Schools should be places that nourish dreams, not destroy them. Yet, on April 16, 2007, the unimaginable happened once again.

It was another school shooting, this time on the campus of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (Virginia Tech). The first shooting was in a dormitory, then two and a half hours later in classrooms and hallways. The shootings by 23-year-old undergrad Seung-Hui Cho, armed with two semi-automatic pistols — both purchased legally — left five faculty members and 27 students dead or dying before turning the gun on himself as police closed in.

Authorities found 203 remaining rounds of ammunition in the Norris Hall classroom next to his body. Cho’s gunshots wounded seventeen others, and six more were injured when they jumped from a second-story window to safety. His choice of 9mm hollow-point bullets increased the severity of the injuries.

While April 16 was a day of many tragedies, many recall the acts of heroism in the gut-wrenching testimonials of the survivors. In room 211, where Intermediate French had been interrupted by the sound of gunfire, Professor Jocelyne Couture-Nowak and student Henry Lee barricaded the door with desks. Professor Couture-Nowak yelled at students to get under their desks and call 9-1-1. Cho pushed through the barricade and killed Professor Couture-Nowak and Lee. Air Force ROTC member Matthew La Porte then charged toward Cho, but seven bullets ended his life. Of the 18 students in the class at the time of the shooting, 11 died and six others were wounded.

In room 204, Professor Liviu Librescu, a Holocaust survivor from Romania, used his body to keep the door to his room closed long enough for most of his students to jump out of the second-floor classroom windows to safety before being shot through the door. When Cho finally made it into the classroom, he fatally shot Professor Librescu and student Minal Panchal.

