, including birth defects in the children of those exposed.

In 1961, South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem formally requested U.S. assistance in defoliating jungle areas that provided food and cover for Viet Cong forces. The U.S. military conducted herbicide spraying operations from 1962 to 1971, not only in Vietnam but also in parts of Laos and Cambodia during the war.

In the United States, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has recognized a range of cancers and other health conditions as “presumptive diseases” associated with Agent Orange exposure. The agency also presumes that certain birth defects in the children of Vietnam veterans may be linked to the veterans’ military service, making some family members eligible for benefits.

Veterans who served in specified areas along the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) may also qualify for similar benefits. The VA has additionally acknowledged that Agent Orange and related herbicides were tested, stored, or used at military sites across the United States.

A Long History With Agent Orange

Although Agent Orange is most closely associated with the Vietnam War, its use and production began earlier. In the late 1940s, herbicides containing dioxins were developed in the United States for agricultural and industrial use — including controlling undergrowth near power lines and railroads. During the Vietnam War, the U.S. military procured more than 20 million gallons of herbicides — including Agent Orange — from multiple chemical manufacturers.

Even before the U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam in 1973, federal agencies had begun to address growing concerns about the health and environmental impacts of these chemicals. In 1972, the U.S. Air Force launched Operation Pacer IVY to remove stockpiles of Agent Orange from Vietnam and store them on Johnston Atoll in the Pacific. In 1977, a follow-up operation known as Operation Pacer HO oversaw the incineration of approximately 1.8 million gallons from Johnston Atoll and an additional 480,000 gallons stored in Gulfport, Mississippi. The chemical was destroyed aboard the Dutch-owned waste incineration ship MT Vulcanus, which operated at temperatures exceeding 1,830°F to break down the dioxin compounds.

However, the issue didn’t end with disposal at sea. In the mid-1980s, New Jersey declared a state of emergency along part of the Passaic River due to contamination at a former Agent Orange manufacturing site operated by Diamond Alkali. Decades later, the EPA released a $1.4 billion cleanup plan for the area, and remediation efforts remain ongoing.

More recently, the U.S. government has collaborated with Vietnam to assess and clean up remaining environmental hot spots. Beginning in 2005, the EPA and USAID partnered with Vietnamese authorities to evaluate contamination at the former Da Nang Air Base — a key storage and handling site during the war. In 2012, the first major joint cleanup effort began at the site, using a process known as in-pile thermal desorption (IPTD). The treatment of contaminated soil was completed in 2017, marking a historic milestone in bilateral environmental cooperation.

Exploring the Lasting Impact

With diplomatic relations warming, tourism has surged — nearly 780,000 Americans visited Vietnam in 2024, making the U.S. the country’s fourth-largest source market. For visitors to Ho Chi Minh City, the War Remnants Museum (formerly the “Exhibition House for American Crimes”) is a key cultural site. Among its thought-provoking exhibits is a gallery featuring 42 photographs by Japanese photojournalist Goro Nakamura, documenting the long-term effects of Agent Orange on Vietnamese civilians, U.S. troops, their allies, and their descendants.

Born in Japan’s Nagano Prefecture in 1940, Nakamura has authored five books on Agent Orange (in Japanese) and currently serves as the deputy director of the Institute of Modern Photography in Tokyo. This interview began in Ho Chi Minh City in English and Japanese during Vietnam’s 50th anniversary reunification commemorations and continued by email.

Mark Edward Harris: When and why did you first come to Vietnam?

Goro Nakamura: I first arrived in Vietnam in June 1970 as a correspondent for the Japan Press news agency to cover the U.S. bombardment of North Vietnam. I went to Hanoi three times during the war, staying for one or two weeks each time. In 1973, I entered South Vietnam’s Quang Tri province. In May 1975, just after the war, I visited Saigon with many other Japanese journalists. I have gone back many times since.

MEH: How did you end up pursuing Agent Orange as a long-term project?

