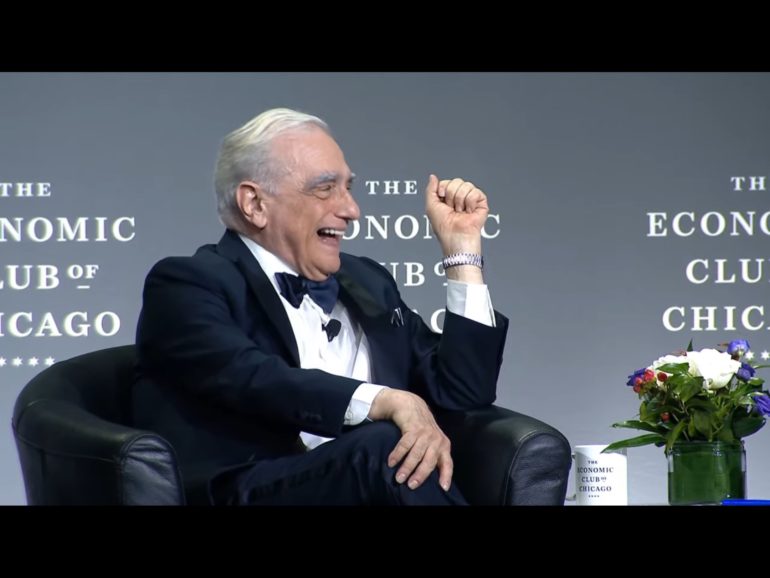

On Oct. 10, two titans of American cinema — Martin Scorsese and Jeffrey Katzenberg took the stage at The Economic Club of Chicago for a fascinating discussion about Scorsese’s storied career and his mission to protect and preserve motion picture history through his foundation.

If you’ve been watching movies over the past 40 years, you’ve probably seen at least a few films directed, produced or written by Scorsese. From Mean Streets and Raging Bull to Casino, The Departed and The Irishman, his body of work is equally stunning in both quality and quantity.

Though Katzenberg, as a producer and media proprietor, is frequently behind the scenes, his work is integral to American popular culture. As Chairman of Walt Disney Studios and later co-founder and CEO of DreamWorks Animation, he was responsible for movies such as Good Morning, Vietnam and The Lion King, as well as television series including Home Improvement and Golden Girls. He currently serves on several boards, including The Motion Picture and Television Fund, The Museum of the Moving Image, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, California Institute of the Arts, and The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research.

Scorsese Reflects on His New York Upbringing and Its Influence on His Films

The evening started with Scorsese reminiscing about his childhood in New York, and how his love of movies began.

“We were poor,” remembers Scorsese, and “at three years old, I had my tonsils out. Next thing you know, I got asthma and almost died. From that point on, they coddled me. The put me in a room; I couldn’t run, and I certainly couldn’t play with other kids. There was nothing I could do besides music and movies. So, from 1946 to 56, I was sharing these extraordinary emotions, with either my father or my brother, who were taking me to movies, which were my place of respite.

“We were living in a very small apartment, and it was a very rough area, mired in organized crime. Different crime families lived on different blocks. And there were stories, things you didn’t see on the screen.”

After Scorsese went to New York University, he started making films, and during his early years, Chicago proved pivotal to his career trajectory. “Chicago has a very important place in my life,” Scorsese said. “Back in 1967, Michael Kutzka’s Chicago Film Festival was where I showed my first attempt at a feature, I Call First. Film critic Roger Ebert gave it a rave review.”

I looked up that Ebert review of I Call First, and the famous Chicago film critic had said that this movie of Scorsese’s “is absolutely genuine, artistically satisfying and technically comparable to the best films being made anywhere. I have no reservations in describing it as a great moment in American movies.”

Now, that is the kind of review any young filmmaker would treasure.

The connection between Scorsese and Ebert runs deep. “Roger was Irish Catholic, and I’m Sicilian Catholic,” says Scorsese. “He wrote something about The Departed, and it just stuck with me. He said, ‘I’ve often thought many of Scorsese’s critics and admirers don’t realize how deeply the Catholic Church could burrow into the subconscious, how many ways Catholicism in his films is so important.’

Scorsese was deeply influenced by a Father Francis, who lived in the area around New York’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral. Father Francis gave Scorsese books – Graham Green, Dwight McDonald, James Joyce – showing the young artist that there were ways out of the poverty and crime of his childhood, telling him “You don’t have to live like this.”

Katzenberg mentioned that Mean Streets was obviously influenced by early experiences in New York’s Little Italy, which prompted Scorsese to remark that since he made that early film, “I don’t think I’ve ever sat down and watched Mean Streets from beginning to end again. It’s too hard. The story was based on a real thing. I had got out of a car with my friend in the morning, and we just missed the bullets. The car got shot up at Astor Place, over some stupid macho argument with this psycho, Crazy Butch. And I said to myself, the next morning, ‘This is ridiculous. We’re living on borrowed time.’ I was at NYU, and I’m wondering ‘What the hell is this all about?’ And then a friend of ours died at 16. I looked around and said, ‘There must be something more to life than this madness, where there’s no more talking and you’re arguing over nothing.’ That, I thought, is where the film — Mean Streets — should begin.”

And Mean Streets was where the film career of Martin Scorsese took off; in the next three years, he created Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore and the iconic Taxi Driver.

When Movie Magic Happens

About mid-way through the interview, Katzenberg said to Scorsese, “You’ve made 27 feature films, 16 documentaries, 7 TV shows, 7 short films, 2 music videos, and 8 commercials, which adds up to 67. So, when you’re making a film, is there a moment when you can tell that movie magic is happening?”