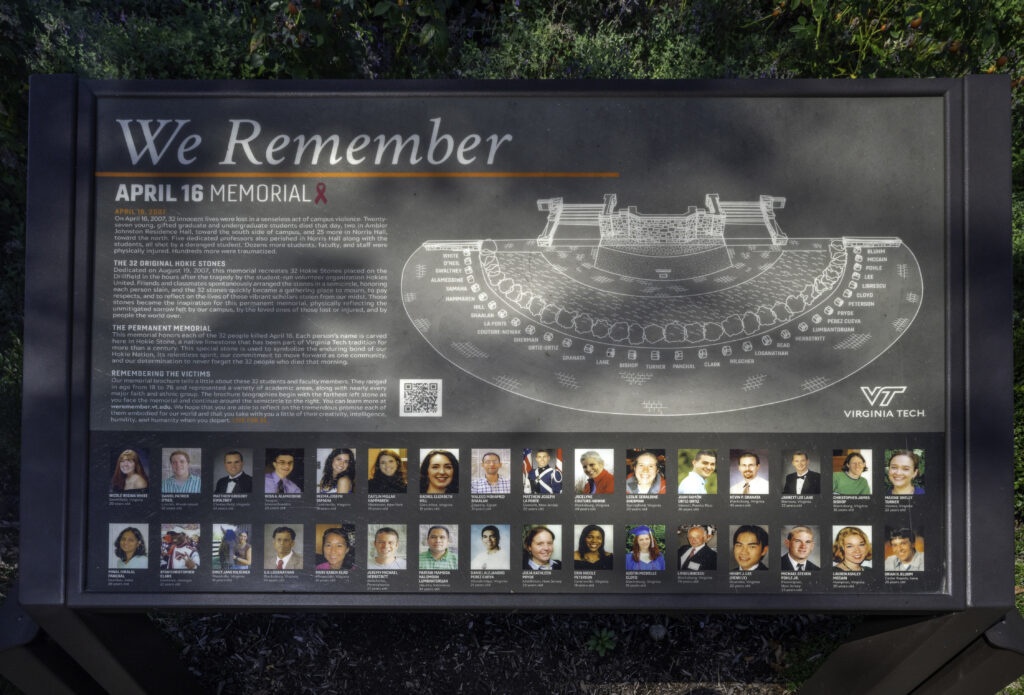

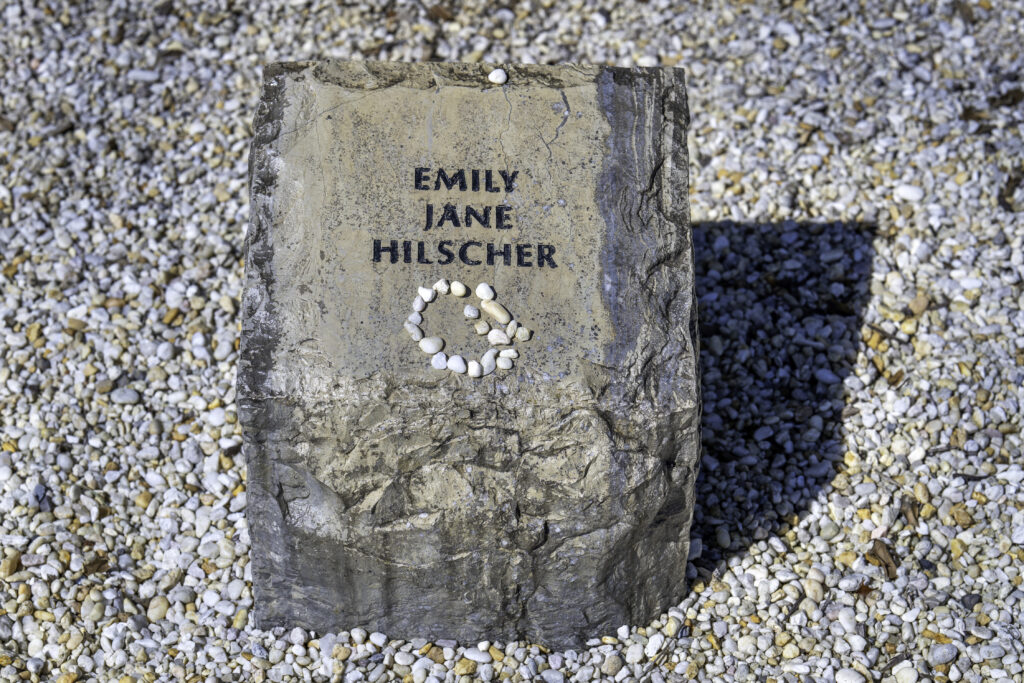

In the hours, days, and nights following the shooting rampage, makeshift memorials and vigils for those killed or injured began appearing on campus. Members of Hokies United, an alliance of student organizations, placed thirty-two pieces of Hokie Stone, each labeled with the name of a victim, in a semicircle in front of the Drillfield viewing stand. This makeshift memorial became the model for the permanent April 16 Memorial. The memorial features a larger center stone engraved with the message, “We are Virginia Tech. We will prevail,” from a poem penned by English professor Nikki Giovanni.

I interviewed Dr. James Hawdon of The Virginia Tech Center for Peace Studies and Violence Prevention after visiting the memorial to the victims of the deadliest school shooting in US History.

Mark Edward Harris: What’s the history behind the Center for Peace Studies and Violence Prevention?

James Hawdon: The Center was created after the tragedy here in 2007. It was a way to convert this space in Norris Hall, where there was unbearable suffering and tragedy, into something that could result in some pro-social outcomes. We act as the transdisciplinary hub for research, education, and outreach focused on the causes and consequences of violence and responses to violence.

MEH: What are some examples?

JH: I’m the lead on a project that’s looking at online hate and extremism and the consequences of how that leads to polarization and potentially radicalization and ultimately offline violence. We’re looking at factors that predict exposure to this environment and how people respond to it when they see it. We have collected data since 2013, including cross-national data, to analyze the similarities and dissimilarities across nations.

We have several areas of study in the Center that we refer to as hubs, with faculty members as hub coordinators. One of them is our cyber criminology lab, where we collect data on cybercrime victimization and perpetration. The data that is out there mostly focuses on victimization and cybersecurity issues, target hardening technological solutions like password protections and antivirus programs. We’re focused more on the human element of what leads to this.

We also have hubs on environment and justice, mediation and peace building, peace education, State violence, victims and victimization, and community recovery and resilience.

MEH: None of these have easy solutions.

JH: These issues are often complicated. For instance, there is a project analyzing how eradication efforts to wipe out the poppy supply in Afghanistan led to the spread of benzo dope throughout Western Europe. We get our students involved in the research and collecting data.