GN: I first learned about the damage Agent Orange was causing in the jungles of South Vietnam through the news coming from the Vietnam News Agency at the beginning of the 1970s. But it wasn’t until 1974 when I visited the Binh Linh district near the boundary of North and South Vietnam that I began to document its devastating effects. In this area, I found a shocking scene caused by the spraying of Agent Orange. Almost all the people there were obliged to live in underground tunnels to survive. Seeing the apocalyptic landscape and hearing the stories of the local Vietnamese, I became determined to cover in depth the tragedy of the Agent Orange operation.

MEH: It was surprising to learn that Agent Orange was primarily used in South Vietnam, an ally of the United States.

GN: The chemical spraying operation’s goal was to expose and destroy Viet Cong bases in the jungles in South Vietnam, and also to destroy farmland to disrupt the food supply for the Viet Cong. Of course, that impacted South Vietnamese civilians. The operation by mostly USAF C-123 planes continued daily from 1961 to 1971 using the chemical compounds of dioxin-contaminated 2,4,5-T and 2,4-D organochlorinated herbicides. The problem is that the 2,4,5-T included 2,3,7,8-TCDD, the most toxic 4-chlorinated dioxin, which causes many kinds of cancer, and leads to abnormal childbirth with many deformed babies.

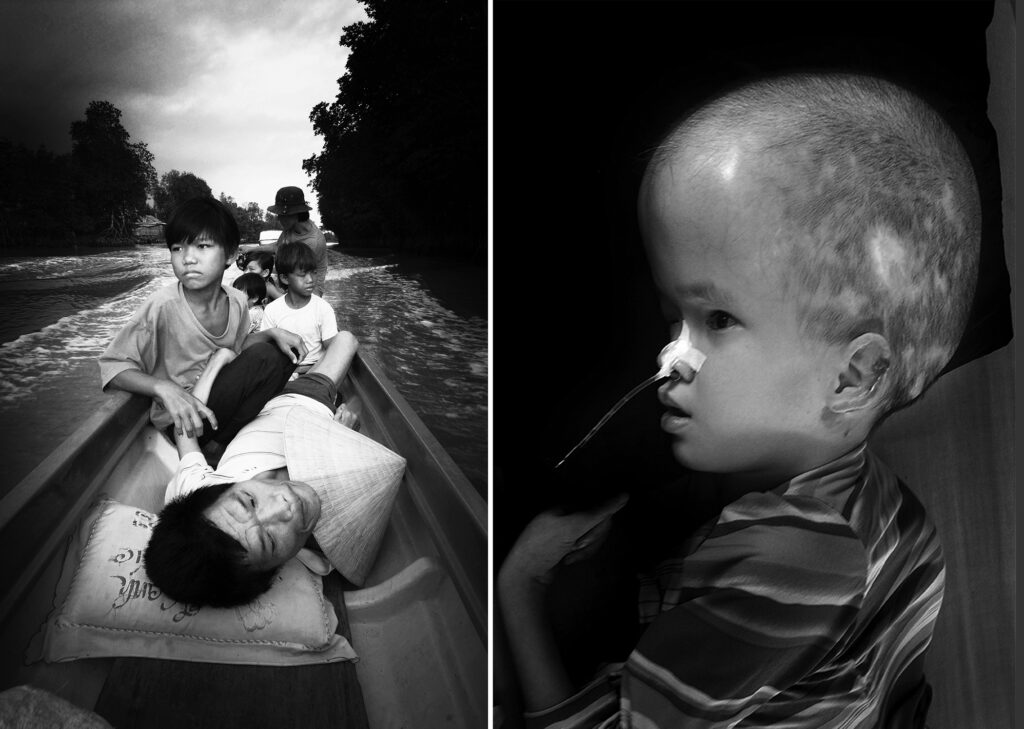

MEH: One of your most well-known photographs is of a boy in a mangrove that Agent Orange destroyed.

GN: That picture was taken in June 1976 in a mangrove jungle in Cape Ca Mau, that’s in the southernmost region of Vietnam, at the end of my longitudinal trip from north to south to document a unified Vietnam. The country had been unified since April 30, 1975, with the Fall of Saigon. Of course, the damage caused to the country has continued long after that date.

