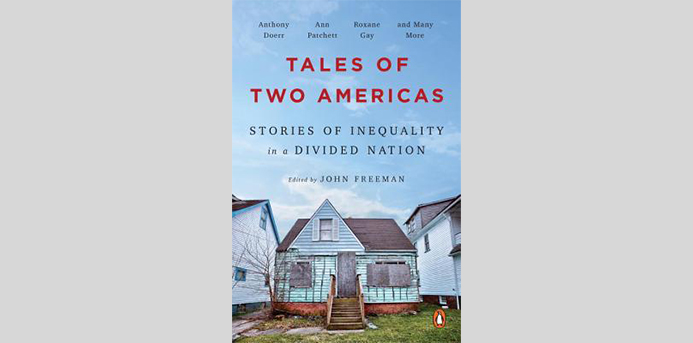

As part of this spring’s Chicago Humanities Festival, writer and literary critic John Freeman and journalist Sarah Smarsh met to discuss their shared concerns about income inequality in the United States. Smarsh recently contributed to an anthology on the topic, “Tales of Two Americas: Stories of Inequality in a Divided State,” of which Freeman was editor.

1. Our Stories Are Necessary for Change

Freeman opened the program by citing a fact from an Oxfam International report: “The 85 richest people in the world have as much wealth as the 3.5 billion poorest.” It’s a sad and sobering statistic; one of many that indicate a global issue that is increasingly evident in our country.

“If you’re in the top 5 percent of income earners, you’ve seen your wealth go up; but if you’re in an other category, you’ve seen it go down,” says Freeman. Everyone has their own story of rising or falling fortunes, and Freeman says, “These stories are necessary to turn those experiences into change.”

Smarsh, who is a regular columnist for award-winning public radio conversation and podcast On Being, is a wonderful interpreter of these types of American stories, describing herself as a having “dual-class citizenship” due to her low-income farm upbringing and current position as a tenured professor. She’s written extensively about class as a journalist but experienced a shift about five years ago, when it felt right to merge storytelling with research. “The moment I decided to draw on personal stories was the moment people started paying attention to what I had to say,” Smarsh says.

She adds that she finds the discourse around the topic of poverty in America “dangerously removed.” Discussions often happen between people with no firsthand experience or knowledge of the disadvantaged. Her goal is to humanize people who are represented as statistics. It’s imperative that we share our stories and, more importantly, listen to other’s experiences.

2. Poverty Affects the Body

Freeman comments on the intensity of physical labor that’s often required of lower classes to pay their bills. Smarsh grew up working on the farm with the hogs and the wheat harvest and now she gets paid to think and write. She says, “There’s a beauty in working with your body but, by and large, I physically benefit from my job now.” Like many Americans, her female family members work as cooks or in retail — jobs that require them to be on their feet all day and result in ailments specific to those demands, just as farmers often suffer from skin cancer because of their trade.

One particularly moving and memorable narrative of the physicality of poverty is found in an essay titled “Blood Brother” from Smarsh’s forthcoming book, “In the Red.” She tells the story of her brother’s participation in the plasma-for-money industry. She describes the open holes in her brother’s arms as “a blood tap like an oil well for draining, twice a week for almost 10 years” and how “the smallest elderly women sometimes put on extra clothes and ankle weights to meet the 110-pound weight limit.”

Each puncture offers fatigue, dizziness, bruising, the potential for infection and $50. Smarsh says, “My brother is giving an actual piece of his body. Women sell their hair for extensions and even organ donation has become complicated. Poor people’s bodies are being harvested for their parts.”

3. Categories Aren’t Discrete or Finite

Though the anthology references “two” Americas, it quickly becomes clear that the lines drawn between these groups aren’t clean and clear. We can always point to someone who has less or more than we do. Wealth is comparative.

And our particular category may change several times throughout our lives. Freeman grew up in a middle-class family and now has an apartment in New York City (no small feat) and a steady job, while his brother has been on public assistance and homeless at times.

Meanwhile, Smarsh grew up on assisted lunches and saw her father traveling to four states to find construction work after a job loss, eventually working alongside migrant laborers. She says, “None of my family thought of ourselves as poor though we were living below the poverty line. We were so removed from the faction of society where pecking order and wealth were even a consideration.” And, now, as a home-owner and professor, Smarsh says that she still carries that construction site with her every day. “You hold all of those experiences simultaneously,” she says.

The quintessential “American Dream” offers the idea that achievement is a means to wealth and happiness. But Smarsh asserts that “pulling yourself up by your bootstraps to create a life and earning that is commensurate with your efforts is just no longer true.” The dream has become a myth.

Find Sarah Smarsh on Twitter @Sarah_Smarsh and John Freeman @FreemanReads

More from Make It Better:

- Marie Kondo: How to Change Your Life Through Tidying

- How Can You Be Sure Your Family’s Drinking Water is Safe?

- Local Author Pens Memoir Chronicling Eating Disorders and Recovery

Pamela Rothbard is a writer and photographer living in Glencoe, Illinois. Her work has appeared in various literary and mainstream magazines and on National Public Radio and her parenting and baking blog, Flour on the Floor, was featured in Better Homes and Gardens. Pamela has been a regular Make It Better contributor since 2013. When she’s not behind a keyboard or a camera, she’s trying new recipes and restaurants and adding another layer of clothing because she’s always cold. Find her on Twitter and Instagram @pamelarothbard.

Pamela Rothbard is a writer and photographer living in Glencoe, Illinois. Her work has appeared in various literary and mainstream magazines and on National Public Radio and her parenting and baking blog, Flour on the Floor, was featured in Better Homes and Gardens. Pamela has been a regular Make It Better contributor since 2013. When she’s not behind a keyboard or a camera, she’s trying new recipes and restaurants and adding another layer of clothing because she’s always cold. Find her on Twitter and Instagram @pamelarothbard.