We also fund projects that integrate research, teaching, and outreach on a topic. For example, there’s a program in a neighboring rural county where the community organization was trying to work with the county to better deliver health and police services. They hired graduate students to help them collect data.

There’s another group collecting data on a local program that is trying to encourage the safe storage of firearms. While there are more guns than people in the country, the majority of households do not have a gun. It’s just that the people who have guns tend to have lots of them. But the vast majority of gun crimes are committed with illegally obtained weapons. That’s why safe storage techniques are so important. Based on research, the gun crime rate is substantially higher and significantly correlated with gun theft rates.

MEH: Does the Center have an official stance on high-capacity guns?

JH: As a unit within a State institution, we don’t take political stances. What we do is objectively and concisely as possible summarize the evidence on high-capacity guns. Evidence suggests that access to them certainly increases the number of victims in any shooting that occurs. The evidence about whether or not limiting access to them helps prevent these incidents is weak at best.

MEH: How do you share your findings?

JH: We disseminate our research findings through academic articles and make our data publicly available. Anybody can go to the Center’s web page and download most of our data sets. We also shared it with local police agencies, residents, and businesses in Virginia.

For example, e-commerce is a massive boon to the economy, but it has also exposed us all to a lot of threats. Our data shows that around 19% of people are engaged in some kind of cybercrime. On the hate side of it, about 19% of young adults (18–25) admit to posting it. The general cybercrime data is for the adult population, but our best data for hate is only among young adults.

MEH: Those are shocking percentages.

JH: Spend any time in forums where politics are being discussed, and you will frequently see in the comments some pretty nasty things being lobbed against groups and individuals.

MEH: What is considered hate speech?

JH: It’s anything that attacks a person or group because of their group’s characteristics. I can hate you and say all kinds of mean, nasty things to you because I don’t like you, because I thought you were hitting on my girlfriend, or you stole my lunch money, or something like that, and that would be cyberbullying. It becomes hate when I don’t know you at all, but I hate you because you’re a male, or because you’re white, or because of your religion, or politics. You’re a member of some group.

MEH: Where were you on April 16, 2007, when the attack in Norris Hall, now the location of the Center, took place?

JH: I was in my office in a neighboring building, McBryde Hall, on the sixth floor. I was able to see what was transpiring around Norris Hall. I witnessed students jumping from the windows to safety, SWAT teams getting in place, and eventually victims being carried out and students being escorted away by police and running to neighboring buildings.

MEH: Were students aware that there had been a shooting incident in a dorm before the shootings at Norris Hall?

JH: The initial murders were shortly after 7 AM at West Ambler Johnston Hall, but the campus-wide notification didn’t go out until around 9:42 AM, shortly after the shooting at Norris Hall had begun.

The task force that the Commonwealth of Virginia put together looked into the response in depth, but the short version of it is that when officers discovered the first victims in the dorm, the assumption was that it was a domestic dispute. They talked to fellow students who reported that the female victim’s boyfriend had been seen around campus and that he was a gun enthusiast, so they put out a bulletin to find that boyfriend. It took a while to find him, and when they did and questioned him and did a field test for gunpowder residue, it quickly became obvious he was not the murderer. They understandably but incorrectly went with a scenario in which they didn’t think the campus was facing a threat and that the threat had left campus.

MEH: And that connection was not made until after the mass shooting at Norris Hall. What has been learned going forward since the victims cannot be brought back?

JH: Mostly what we have learned has come from things that we’ve already known, that we’ve seen borne out in terms of how to handle these situations, not sitting back like what happened in Uvalde. That protocol is to engage with the shooter, and that protocol was put in place after Columbine. It remains the best way to approach these situations from a law enforcement response.

In terms of preventing these situations, it’s a tall task. One thing that became obvious after the Virginia Tech incident was the importance of sharing information and taking threats seriously. That has definitely changed in terms of how organizations, schools, and workplaces respond to their employees or students who appear to be in crisis.

MEH: Seung-Hui Cho’s past had a number of red flags, including two female students filing harassment reports with the campus police, sending a message about killing himself to his roommate, which led to him being transported to a psychiatric hospital, and writing disturbing essays in a creative writing program.