As for this photo, it was just by chance because we were obliged to get on a small canoe and travel through the jungle to reach the tip of Cape Ca Mau. We came across a destroyed forest. It was a world of death. I landed there, got out of the canoe, and soon met a boy in this dead forest.

Twelve years later, I revisited the area to try and find the boy. It was shocking. He appeared in front of me with his paralyzed body. In 2007, he was bedridden, and then in 2008, he passed away due to kidney cancer. He was one of the typical victims of Agent Orange, born in the forest under the spraying operation during the war. In 2009, I went to the village again and burned incense at his tomb. I have continued to go to this area every few years.

MEH: How are Agent Orange victims treated for their medical issues in Vietnam?

GN: Among the millions of Vietnamese people who have suffered from Agent Orange spraying are 200,000 malformed children. Almost all the deformed children cannot be cured. The continuing tragedy of dioxin contamination is that it still spoils people’s bodies to this day, appearing not only in the generation after the war but also in the third generation. For example, last summer, I documented these latest victims in Ben Tre, Vietnam. Epigenetic studies back this phenomenon. The Vietnamese government provides small monthly stipends to its citizens who are believed to have been affected by the herbicides. Other governments and NGOs have also helped with health care, site cleanup, reforestation, and other services.

During the war, I used two or three Nikon SLR film cameras, and now I use digital cameras, but the problem I’m covering hasn’t changed. People are still suffering from this horrible use of chemicals as we sit here in Vietnam, 50 years after the war.

MEH: What are some of the stories behind the people you’ve met in your long-term coverage?

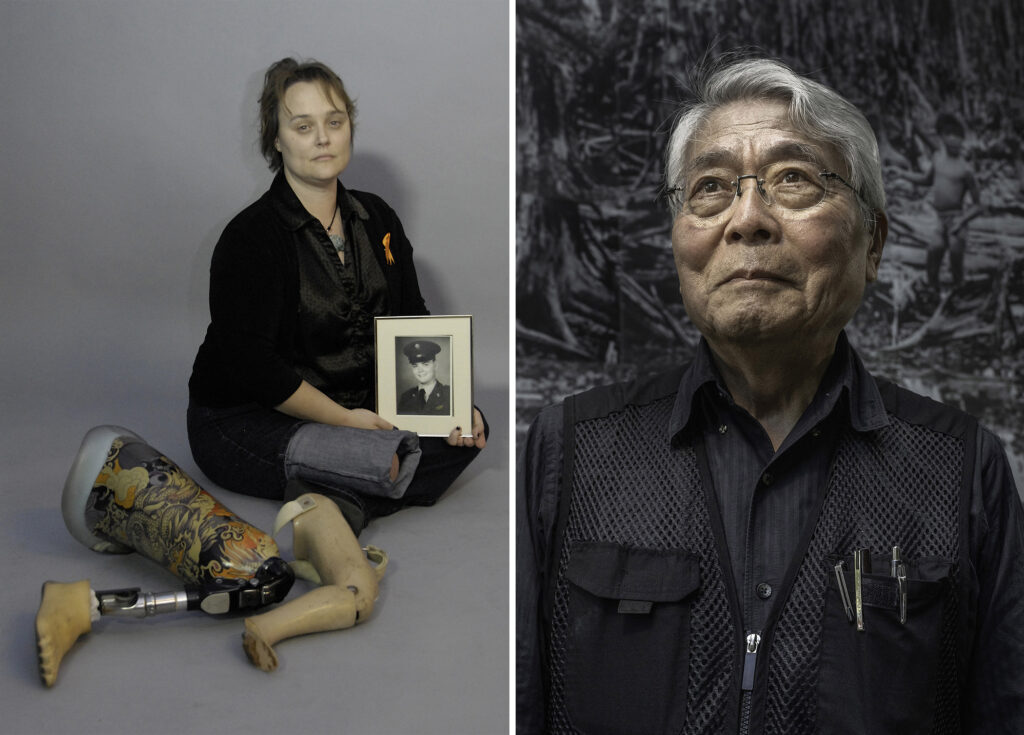

GN: Most of the suffering people in Vietnam live a poor life, but they do not give up. I have also documented several Americans who have suffered from Agent Orange. In the summer of 2011, Heather Bowser stopped off in Japan on her way back from Vietnam, where she had finished shooting her documentary film, “Living the Silent Spring,” directed by Masako Sakata. It was about her life as a victim of Agent Orange. We met, and she was not shy about telling me about her handicap, which is the loss of her feet and fingers. At the same time, she told me that when she interacted with the disabled children in Vietnam, “I was shocked to discover that they had the same condition as me, and I felt like I had met my brothers and sisters.”

