Cecilia Conrad is that rare individual who can do more work than multiple high-level executives combined, makes it look easy and charms in the process. She is CEO of Lever for Change and Managing Director of the Fellows (Genius Grants) and 100&Change programs. at the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

As a trustee of the Poetry Foundation, which recently came under extreme duress in response to the Black Lives Matter movement, she volunteered to chair the Equity Oversight Committee and calmed significant turbulence by promising thoughtful, impactful change.

She also serves or has served as a trustee for a long and impressive list of other institutions. She’s a very rare breed of economist – Black, Wellesley and Stanford trained, with significant corporate, government and academic experience and multiple awards and publications earned before joining the foundation world – sitting at a strategic intersection for these challenging times. And she’s the perfect women for the opportunity, as this Q&A hopefully helps you understand too.

What are your thoughts on the big issues in our world right now—COVID-19 and Black Lives Matter—and your hopes for what follows?

I alternate between hope and despair. I’m answering the question on the upside of despair but before I’ve reached peak hope. I am inspired by the large number of people of different races who marched peacefully not only in cities large and small in this country but also around the world. I want to believe that their voices will continue to be forceful over the next months and years. I’m old enough to have observed activism followed by apathy and the fragile gains that we’ve achieved dissipated by economic downturns and reassertions of racial power dynamics. My young colleagues are fond of saying, “nothing has changed,” but that isn’t true. There has been change, but too much of the change has been ephemeral. My hope is that this time is really different.

What is your best advice for individuals or institutions who want to invest philanthropic dollars to help?

The first step is a self-assessment. What is your appetite for activism or advocacy vs more traditional charitable activities?

If you want to help, but want to stick to traditional charitable giving, consider giving to a Historically Black college or University (an HBCU). You can obtain a list of accredited HBCU’s here. These institutions, bulwarks of economic opportunity for African Americans, have been hit especially hard by COVID-19 shut-downs.

My dad’s dad went to Tuskegee Institute, and my dad graduated from Southern University and Meharry Medical. I owe much to HBCU’s even though I didn’t attend one.

If you want to help and are willing to move in the direction of advocacy, I suggest grants to cornerstone organizations who have a history of working on civil rights, voting rights and economic opportunity. For example, I make a donation every year to the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. The Innocence Project, has a guide for how to help specifically related to addressing racial inequity in the criminal justice system. Look the grant portfolios of foundations like Kellogg, Ford and MacArthur too see where they are making grants and copy them.

Finally, it is important to invest in black-led nonprofits. There is a big disparity in nonprofit funding for leaders of color.

Please tell us about your parents and other role models or mentors in life. Specifically, who helped you develop your positive, can do attitude?

My parents were important role models for me. My parents moved to Dallas in 1955 and became involved in the civil rights struggle there. I participated in my first demonstration at age 8 – after Medger Evers was assassinated. One of my earliest memories of my mom was watching her on the evening news – sitting-in at the lunch counter at the bus station, elegantly dressed in a suit with shoes and bags that matched. My father became the first African American elected to a city-wide office in Dallas when we won a school board election in 1967. My mother was the first woman and the first African American to serve as the foreperson on the grand jury. Both held appointments in state agencies. Dad was on the State School Board when he died. Mom was on the Coordinating Board for Higher Education and then on the State School Board (completing my father’s term).

My mother earned her bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the University of Illinois (she grew up in Champaign Urbana). My father’s undergraduate degree is from Southern University and medical degree from Meharry Medical College, but he spent his senior year of college at Stanford in an army unit there.

They demonstrated a strong sense of responsibility to try to make the world better than you found it. They also gifted me with a strong sense of self and with resilience.

Beyond my parents, I was embedded in a community of doers – my parents’ friends. My godmother was a woman named Mabel Curtis who had worked for the League of Nations and had traveled all of over the world. She ran a community art center in St. Louis and instilled my interest in the visual arts.

I could go on and on.

What struggles, if any, did you experience as a Black female growing up in Dallas, studying economics (a male dominated field) and in your early career in business and government?

I earned my undergraduate degree at Wellesley and my graduate degree at Stanford. I decided to be an economist without fully understanding that it was a male-dominated field because I didn’t know any economists. As a pre-teen, I considered becoming an engineer, but I knew an engineer, and he discouraged me by saying that it would be hard enough to be black but even harder to be black and female.