JH: The problem is that a lot of the stuff makes a ton of sense in hindsight. Once we have the correct framing of the event, we can look back at people’s behaviors and say, “We should have seen that coming. He wrote horrible, violent stories in a creative writing class.” But so does Stephen King. We simply can’t investigate every person who writes about violence. And indeed, many of these things are innocent. So, what we have to look for are integrated patterns. The assailant here showed those patterns. But the problem was that people didn’t talk to each other. They didn’t necessarily report it. So if we had his work from his classes, his mental health records, his roommate’s and classmates’ testimony about some of his behaviors, we probably would have said, “This kid is in a serious crisis.”

Some of that information is protected by FERPA (The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act) and HIPAA (The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act). We need to look out for each other, pay attention, and look for radical changes in behavior. The people who are in the best position to recognize radical behavior changes are parents, friends, classmates, teachers, and coworkers.

MEH: What can they do if they see potentially dangerous signs?

JH: In companies and schools that have anonymous tip lines, people show a willingness to report things when colleagues suddenly start acting in a concerning way. If you have to go to my boss and report me, and my boss knows that it’s you, you’re going to be hesitant to report me. Whereas, if it’s anonymous, the evidence says that you’re willing to say, “Hey, Jim’s acting a little strange lately.” Once that happens, the company or the school needs to be willing to respond to that.

To be sure, we have insufficient mental health facilities, and we also have to recognize our understanding of mental health is not overly impressive. The perfect example is Eric Harris of Columbine. He basically told mental health professionals what they wanted to hear. He wrote about that in his diaries. Our advances in medicine, be it for physical illness or mental illness, are remarkable, but there’s still so much we do not understand. We are always playing from behind. The perpetrator always has the advantage.

MEH: Especially when they’re armed with automatic and semi-automatic weapons.

JH: Red flag laws that would make it more difficult for people who are identified as being in crisis to potentially access guns are important, but it’s hard for us to prevent them from getting them. We need to recognize that there are so many guns available in the country. However, if we can slow the person down, give them a little bit of time for the crisis to resolve or for people to intervene, that could potentially help. We know that it certainly does with suicide.

MEH: The Center hosts workshops on conflict resolution, which can help prevent issues from escalating to violence.

JH: We host and co-sponsor workshops and speakers on various topics related to the causes and consequences of violence. Restorative justice is a conflict resolution technique that helps the people involved in a conflict resolve it in a way that they both find to be fair, working with a neutral third party. It requires a perpetrator to recognize his or her actions and the harm that they’ve caused. It also requires the victims to approach the perpetrator with a willingness to work toward an agreement and eventually forgive. We’re trying to get more students exposed to these techniques. Hopefully, as they move forward in their careers, they might be interested in getting formally certified as a mediator.

MEH: What are some other highlights about the Center?

JH: We do work looking at victimization, who is likely to be victimized, and how to prevent them from being victimized. One of the projects we have is looking at elder scams. Another project is looking at the importance of memorializing collective trauma.

I’ve been involved with some of this research, but it’s really one of my colleagues who is the lead on looking at how we memorialize collective trauma. We see that after acts of mass trauma, communities tend to come together. After 9/11, we were all New Yorkers for a little while. After here, the whole world was — our mascot being the Hokies — we were all Hokies. Even our rivals, UVA, claimed to be Hokies.

How does that emerge, and how is it sustained? Any collective that suffers a trauma is vulnerable. I observed that the people here in Blacksburg were deeply shaken. It shattered the notion that “It can’t happen here.” Tragedies often expose underlying problems in the community. For example, Katrina exposed the long-standing and deep racial divides in New Orleans. Those divides need to be addressed and hopefully healed.

MEH: At what point are those issues fully addressed?

JH: While people are still trying to find ways to cope, get adequate food, and trying to get back into their houses and schools back up and running, it isn’t the best time to try to heal long-standing divisions. It’s better to heal from that immediate trauma and then go into the harder discussions around what very well could have been the underlying causes of the trauma.