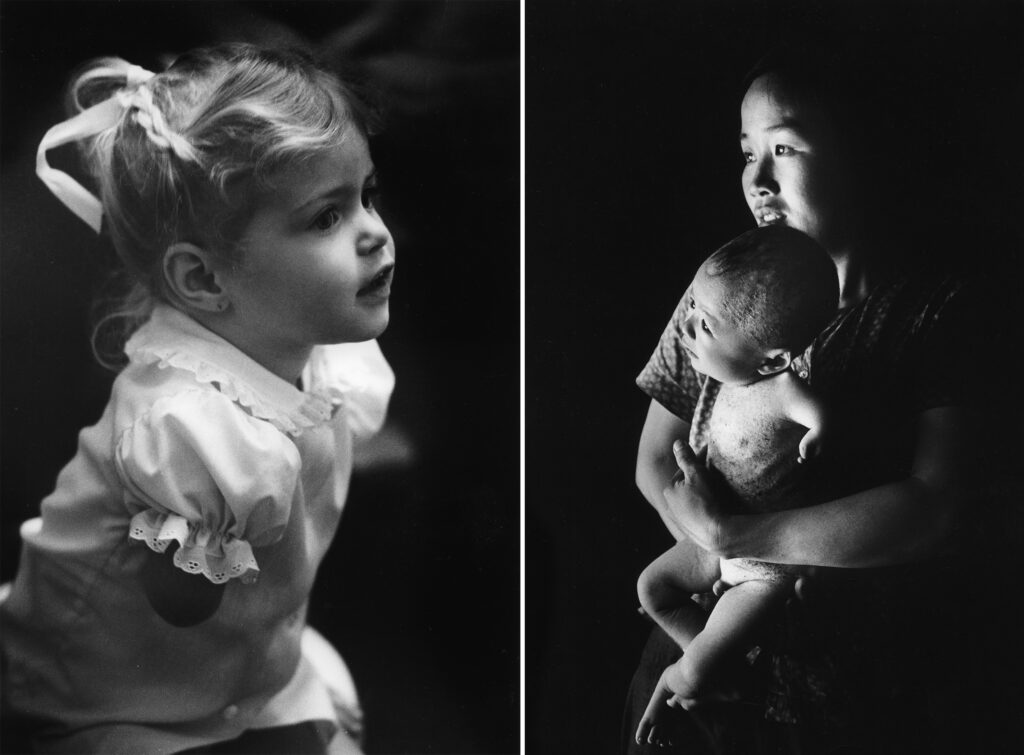

In Ho Chi Minh City, Heather also visited the War Remnants Museum. There she saw my photo of Jennifer, a child of an American Vietnam veteran, whose photograph I had previously exhibited with her right arm missing. I was surprised and moved to discover that I had friends in America.

MEH: What’s Heather’s backstory?

GN: Her father, Bill Morris, was drafted in 1967. He was stationed in Vietnam from 1968 to 1969 at Long Binh Post in the Dong Nai Province. The dangers of Agent Orange were not communicated to the soldiers on the front lines. It was sprayed not only on farmland and forests, but also in the tall grass surrounding the base to prevent guerrillas from infiltrating.

After Bill returned home, Heather was born to her mother, Sharon, on October 7, 1972, without a right leg below the knee and many missing fingers. Sharon kept blaming herself, thinking, “Maybe I did something wrong.” Then she learned that Agent Orange was the cause. Blaming themselves for their child’s health issues was a common reaction among many mothers in Vietnam as well.

Returning home to Pittsburgh, Heather contacted Jenny in Philadelphia, whom she had seen in my photos in Vietnam. They came to understand that their disabilities were not the fault of their parents or themselves, and that they were both victims of Agent Orange, and so they banded together to seek compensation.

