As part of our “You Said It” Op-Ed series, we invite contributors to submit their opinion pieces, like the one that follows. Have a story? Here’s how to submit it.

Survivors of abusive relationships know that you can be hurt without ever having been hit. You can be a survivor of domestic abuse without any physical trace left behind.

“Where are the bruises?” they ask.

Real but invisible.

“Where are the scars?” they insist.

Real but invisible.

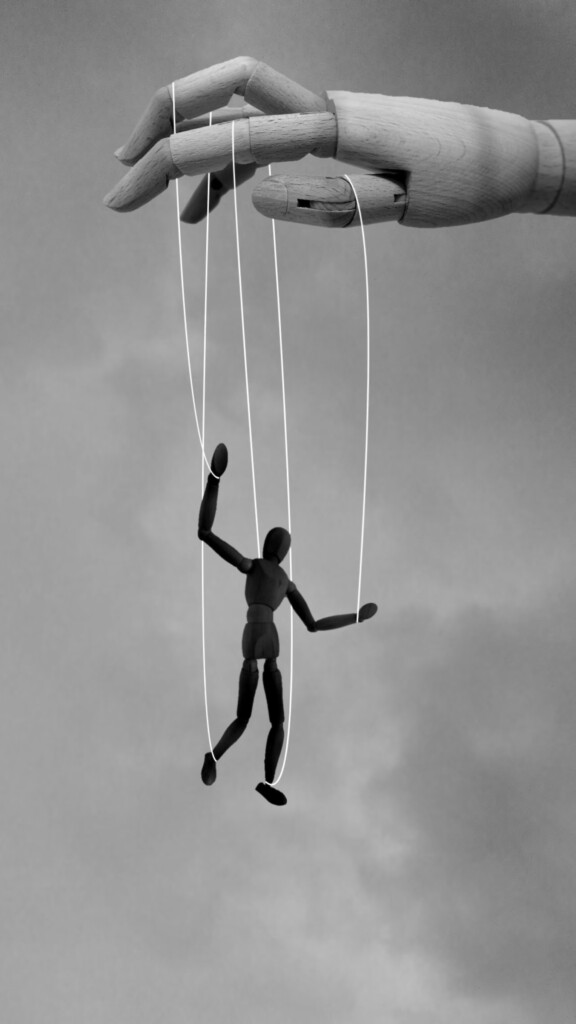

Even if you have not experienced Machiavellian manipulations in a relationship of your own, you’ve likely seen it play out in movies, TV shows or in the life of a friend. We have to but only close our eyes and a picture readily arises in our mind: an abuser skillfully weaponizes the vulnerabilities of a victim to undermine their reality, with results that can be just as devastating as physical abuse.

For those watching from the outside, the answer seems painfully obvious: Don’t stay. Don’t give them another chance. Just go! Yet, those suffering at the hands of an emotionally abusive partner — a gaslighter — know too well that leaving an asymmetrical power dynamic is never as simple as walking out the door. These situations are made all the more tragic by the realization that domestic violence laws and legal recourse available to victims of abusive relationships characterized by gaslighting and coercive control have been devastatingly desolate, disproportionately recognizing only those with visible scars which “prove” their abuse.

Just ask Lynne.

In May of 2022, just shy of his 22nd birthday, Lynne’s son died as a result of substance abuse. She sees this terrible tragedy as a heartbreaking consequence of her family’s inhumane and traumatic treatment by the family court system — a system that, for 16 years, failed her and her children’s well-being while she tried to escape her ex-husband’s gaslighting behavior and coercive control. She said, “If the behavior had been named, it could have been tamed.”

This is Lynne’s story.

Failing Family Court Systems — A Victim’s Story

Lynne was an attorney who participated in domestic abuse and mediation training in her thirties. But even her professional background did not protect her against the insidious tactics of a gaslighting husband. First, there was six years of being shut out of household financial information and only having access to a joint credit card and a small allowance. Alongside this maltreatment were a myriad of other coercive tactics aimed at breaking her will. Finally the dam broke — Lynne filed for divorce. She hoped that would be the end of the abuse, but it was just the beginning of another cycle.

Following the divorce, Lynne initially held a hybrid custody agreement, which afforded her some decision-making power in terms of religion and a say in the children’s educational processes. But she was still on the outside looking in regarding medical treatment for her offspring. Because the two of them were tied financially, Lynne watched as her ex-husband’s controlling behaviors reached new heights. He canceled her credit card and refused to provide financial support, at the expense of their children’s welfare. As a result, their living conditions deteriorated, leaving Lynne constantly stressed. She eventually fought and gained sole custody to stem the tide of these financial abuses, but the damage was done. Over 16 years — before, during and after the divorce — she battled a legal system that failed to hold her ex-husband accountable for coercive control. She soon realized defeatedly that any effort to pursue just action would cost more money than the reimbursement dollars at stake.

Lynne’s own words clarify the depth of her suffering. “For years he stonewalled, he sent abusive emails, failed to cooperate with professionals, lied to the kids, harassed and threatened staff at my kids’ school and threatened my husband. My husband had a series of meetings with him, and in the last one he said that if I didn’t agree to meet with him, he’d undermine everything I [do] with the kids.”

At peaks of desperation, Lynne confessed that she wished her ex-husband would hit her, if only to be given the recognition more often afforded to victims of physical abuse. For years the abuse continued, invisible to family court thanks to gender biases that deemed Lynne too “shrill and angry” to be taken more seriously. She and her children struggled, with corrosive effects that would last a lifetime.