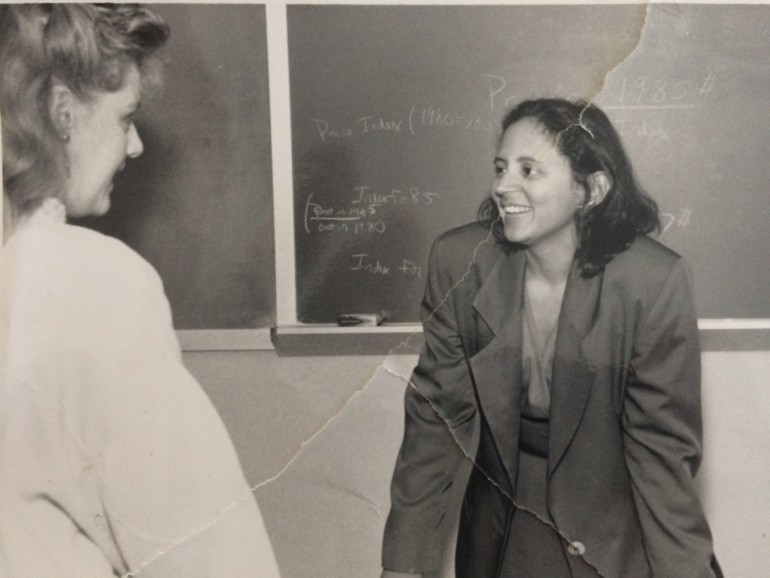

At Wellesley, I met women economists and even had a black woman as a professor – Diann Painter – so I didn’t really think much about the male dominance of the field. I confronted this issue in graduate school. I was one of only 2 women in my class.

How did this inform your later work in academia?

As a student of economics, I was struck by assumptions that were made and the implications of those assumptions that didn’t align with the reality that I experienced. For example, women who were not in the paid labor force were characterized as engaged in leisure activities. Blacks who were unemployed were assumed to lack education or have criminal records – yet I had cousins with college degrees, work experience, and no encounters with criminal justice who couldn’t get job interviews. I could see that the income comparisons left out non-income factors that impacted well-being – no grocery store in the middle-class black neighborhood where I grew up. These observations fueled my teaching and research.

Please tell us about your husband and son.

My husband, Llewellyn Miller, is an applied mathematician who has worked in finance and in urban development and planning. He was an early contributor to the development of mortgage-backed securities (before they took a bad turn). He served on the city council in Claremont, CA, elected to office after a police shooting of an unarmed, young African American man on his way home from work. His parents and older sisters were born in Barbados, and he was born and raised in New York City. We met on a date arranged by his ex-girlfriend. Llewellyn went to Yale for undergrad and Stanford for graduate school (we didn’t meet at Stanford).

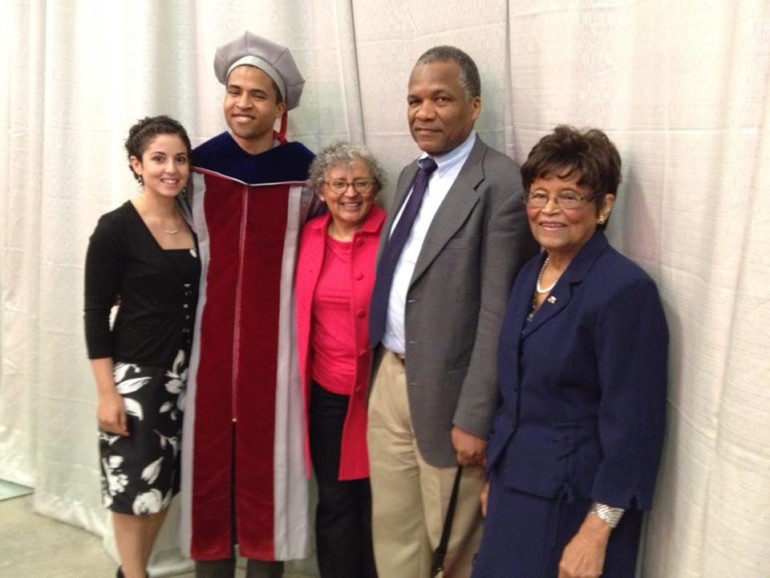

My son is Conrad Miller; he’s 32. He’s married to Shahrzad Zarafshar and they live in Oakland, CA. He is an assistant professor of economics at the Haas Business School at UC Berkeley. He and Shahrzad earned their undergraduate degrees from Stanford. He earned his PhD from MIT. He is an applied economist/data scientist.

You were serving as Acting President of Pomona College when you answered the call to become a MacArthur Foundation VP. With your credentials, you likely were presented with many different opportunities. What attracted you to MacFound?

I can’t say that I was presented with many opportunities in business and government, but there were interesting opportunities in academia. However, it was time for a shake-up. As we get older, it is good to learn new things, take on new tasks. And leading the Fellows program is the coolest job in the world.