Through research and a network of contacts, on April 14, 2012, about 10 children of veterans from across the United States gathered at Heather’s house in Canfield. I was also invited from Japan. There, the formation of the Children of Vietnam Veterans Health Alliance (COVVHA) was announced. Heather became the founder of this NPO organization.

Since then, COVVHA has been lobbying the US government, but the government has remained hesitant to accept its demands. The theory of transgenerational epigenetics, elucidated by Professor M. K. Skinner of Washington State University and his colleagues, was published in the magazine Science in 2005. This publication showed that even if no DNA damage occurs in the nucleus of reproductive cells, toxicity can loosen the helical state of DNA and disrupt genetic information. Birth abnormalities can occur even if toxic substances such as dioxin are not detected in the blood of the second or third generation. The US government has refused to provide compensation and relief to these children.

[COVVHA’s last Facebook post on August 30, 2022 said: “We are closing the business end of COVVHA…this is due in part to our own declining health, overall lack of interest and bleak prospects for making wider change in the current environment since the overturning of the Agent Orange act of 1991. COVVHA’s first mission was to educate, and our overarching mission was to create change for the good of the kids of Vietnam Veterans. We have done both of those things, just not in the way we expected. I cannot tell you how fulfilling it is to watch COVVs connect. We may not have won in DC, but I have so many wonderful people in my life who understand AO. I never have to feel alone again.” Warmly, Tanya Mack, Valerie A G Ouillette, and Heather Morris Bowser.]

MEH: What’s Jennifer’s backstory?

GN: I met her father, Daniel Loney, a paratrooper with the 173rd Airborne Brigade of the U.S. Army, in November 1982. His 240-pound frame showed tireless fighting spirit on the battlefield, and he even earned a Bronze Star.

He was sent to Vietnam from Okinawa in late 1966, to the jungle area of Boi Loi, also known as the Parrot’s Beak. He talked about the experience. “The fighting was brutal. During the operation, we slept in the mud. The forests, where defoliants had been sprayed, had a smell like fuel. When I got thirsty, I would put an odor-eliminating purifying agent in the river water and gulp it down.”

In 1967, he successfully parachuted into Kon Tum and was deployed to the “toughest fighting” in the Central Highlands. In 1968, he began suffering from high fevers every day. He was admitted to a hospital in Cam Ranh, but the cause was unknown, and he became delirious. His hair fell out in clumps, and his hands and feet began to go numb. He also had hearing loss, dermatitis, migraines, and gastritis.

After the war, he learned that there could be genetic disorders in his children. His daughter Jenny was born in 1980. He recalled, “When my wife Virginia was four months pregnant, I asked a doctor at the Veterans Administration Hospital if the defoliants would affect our baby. The doctor looked at my ears, nose, and throat and assured me that I and my baby would be fine.”

When I visited their house in a corner of Philadelphia, I saw Jenny, who was two and a half years old, playing innocently. But she was missing her right arm. Daniel was convinced that Agent Orange caused this, and he signed his name to a lawsuit filed by returning soldiers against Agent Orange.

MEH: What happened to both Daniel and Jenny?

GN: In 1994, Jenny was 14 years old. Daniel was beginning to suffer from five different types of cancer. He was in and out of the hospital. Nightmares from Vietnam kept coming back and disturbing his nerves. He had severe PTSD. In 2003, while in the hospital, he pulled out a gun, pointed it at himself, and pulled the trigger. He was 57 years old.

I met Jenny again in 2011 when she was 31 years old with a cute daughter, with nothing physically wrong with her. But Jenny ended up getting divorced, forcing her to work three jobs. “I can only use my left hand to type on the keyboard, and I’m slower than everyone else, so it’s a problem,” she told me, smiling.

She was sure that even more difficult things were waiting for her in the future. That’s the reality for so many people on both sides of the Pacific because of Agent Orange. While any war is terrible, we have to learn that the use of chemical weapons causes tremendous pain long after peace treaties have been signed.

