On a bluff overlooking Tomales Bay estuary lies a little-known cultural treasure: an extraordinary house that, since 1997, has given more than a thousand writers the time, silence and freedom to do their most thought-provoking, society-changing work.

Designed by West Marin architect Jon Fernandez and built in 1989, the cedar-and-redwood writers’ retreat known as Mesa Refuge was originally a second home for abstract impressionist Sam Francis. One of the smallest of the country’s approximately 500 “artists’ colonies,” its existence has at times been as tenuous as the vanishing species its writers have eloquently championed. Hidden on a quiet country road just outside Point Reyes Station, the retreat has temporarily closed for emergency renovations and a major fundraising campaign.

An Incubator for Creativity

Mesa Refuge customarily serves three writers at a time to write about social justice, the environment or the economy. Most of the thought leaders who lug in their notebooks and laptops aren’t famous — yet — and each stays for only two weeks. But the work they produce there has often gone on to earn MacArthur Fellowships, hit best-seller lists, influence public policy, and engender hope for a just, livable world in our complicated times. Van Jones was not yet a CNN commentator or White House adviser in 2004 when he worked on The Green Collar Economy in a writing shed behind the retreat’s main house.

The brilliant African-American policy analyst and public intellectual Heather McGhee had not yet fully formulated the ideas that animate The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together, her challenge to the notion that racism is a zero-sum game benefitting whites, when she came here in 2017. Mesa Refuge, she says, “was the first place where I got to spend quiet time away, workshopping the ideas with like-minded writer-activists.” Her TED talk two years later, “Racism Has a Cost for Everyone,” has now been watched by more than two-and-a-half million people. And The Sum of Us was an immediate 2021 New York Times best-seller. Samin Nosrat had not yet published her charming how-to-cook book, Salt Fat Acid Heat, when she came here in 2011, and agribusiness critic Michael Pollan (whom Nosrat taught to cook) had not yet published his breakout best-seller, The Omnivore’s Dilemma.

But in a single fortnight here in the spring of 2005, uninterrupted by email, child care or phone calls, Pollan drafted a full chapter on his experiences foraging for mushrooms — astonishingly speedy output for the slow work of paradigm-changing writing. “It was a wildly productive two weeks,” recalls Pollan, who is now a member of the Refuge advisory board, along with environmental writers Bill Mc Kibben and Terry Tempest Williams. “I was astonished at how much I could get done and still go hiking every day — and even go abalone diving off Pierce Point.” Pollan returned in 2007 and wrote a full third of his first draft of In Defense of Food. “I’d always thought these places were a kind of indulgence,” he says. “But my experiences at Mesa have convinced me of their value, and my time there was an incredible blessing. The work people do here has the capacity to change the world, and that is why I have supported Mesa Refuge ever since.”