After thinking for a second or two, Scorsese said, “At the age of 13, 14, I was immersed in the films of Elia Kazan – On the Waterfront, A Face in the Crowd – and I thought ‘My god. Imagine being on the set when magic like that happens between actors, because it’s not a film anymore. It’s not theater. It becomes a kind of universal truth.’”

Scorsese mentioned two incidents, among many, when he could feel *the magic* on the movie set. In Mean Streets, for instance, there’s a memorable scene with Harvey Keitel and Robert De Niro in the backroom of a dive bar. De Niro is trying to convince Keitel that, swear to god, he’s going to pay off his debts.

“It was a three-and-a-half minute take,” remembers Scorsese, “that Bob insisted upon doing, and we squeezed it in on the last day of shooting. The improv suddenly came alive.

“Then years later, we’re doing Irishman with De Niro and Al Pacino, and there’s this incredible scene with the two of them where they’re at this big event, and Bob must tell Al – Jimmy Hoffa – that he’s got to end it all and give up the union. Al says, ‘They wouldn’t dare, they wouldn’t dare…This is my union.’ This scene shows the depth of the universe. And that was just two takes, and then the crew comes around and says, ‘That was something wasn’t it?’ Sometimes magic happens that way.”

In The Wolf of Wall Street, Leonardo DiCaprio and Matthew McConaughey are having lunch in a swank New York restaurant, and McConaughey starts humming deeply and beating his chest. It’s a little strange. After a few takes, Scorsese remembers, “I’m on the monitor, and Leo comes in and goes, ‘He (McConaughy) is doing something. He does these sounds. I don’t know what the hell it is. They’re like, weird.’ So, I ask Leo what he wants me to do, and he says ‘Let’s put it in.’ So, okay, we go up to Matt, and I ask, “Those things you’re doing. Do you think you can incorporate that? He said, “Well, those are just my vocal exercises.” And then the scene took off. And it was one of those magic moments where everybody just looked at each other and said, ‘Oh, my god.’”

Scorsese could talk about movie magic all night, and many of us would have been glad to have heard even more.

The Film Foundation: Keeping Movie Memories Alive

“Movies touch our hearts, awaken our vision, and change the way we see things,” Scorsese has said. “They take us to other places. They open doors and minds. Movies are the memories of our lifetime. We need to keep them alive.”

To keep alive those movie memories that mean so much to us, Scorsese founded and now chairs The Film Foundation, a nonprofit organization established in 1990 and dedicated to protecting and preserving the motion pictures that people around the world have come to cherish.

Working in partnership with archives and studios, The Film Foundation has helped to restore over 925 films, all of which are accessible to the public through programming at festivals, museums, and educational institutions across the globe.

“I learned in the mid-70s, when I went out to Los Angeles,” remembers Scorsese, “that many great films had been neglected to the point where the color was fading. That’s one of the reasons we did Raging Bull in black and white: the color was fading on all the color films. And at that point, they said, ‘You have to make all the films in color.’ So, I said to them, ‘I’m killing myself telling your story with colors, and in six to seven years, the colors will be gone. What the hell! We’ll do it in black and white.’ That was a big issue. And what eventually happened was that I called together filmmakers around the world for a protest about color fading… because we must keep these films alive.”

Now, The Film Foundation has established the Screening Room for these restored films, and they’re free to view online. This month it’s One-Eyed Jacks, which Scorsese says is “the only film Marlon Brando directed, and it’s a beautiful restoration.”

When he first founded The Film Foundation, Scorsese started working on the preservation of, as he says, “the bigger ones like Lawrence of Arabia, Spartacus and Bridge on the River Kwai. The big thing now is the World Cinema Project,” Scorsese continued, “an organization that pushes to restore films from around the world, from countries that don’t have the facilities to preserve the films themselves. We’re talking about Mali, Indonesia, India and the African countries. We’ve restored almost 40 films.”

The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project has restored films from 28 countries, and their free educational curriculum, The Story of Movies, teaches young people – over 10 million to date – about film language and history. Throughout his career as a movie maker, Scorsese has created movies we love while bringing to our attention not only foreign films we may never have heard of, but old movies that, without the care and attention from organizations like The Film Foundation, would be lost forever.

How to Help:

Support Scorsese’s mission to protect and preserve motion picture history by donating to The Film Foundation.

More from Better:

- Double Your Contribution: Support Access to Cinematic Storytelling With The Chicago International Film Festival

- How Chef Rick Bayless Is Cooking Up Change Beyond the Kitchen

- The Grand Hotel on Mackinac Island Blends Old-World Charm With Contemporary Luxury for a Sustainable Escape to a Bygone Era

David Hammond is Dining and Drinking Editor at Newcity and contributes to the Chicago Tribune and other publications. In 2004, he co-founded LTHForum.com, the 15,000 member food chat site; for several years he wrote weekly “Food Detective” columns in the Chicago Sun-Times; he writes weekly food columns for Wednesday Journal. He has written extensively about the culinary traditions of Mexico and Southeast Asia and contributed several chapters to “Street Food Around the World.”

David is a supporter of S.A.C.R.E.D., Saving Agave for Culture, Recreation, Education and Development, an organization founded by Chicagoan Lou Bank and dedicated to increasing awareness of agave distillates and ensuring that the benefits of that awareness flow to the villages of Oaxaca, Mexico. Currently, S.A.C.R.E.D is funding the development of agave farms, a library and water preservation systems for the community of Santa Catarina Minas, Oaxaca.