How to Help:

Join the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund (VVMF) in honoring the thousands of Vietnam veterans who have suffered as a result of Agent Orange exposure on Agent Orange Awareness Day on Aug. 10, 2025 when VVMF will host a candlelight ceremony at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial to bring light to the war’s continuing toll. Thousands of orange candles will be placed at the memorial to honor the many veterans who returned home only to face devastating illnesses caused by Agent Orange exposure.

You can sponsor a candle or purchase a T-shirt to help bring Agent Orange awareness to light. You can also support veterans affected by Agent Orange and other service-related conditions through the VVMF’s In Memory program, which honors those who died after returning home.

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund (VVMF) is a nonprofit organization dedicated to honoring Vietnam veterans, preserving the legacy of service, and educating future generations about the Vietnam War and its ongoing impact. Best known for establishing “The Wall” in Washington, D.C., VVMF continues to serve as a powerful force for remembrance, healing, and advocacy. Donate to support their mission.

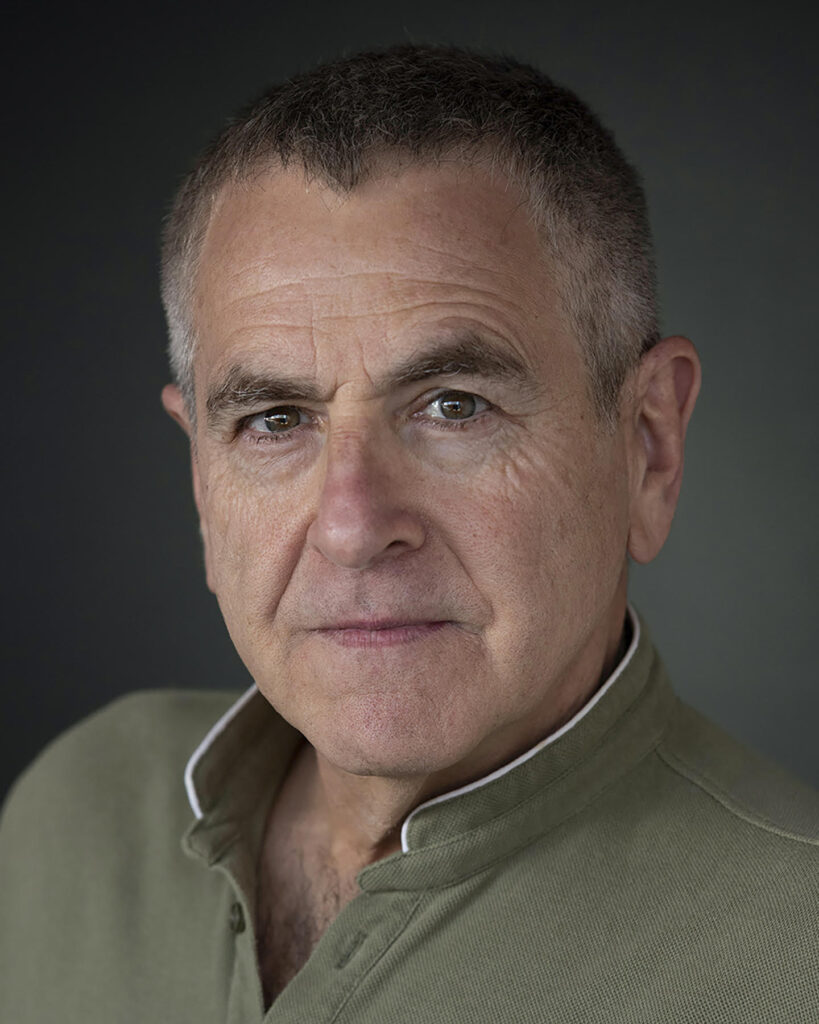

Award-winning Director of Photography Mark Edward Harris

Mark supports:

Center for Great Apes

Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation

Search Dog Foundation

His books include:

Faces of the Twentieth Century: Master Photographers and Their Work

The Way of the Japanese Bath

Wanderlust

North Korea

South Korea

Inside Iran

The Travel Photo Essay: Describing A Journey Through Images

The People of the Forest