Lynne’s story — one characterized by coercive control and gaslighting at both the interpersonal and systemic levels — is tragic. Unfortunately, it is not unique.

Coercive Control and Gaslighting Defined

Coercive control is a form of nonphysical abuse in which a pattern of behaviors characterized by intimidation, threats and humiliation are weaponized to erode an individual’s autonomy and self-esteem. It is intimate partner violence designed to isolate an individual from any source of outside support and independence. Research also shows that it is often a predictor of future physical interpersonal violence.

A precursor to coercive control, gaslighting and its effects include a psychological takeover that happens subtly, slowly and with intention. Deliberately inflicted wounds of shame, obligation or indebtedness are meant to reinstate a gaslighter’s sense of power in the relationship, further belittling the gaslightee. This, in turn, empowers the gaslighter in their quest to feel dominant and in control of the relationship. Emotionally adept individuals cunningly marshal their ability to read others well and deploy it to bully and manipulate others. Their victim’s emotional and psychological safety is preyed upon by a combination of tactics: persistent denial, reality-spinning, blaming, shaming, contradiction and outright lying.

Importantly, gaslighting behaviors are not just relegated to romantic partnerships. Platonic friendships, family relationships and professional relations are also fair game. More to the point here, gaslighting can happen in the courtroom, with lawyers and psychologists, and all involved in the family court system. It occurs wherever there are people, power dynamics and an intent to destabilize someone for personal edification. Gaslighting is a slippery slope into coercive control and domestic abuse.

Seeds of Change in The Courts

Unfortunately, domestic abuse laws and family court systems are still catching up with the reality of gaslighting and coercive control in abusive relationships. A global surge in domestic violence with the COVID-19 pandemic sparked desperately needed updates in some U.S. states and throughout the world. But this momentum must continue with strict laws and coercive control bans throughout legal systems to address the myriad of methods by which partners can manipulate technology and finances to gaslight and control others. For example, restraining orders have historically excluded non-physical actions per standard definitions of domestic abuse. If coercive control is a predictor of future physical interpersonal violence, then it must be considered across legal definitions of domestic abuse.

To be sure, the National Network to End Domestic Violence now defines domestic abuse as “a pattern of coercive, controlling behavior that can include physical, emotional/psychological, sexual, and/or financial abuse.” It goes on to note that financial abuse is a common tactic used by people who choose to inflict harm through the control and isolation of their partner, which can have far-reaching and devastating consequences.

Attorneys are beginning to understand the devastating effects of gaslighting in interpersonal relationships. In recent years, there has also been a rise in legislation to address the reality of coercive control in many domestic abuse cases. In 2020 California revised the State’s Family Code to include coercive control. In 2021, a bill approved in Connecticut broadened the state’s definition of domestic violence to include a broader definition of coercive control as “a pattern of abusive behavior that seeks to control a victim through emotional and psychological tactics.” This encompasses isolation, restricting access to money, or threatening to harm an individual’s children or pets.

Furthermore, in 2022, Washington’s House Bill 1901 went into effect, adding coercive control to the state’s definition of domestic violence. In 2023, Maryland followed suit with Rule 9-205, which modifies the requirement for mediation if there is any threat of abuse — physical or emotional. Change is underway.

The Road Ahead for Coercive Control Laws

Still, it is not enough.

Again, Lynne’s own words offer a rallying cry: “[Coercive control] needs to be [in] the law and definition of domestic abuse in every state. It’s not okay for a woman in Iowa to have to demonstrate physical abuse to get protection, while a woman in California can show coercive control. This is the call to action!”

These coercive control laws may be one step in the right direction but, in reality, they do not help victims who prefer to seek help without involving legal intervention. Nor do they always successfully mitigate the skepticism of judges with “misogynistic overtones” who they may end up standing before, asking to be believed. Enacting laws without addressing the necessary cultural and systemic reforms across police, judiciary and community sectors runs the risk of further traumatizing victims by forcing them to endure inadequate legal recourse.

A Final Rallying Cry

Lynne’s story is one of too many jarring calls to action for lawyers, legal advisors, judges, policy makers and legal systems alike to take coercive control seriously as a form of domestic abuse. She shares her story in hopes that the interdisciplinary systems victims of domestic abuse must navigate will finally understand the compelling reasons to name, define and hold accountable those who are the emotional and financial abusers in a relationship. While some progress in many states and legal systems has been made, this change must be widespread.

Lynne reflects often on the premature death of her son, saying, “My children were also abused by gaslighting [and] coercive control, and my son, perhaps because of gender or vulnerability, was made sick by the abuse. With each therapist I took [him] to, I’d start the story all over again trying to explain the behavior and get [him] help.”

Sadly, no healing balm for the invisible bruises and scars of coercive control were to be found for this brave mother and her children caught in the crossfire. Lynne does not want anyone else to experience the abuse and heartbreak she has.

No one should.

We can do better. We must do better.

If you or someone you know is a victim of sexual or domestic violence in need of assistance, call 877-785-2020 or visit Jane Doe Inc. online.

Robin Stern, PhD, is the co-founder and senior adviser to the director of the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence, a psychoanalyst in private practice, the author of “The Gaslight Effect Recovery Guide” and the host of The Gaslight Effect Podcast.

Lynne Singer Redleaf was a practicing attorney, and now serves as the President of her private family foundation.