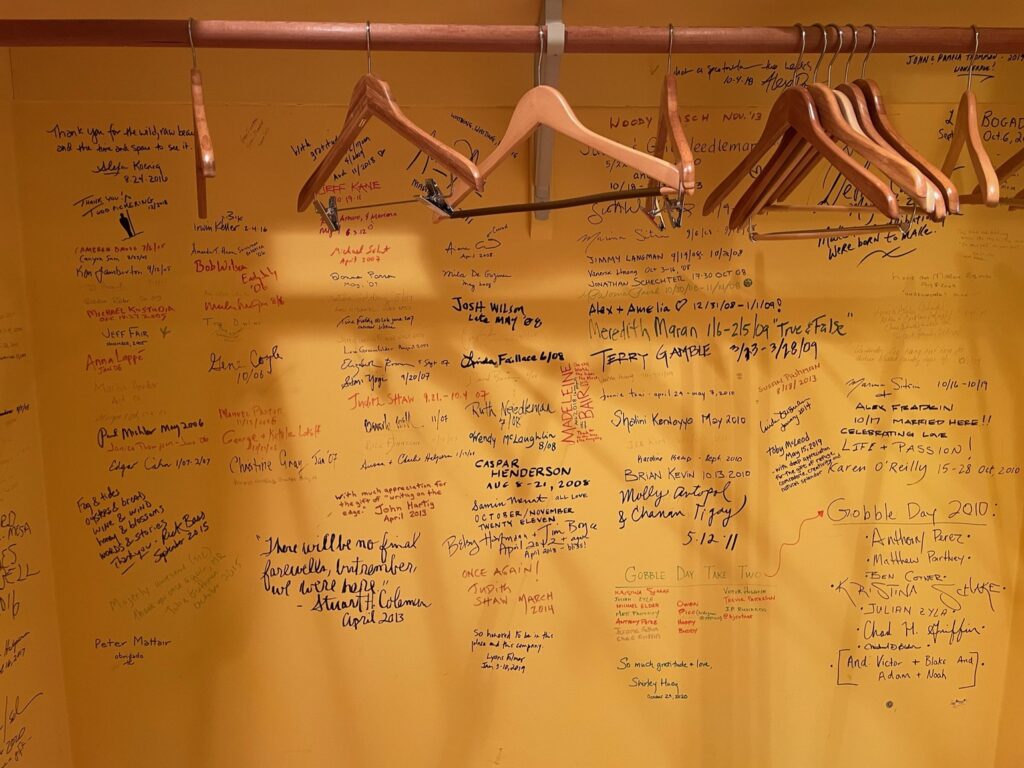

Traditionally, past residents sign their names inside their bedroom closets, and among the signatures you will find those of Shane Bauer (American Prison); Peggy Orenstein (Boys and Sex); Lewis Hyde (The Gift); Lynne Twist (The Soul of Money); Robin Kimmerer (Braiding Sweetgrass); Novato native Rebecca Solnit (Hope in the Dark); Muir Beach Zen teacher Wendy Johnson (Gardening at the Dragon’s Gate); palliative care specialist Sunita Puri, M.D. (That Good Night); and Bonnie Tsui (Why We Swim).