Our research has found — and what we try to make known to others who suffer these tragedies — that communities are comprised of three layers. There are the private networks — your friends and family. Then there are the parochial networks, local schools, local businesses, religious organizations, community clubs, and other things of that nature. Then there’s the public realm, the bureaucratic institutions of the town, the state, the police, the media.

Each of those has its role to play in recovery. If you lost a loved one, the healing comes largely from your family and friends. You need to be reassured that the group is going to be okay, that, while we recognize the loss, recognize what the person meant to the group, the group will continue, like we do with mourning death.

We found that people who participated in the parochial realm, who went to their club meetings, who went to their religious organizations, and who frequented local businesses did far better in terms of their physical and mental health outcomes than people who withdrew. So, after a mass tragedy, if at all possible, the rotary club and the gardening club shouldn’t cancel events. You’re tempted to, out of respect for the victims, but what we found is that these are chances to get together. Your gardening club is not going to talk about how to plant petunias; you’re going to talk about the event. That is a cathartic experience.

MEH: Has the April 16 Memorial been cathartic as well?

JH: I believe it has. Our memorial here basically replicated something that occurred spontaneously the night of the murders, and it became a focal point where people would lay flowers and write notes. So when it came time to make an official memorial, it was a pretty easy design decision. The only contention was that one student put out a 33rd stone, one for the assailant. The argument was that he was a member of our community. That did not go over well, and the stone was removed. We’re trying to understand how to present that history in a way that helps people. We know that memorials can help with healing.

MEH: In the case of the Virginia Tech shootings, you had innocent victims and one clearly defined perpetrator. Not all issues are so black and white.

JH: We also have to recognize that there’s a difference between healing and reconciliation. Internal forces and intra-group forces drive healing, whereas reconciliation is, by definition, an inter-group process. So healing is promoted by the group coming together and reaffirming itself, reaffirming its value, retaking control of the narrative, and basically supporting each other.

For example, take the case of lynching victims. Taking control of that narrative, which, of course, has been attempted for a long time now, dating back to Ida B. Wells’ work and similar efforts. Countering the narrative that these people were lynched because of crimes that they committed, when, in fact, a lot of them were falsely accused of crimes. Taking control of that narrative, reaffirming the value of the group, recognizing that harm has been done, and being there in support of each other. We recognize that these people were lost and taken from us and acknowledge them as valued members of the group who are now gone.

Now that’s a very different process than reconciliation, which is when the two groups come together. One group has to recognize its role in causing the trauma and own up to being the perpetrators. A good example of this is with the Holocaust, where the Germans have been pretty open about it. “Yes, we were the perpetrators. What we did was wrong.” And that is one of the most important steps in the process. But admitting that you are on the wrong side is difficult. In many conflicts, both sides claim to be right. A good example is the American Civil War.

MEH: It’s staggering to contemplate the loss of life in that four-year conflict.

JH: Seven hundred thousand Americans died. There was a lot of harm done, and the infrastructure of the South was devastated. So if I’m a Southerner and I say, “The war was our fault because of our insistence on slavery as an institution and perpetrating slavery as an institution was wrong,” that is me admitting that I’m the perpetrator. But what I have done is minimize the harm done to my group. If it’s my fault that the war happened, then all of the devastation of Sheridan’s march through the Shenandoah and Sherman’s march to the sea is because “I brought that on myself.” So my victimization has been weakened.

Conversely, if I say “It was the North’s fault for violating the constitutional agreement of States Rights, and this was the war of ‘Northern Aggression’, then I am recognized as the victim. If you flip that and I’m a Northerner and I say, “It was the war of Northern Aggression.” The hundreds of thousands of my comrades who ended up dead and all of those who were enslaved, I’m negating their victimhood. Whereas if I was doing this to preserve the Union and emancipate the slaves, to wrong a horrible evil, then my comrades’ victimhood and the salves’ victimhood have been recognized.

The problem often faced in reconciliation is getting the perpetrator and the victims to acknowledge what went on. That’s why you see things like South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, trying to get each side to recognize their roles. So healing and reconciling are two very different processes.

If the goal is reconciliation, the target audience is both groups, and the goal is to get one group to recognize its role as perpetrators and acknowledge the other as victims. It’s very similar to the different functions of a museum versus a memorial. A museum is supposed to teach us about what happened. To do that, you have to learn about the perpetrators and their motives.

