In the early 1940s, no one could have suspected that a quiet corner of Marin County would soon become home to the United States’ first racially integrated summer camp west of the Mississippi River. This is the story of the quarter-century long history of Forest Farm, where the Gregg family worked to bring progressive education ideals to a sunny knoll in the hills of West Marin, in one local example of what white allyship looked like in a segregated America.

Some people know this site as the location of Jerry Garcia’s death in 1995 — a residential rehabilitation center called Serenity Knolls now occupies the place where Forest Farm was founded in 1945. What is less known, is that a radical, progressive dream of husband and wife duo Harold and Frances Gregg thrived here for 25 years under their bold leadership.

Harold’s education at Columbia University’s Teachers College, and the family’s subsequent move to Suffern, New York — where they lived at what is now seen as the United States’ first community land trust — heavily informed their outlook and ideals. The Greggs — Harold, Francis, and their four young daughters Linda, Chloe, Susan and Louise — lived at Suffern with a cohort of other educators from the Teachers College. Frances, an English teacher herself, recalled later how the couple and their friends honed a vision of a country school where “children of all nationalities would live and learn each others’ customs and ideas through the arts, through crafts, nature, music and dance.” In these late night salons during the first few years of World War II, the Greggs and their peers positioned themselves as diametrically opposed to everything that Hitler and his Nazi party stood for.

When the Greggs returned to their native California in 1943 with a school on their minds, a home purchase in San Anselmo gone awry and a spirit of adventure landed them in what is now Samuel P. Taylor Park — at a time when the land had yet to be protected, and was in a state of ownership limbo. There, the family built a makeshift camp under the redwoods for a summer, until a chance encounter with a colorful landowner brought a property on Tamal Road in Forest Knolls into Harold’s sights, and brought their dream of creating a school into the realm of possibility. The existing summer home was enough for their family, but the property had only that house and an old barn. It would take some doing to create the facilities that they would need to operate a residential school, and building in the midst of World War II was no easy feat with all available materials going to the war effort. They decided instead to create a summer camp.

In early 1945, Harold had a lead on repurposed lumber from structures at Tanforan racetrack in San Bruno, which had tragically, and ironically — given the family’s purposes — been used as a temporary internment camp for nearly 8,000 Japanese Americans just a few years earlier. Each day for a time after his work at the county planning office, Harold visited the racetrack with a rented semi truck, then brought the used lumber back up Tamal Road and the steep driveway. Unable to brake for fear of stalling the weak engine, he sounded the horn at the foot of the hill, and relied on his daughters to swing the gate open for the speeding truck. The family then unloaded the wood together, and Susan spent evenings removing and straightening nails from the lumber, which Harold used in constructing the platforms for the camp’s first tents.

Next, Harold and Frances set about interviewing counselors for their first summer in operation. This summer, and for the next 24 years, they recruited undergraduate, graduate and doctoral students from UC Berkeley, Stanford, San Francisco State and University of the Pacific who they felt would be good matches for their multicultural program, regardless of, and more often informed by, their ethnicity and cultural background. Seventy years later, in 2021, daughter Susan Gregg Conard recalls the diversity of camp staff over the years: counselors of Native American, African American, Asian American and South Asian descent. The camp’s first year was nearly a decade before the landmark Supreme Court ruling Brown v. Board of Education, and two years before California’s Westminster School District v. Mendez ruled to eliminate segregation of Asian American and Native American students from white students here. Early on, Forest Farm campers were predominantly white, but many Jewish — this at a time when anti-Semitism was nearly as prevalent as racism in the United States. Over time, campers became more diverse as word of the camp’s inclusivity spread.

Once the logistics of bringing the camp to life were somewhat sorted out, there were still other issues to be resolved. Some neighbors feared noisy children and increased traffic up the country roads. Some bristled at the Greggs’ forward-thinking attitudes around race. We must remember that at this time, Marin County, like the rest of the United States, still had legal discriminatory policies at most levels of local governance. Policies like restrictive real estate covenants and ‘whites only’ bylaws at private clubs were in place to keep communities the way they had been since the subdividing of Marin ranches began in the early 1900s: white.