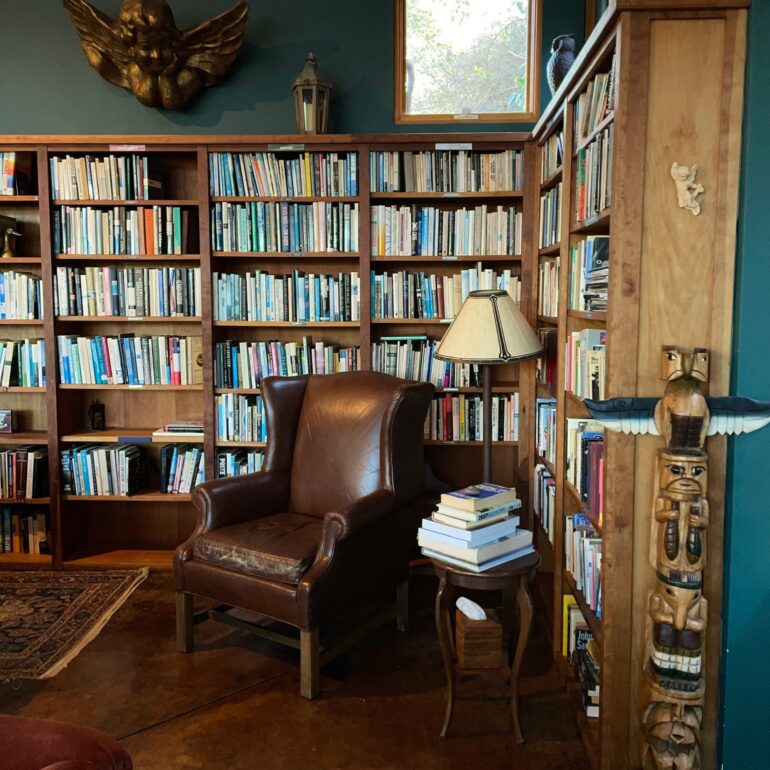

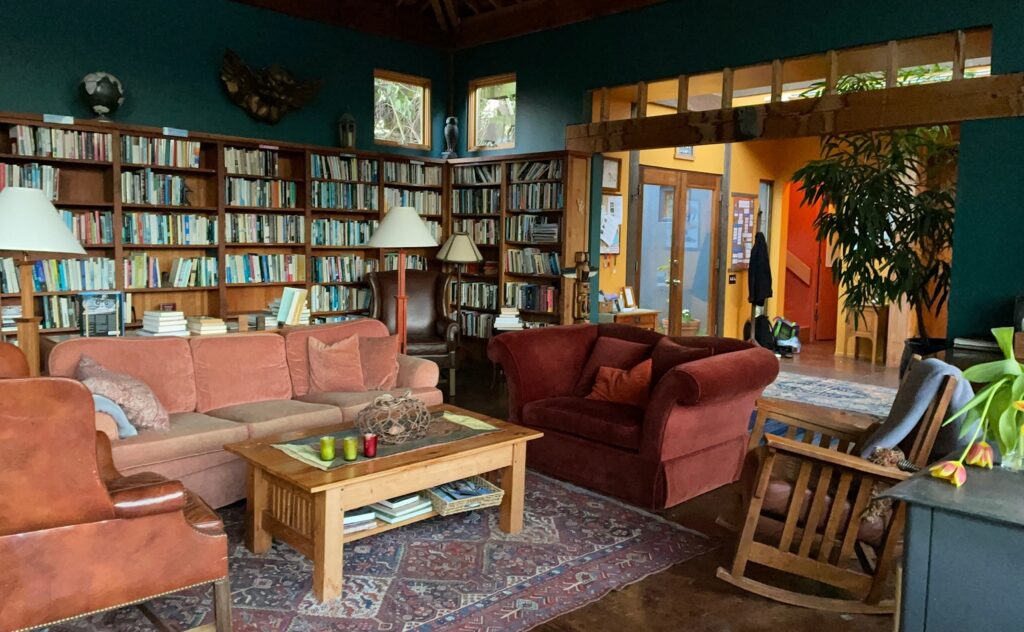

The source of the magic here is elusive. At first glance, the place holds little more than an overgrown English garden with eight apple trees, two freestanding writing sheds overlooking the ever-changing wetlands, and a one-and-a-half story main house constructed of wood, glass and stucco and capped by a skylit entryway. There are three bedrooms; four patios and decks; a gourmet kitchen where residents cook and sometimes share meals; and a high-ceilinged, hip roofed “gathering room” with Mission furniture, rocking chairs, a fireplace, exposed rafters and big glass windows with a long view of Inverness Ridge. The bookshelves are lined with hundreds of books by Mesa Refuge authors.

My Time at Mesa

I wish I could better deconstruct the power of the place, with its timeless sense of wabi-sabi (the Japanese notion of the beauty of the worn, handmade, original and imperfect). But having benefited from three Mesa Refuge residencies myself over the past 20 years, I can testify that everything about the place — the quiet, the privacy, the unpretentious beauty, the absence of human visitors, the presence of birds and flowers, the wordless encouragement to do deep thinking and writing — nourishes the writer’s soul and inspires her best work. I came to “the Refuge” in 2012 as a relatively unknown journalist struggling to wrestle my first book (a memoir of family caregiving and a radical critique of medicine’s technological approach to death) into final shape. As soon as I saw the sign reading “IMAGINE” over the front doorway and took in the interior’s ochre, burnt orange and deep teal walls, I left ordinary time behind and entered sacred time.

For the next two weeks, as if in a reverie, I watched bees buzz in the climbing roses and stared at clouds billowing through changing skies as words poured out freehand into spiral notebooks and digitally onto my laptop. Gazing over the Tomales estuary, where wilderness and civilization meet, I left the chores and interruptions of my daily life in Mill Valley far behind. In two weeks, I wrote the final two chapters of Knocking on Heaven’s Door: The Path to a Better Way of Death, which, in 2013, became a New York Times best-seller and Notable Book of the Year. Whenever I momentarily lost faith, I would go to the downstairs bathroom and read a framed incantation by the environmental writer Terry Tempest Williams called, “Why I Write.”

“I write to make peace with the things I cannot control,” it begins. “I write to create fabric in a world that often appears black and white. I write to discover. I write to uncover. I write to meet my ghosts…” I would read on to its final line, encouraging me to be as brave, gentle and truthful as I possibly could: “…I write as though I am whispering in the ear of the one I love.” Then I’d climb back upstairs to my bedroom-cum-workspace in the Tower Room and write some more.