As Managing Director of the “Genius Grants” program, you give away transformational amounts of money to inspiring individuals around the world who often didn’t even know they are being considered for the grant. You don’t have to deliver bad news or ask for money either. Nonetheless, you volunteered for the harder jobs of launching 100&Change and Lever For Change, which require informing organizations that they “lost” and asking for donations of very large sums of money. Why?

A confluence of factors made me take on the job of 100&Change. First, it was an intellectual challenge – a problem to be solved – how to engage voices outside the Foundation to help us select a recipient for a $100 million grant. Two, it was naivety. I did not have years of experience in philanthropy to understand what the rules/norms were so I was not fully conscious of breaking them. Three, there were creative colleagues who wanted to work on this project with me. Finally, the philosophy behind 100&Change is not so different from that of the Fellows program. We are looking for problem solvers; we are relying on voices outside the Foundation to help us identify the problem solvers and to guide us on the selection of the grantees. The difference is that Fellows is secretive about the identities of participants; 100&Change is transparent.

Please tell us about 100&Change.

February 2019, MacArthur launched a second round of its 100&Change competition for a single $100 million grant to help solve one of the world’s most critical social challenges. 100&Change is a global competition and is open to organizations and collaborations working in any field, anywhere in the world.

In the inaugural round of 100&Change, from 1,904 proposals submitted, Sesame Workshop and International Rescue Committee were awarded $100 million to educate young children displaced by conflict and persecution in the Syrian response region and to challenge the global system of humanitarian aid to focus more on building a foundation for future success for millions of young children. Other funders and philanthropists have since committed an additional $419 million to support bold solutions by100&Change applicants. Many 100&Change applicants found that the competition challenged them to be more ambitious in their thinking, facilitated collaboration among groups to tackle an issue at a broader scale, and enabled them to create proposals they could use to pursue other funding.

This year, on February 19, MacArthur announced the highest-scoring proposals in 100&Change, they are designated as the Top 100, and Lever for Change launched the Bold Solutions Network, which features all 100 proposals from around the world. The Bold Solutions Network is a searchable online collection of summaries of highly-rated, rigorously evaluated proposals or, “bold solutions,” that emerge from all competitions managed by Lever for Change.

MacArthur’s Board of Directors will select up to 10 finalists from these high-scoring proposals this summer, and a final award recipient will be announced in early 2021.

Please tell us about Lever For Change.

Building on the success of 100&Change, Lever for Change was created to unlock significant philanthropic capital and help donors put their resources to work to accelerate social change. Lever for Change helps philanthropists source vetted, high-impact philanthropic opportunities and connects nonprofits and problem solvers to significant amounts of philanthropic capital. We help philanthropists find and fund vetted, high-impact philanthropic proposals either through the design and management of customized competitions or by identifying opportunities from the Bold Solutions Network, a searchable database which contains top-ranked, vetted proposals from all of our competitions.

Through a rigorous, open, and transparent approach, Lever for Change inspires philanthropists to dramatically increase their giving by helping them source and identify the most promising ideas that will significantly impact the issues they care about most.

What are your hopes for the future of all these programs?

To make the world a better place and inspire others to do the same.

Are there opportunities for potential donors with philanthropic budgets under one million dollars to work with Lever For Change and/or MacFound?

Lever for Change’s Bold Solutions Network is an excellent resource for donors who want to identify pre-vetted ideas. Those donors can connect directly with the projects that are included in the database.

What do you like best about your job?

I like being behind the scenes facilitating the work of incredibly creative people and intrepid problem solvers. I encounter inspiring people every day.

You would be a welcome and important addition to any NFP board. Why did you choose the Poetry Foundation?

Thank you. I’ve loved poetry since I was a child. My grandfather used to recite poems to entertain us. My first book of poems was A Child’s Garden of Verses and at one point I could recite them from memory. In elementary school, I was the reigning champion of the oratorical contest (a bit like Poetry Out Loud) and my first “long paper” in junior high was a biography of Langston Hughes. In junior high, high school and a bit in college, I wrote poems. One poem entitled “APATHY” was published in a community newspaper. I remember only a few lines:

We sit and wait. While the bombs fly and the children cry.

We sit and wait. While the world moves on.

What is your favorite poem?

I’ve Known Rivers by Langston Hughes.

Susan B. Noyes is the Founder & Chief Visionary Officer of Make It Better Media Group, which includes Better.

A mother of six, former Sidley Austin labor lawyer and U.S. Congressional Aide, passionate philanthropist, and intuitive connector, she has served on boards for the Poetry Foundation, Harvard University Graduate School of Education Visiting Committee, American Red Cross, Lurie Children’s Hospital, Annenberg Challenge, Chicago Public Education Fund, Lyric Opera of Chicago, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, New Trier High School District 203, and her beloved Kenilworth Union Church. But most of all, she enjoys writing and serving others by creating virtuous circles that amplify social impact.