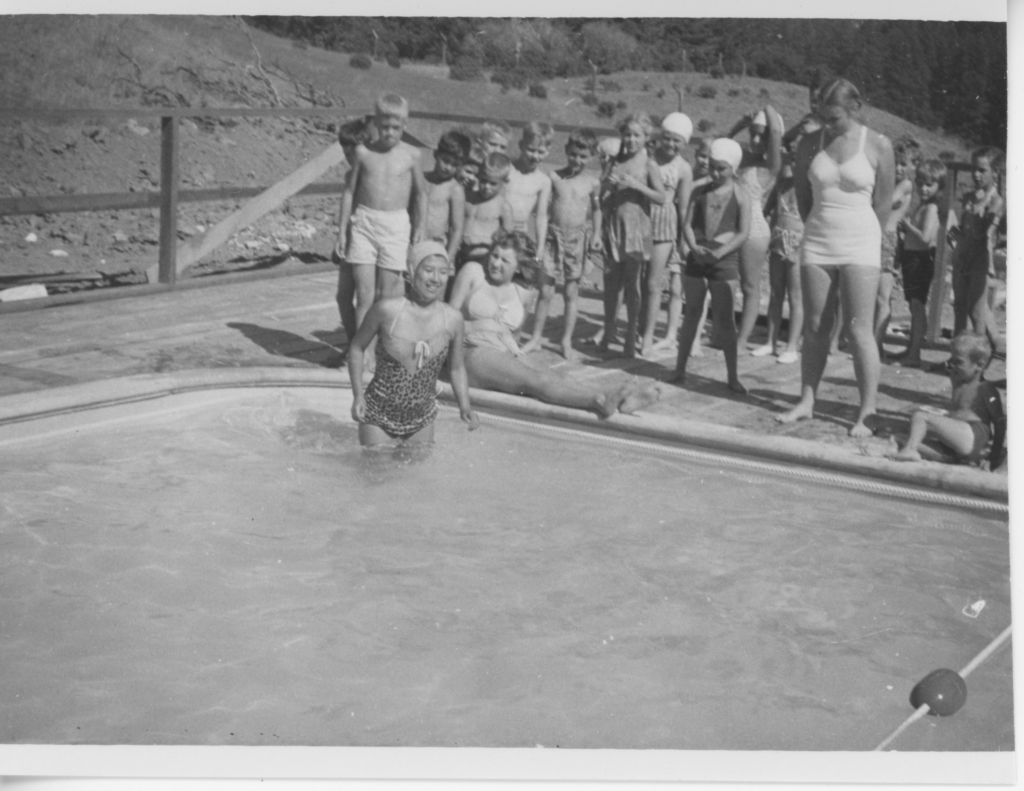

The contrast between these policies and Forest Farm’s ethos came into stark relief during the camp’s second summer in 1946, when what was supposed to be a routine outing to a local pool sent a shockwave through the camp community. As Frances Gregg recalled in her memoir, a young Chinese American counselor and UC Berkeley student brought her group of five and six-year-olds to the Woodacre Improvement Club for a morning swim. The pool attendant, following the club’s policy, denied her entry beyond the pool gate, but allowed her white campers in, leaving her to watch from the other side of the chain link fence, where Harold found her distraught, and in tears. A 1948 copy of the Woodacre Improvement Club’s constitution and bylaws shows that the club did not change their policy, despite an article in the San Francisco Chronicle by famed journalist Herb Caen penned shortly after the incident in 1946, putting the word out across the Bay Area that the improvement club did have this policy and had enforced it, too. Remarkably, Harold and Frances brought the situation to a vote with their young campers, and by far the most popular solution was for Forest Farm to build a pool of their own. They did, and Gloria was the first to enter it. The improvement club incident could have happened in any number of places around the country at this point in American history, but sometimes we forget that Marin County was not immune from these kinds of segregation that were entirely legal at the time.

Suspicion with the activities at Forest Farm was not just local, but they garnered federal attention in the late 1940s — at the peak of the McCarthy era. One summer day when camp was in session, five dark-suited FBI agents walked the dirt road from the camp parking lot to the commons up the hill. They had come looking for Harold. Frances led the men to Harold’s office in the converted barn. Without explanation, they cuffed Harold, placed him under arrest and led him back down the driveway to their vehicle, as campers looked on in shock. What could this rural educator have done to provoke such fear in Washington? Harold had caught their attention by writing about the camp and the fact that it was integrated in an updated version of his doctoral dissertation, which had become a popular textbook in public schools nationwide, Art for the Schools of America. The family learned that he was suspected of being a communist, and of indoctrinating his campers — now about 50 or 60 per summer — with his radical beliefs. Five days later, Harold was released, after no actual evidence of any seditious activity could be found.

Through all this, the family remained committed to their values. In the early 1960s, when a married Black man and white woman hoped to put down roots in the San Geronimo Valley, the Greggs sold a home originally intended for family to the young couple. What is unclear is whether real estate agents had refused to sell to the couple, or whether the fact that the couple had known the Greggs had just happened to lead them to the home. What is known is that some realtors in Marin at that time would still neither sell to people of color nor mixed race couples, despite laws outlawing the restrictive covenants of the past.

Harold and Frances Gregg did not seek recognition for their social justice efforts during their lifetimes, but their activism did impact the hundreds of children who attended Forest Farm in its 25 years of existence, the dozens of staff they employed from around the country and around the world, and those who discovered the San Geronimo Valley through the camp and went on to serve the community here. In this age of racial reawakening, the Gregg family can serve as an example of how small, committed groups of individuals with vision and drive can create new pathways forward. In Marin County, we can honor the Greggs’ progressive spirit by doing as they did at Forest Farm — putting ideals into action.

For More on Forest Farm:

- Facebook group for alumni and others connected with Forest Farm

- More photographs from the San Geronimo Valley

- A photo story from the San Geronimo Valley Historical Society about the camp

- An article about Harold Gregg from the Marin Conservation League

More from Better:

Owen Clapp is a writer and musician from Woodacre, CA, and the founder of the San Geronimo Valley Historical Society – a partnership with the San Geronimo Valley Community Center. His local history book “Images of America: San Geronimo Valley” was released in August 2019. Owen works with the San Geronimo Valley Affordable Housing Association, the Lagunitas School District, and the San Geronimo Valley Community Center in various roles. Recent projects include oral history interviews with West Marin residents for the Anne T. Kent California Room at Marin County Free Library, and a suite of songs written for San Geronimo Valley landscapes.

Owen Clapp is a writer and musician from Woodacre, CA, and the founder of the San Geronimo Valley Historical Society – a partnership with the San Geronimo Valley Community Center. His local history book “Images of America: San Geronimo Valley” was released in August 2019. Owen works with the San Geronimo Valley Affordable Housing Association, the Lagunitas School District, and the San Geronimo Valley Community Center in various roles. Recent projects include oral history interviews with West Marin residents for the Anne T. Kent California Room at Marin County Free Library, and a suite of songs written for San Geronimo Valley landscapes.