The Realization of a Dream

The Refuge is the fulfillment of a dream long held by Peter Barnes, a former Newsweek journalist, serial entrepreneur (Working Assets mutual funds/Credo mobile) and socially committed venture philanthropist. He had fallen in love with West Marin in his 20s, when he worked on an early book at a 100-acre, semiderelict ranch he’d rented within Point Reyes National Seashore. (The rancher had a heart attack and was forced to move to Petaluma.) If he ever became rich, Barnes decided, after a stay at another philanthropically funded writers’ retreat, he would create a place where undernourished writers could work in the creative solitude, isolation and wild beauty of West Marin. “I vowed that if I was ever in a position to give back to the universe, I’d like to do something like this,” he says. His dream unexpectedly came true in the mid-1990s, after he sold his stake in Credo, which had by then morphed into a socially conscious financial services, credit card and telecommunications company. With some of the proceeds, he bought the Francis house next door to his own home. Then, with Fernandez’ help, he picked out saturated colors to replace the stark whiteness of the original walls, and scoured antique and second-hand stores for furnishings. “Nothing is new, it’s all sort of second hand, and there’s no plan to it,” he says. “I didn’t want it to look like everything came from Crate and Barrel.” In 1997, the Refuge opened its doors to its first writers.

“I cannot explain why the magic works, but it does,” Barnes continues. “It’s the beauty of the site, the wetlands below, the tide coming in and out twice a day. There are a lot of ‘edges’ around Mesa Refuge: the edge of the San Andreas Fault, the edge between civilization and wilderness, the edge between land and water. You see something and feel something that is beyond civilization, but you’re not so far away that you can’t capture it and put it into words.” Barnes funded the place completely at first. Then came the financial downturn of 2000 and the crash of 2008. “I naively thought I could finance it all by myself, because I hate fundraising,” he recalls. “I was wrong.”

For several years, the Refuge teetered on the edge of financial survival and was forced to curtail some residencies. Since executive director Susan Tillett took the reins in 2013, it has broadened its donor base and strengthened the board of directors, which currently includes internationally known cheese maker Sue Conley, the visionary cofounder of Cowgirl Creamery. Barnes, now 79, still contributes but is not a major donor. The Refuge owns its building, but the freestanding nonprofit has no endowment. It raises its yearly $350,00 operating budget entirely from donations, and it remains relatively unknown in the eastern part of the county. “A spirit of generosity permeates the entire Refuge,” says Tillett. “To be given that gift of time, space and support is really life changing for people. Many writers’ residencies are more oriented toward pure art, but we focus on the pressing issues of our time.”

All rested in precarious balance, and then in 2020 came an unexpected disaster. A contractor replacing weather-beaten siding uncovered leaks and dry rot beneath, and then a termite infestation. The more of the structure he opened up, the more damage he found. Major repairs began at once, and the Refuge was forced to take out a big construction loan. Last winter, the severely damaged Tower Room, where I had so happily stayed, was entirely rebuilt. Donors, including patrons and hundreds of former Mesa Refuge writer-residents, have so far rallied and contributed more than $160,000 toward the $500,000 needed to retire the loan and make the house safe and livable again before the onset of the rainy season — to waterproof and repair the structure, replace worn-out windows and electrical systems, update the kitchen and bathrooms, and replant the English garden with native plants better suited to aridity and climate change. If all goes well this fall and winter, the Refuge will open its refurbished doors in early 2022, welcoming a new crop of writers who will hopefully change our world for the better in ways we can’t yet imagine.

For more on Better:

- How to Protect Your Home from Wildfires: Home Hardening, Retrofits and Getting Wildfire Ready

- Community Heroes on Alert: Acknowledging The Brave Firefighters of Mill Valley

- When the Headlands Had Warheads: Reconciling Marin’s Nuclear Past While Looking to the Future

Katy Butler is a past finalist for a National Magazine Award and author of Knocking on Heaven’s Door and The Art of Dying Well. Her writing has appeared in the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Vogue and Best American Essays. A former reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle, she lives in Mill Valley with her husband, Brian Donohue.