For example 9/11, to understand why that happened, we have to understand the motives of the hijackers. We have to understand what could conceivably convince somebody to end their lives and to end the lives of 3,000 other people. We have to talk about the perpetrators and look at their stories. What led them to do this? That’s not what we should do when we’re memorializing the victims. A memorial is about healing and focused on the group that’s being memorialized rather than a mechanism of reconciliation.

Of course, when you’re talking about something that is all-consuming of the space like the Holocaust, the memorials have to be in the space where it happened, because it happened everywhere the Germans occupied.

MEH: When I was 19, I visited Dachau, and that memory will stay with me forever. Five years later, I completed my Master’s thesis on Boston’s historic sites and the interpretation methods used to convey their history. During my studies, I came to understand that one of the realities of the human condition is our proclivity for war. Will and Ariel Durant’s Lessons of History summed it up so succinctly, “War is one of the constants of history, and it has not diminished with civilization or democracy. In the last 3,421 years of recorded history, only 268 have seen no war. We have acknowledged war as, at present, the ultimate form of competition and natural selection in the human species.” The Durants wrote this in 1968, and since then, we have not added any years to the peace side of the equation.

JH: Yes, violence has always been with us, and undoubtedly always will be. But the good news is there’s a lot less of it now. If you look at the national level, contrary to the rhetoric that you might hear, crime rates are near record lows. If you go back in human history, we were frequently at war with each other, and wars frequently killed very large percentages of the population. Now, horrible as they are, we have rules of warfare.

Unfortunately, not all countries follow these, but more do than they used to. Think about the tactics of World War II. It was to purposely target civilians to break the will of the country. After World War II, we collectively came together and said, “Maybe we shouldn’t do that. Maybe we should have rules of engagement for when and who you can kill.” Obviously, those have been broken, but in the wars that followed, there tended to be far fewer civilian casualties. So while there is still too much violence, humans have become more civilized, and there are signs of hope.

MEH: Why is there violence at all?

JH: We are animals. Our instincts are to protect our group. We are tribal. When we think our pack is threatened, we will often respond however we can to protect it, and one of the forms of power is violence, and not only in a protective mode. Of course, there are those among us who are willing to use it as the primary means to win an argument.

MEH: Or land, resources, power… What can individuals do to help not only their pack but humanity at large?

JH: One thing that has led to the hope of civilizing human relations is expanding our definition of who’s in our pack. Also, we need to realize that economic issues should no longer be causing us problems. We produce way more than what everybody needs to live a comfortable life. But we need to expand the definition of the pack with whom we are willing to share our stuff and stop seeing each other as potential enemies. The more people with whom you feel empathy toward, the more people you’re going to look out for, and the more people who are going to look out for you. That is the hope. And there is evidence that we are doing that.

As a species, we are far more likely to be concerned about the suffering of people in far-away lands now than we were a hundred years ago. So, the empathy that we have when tragedy strikes those near us has extended to more people. For example, the horrible wildfires in Los Angeles, I think the vast majority of Americans are expressing empathy toward the people there at the moment. We need to figure out a way to sustain that. We’re all in their corner now, so why, in a few weeks from now, do we forget them? They’re still our fellow countrymen. They’re still our neighbors. They are still in need. So if we can expand our definition of the pack, then there’s hope.

MEH: In the bigger picture, the goal would be to expand it to all of humanity.

JH: That would be the ideal. That would be the way to truly reduce the atrocities that we do towards one another. I’m not a Utopian. I don’t think that’s going to happen anytime in the near future.

MEH: Unless we get invaded by another planet.

JH: Right. Unfortunately, one of the things that brings us together is being attacked. And it’s the conflict with a third party that brings two formally conflicting parties together. So we may need an alien invasion to unite humanity.

MEH: Nature somehow created us this way as it did with the rest of the animal kingdom.

JH: We all have survival instincts, which have allowed our species to survive. So if I perceive you as a threat, I’m faced with a choice: “Do I flee, or do I fight?” It is a fight or flight response; the response isn’t flight or help each other out.

MEH: Virginia Tech currently has more than 30,000 students, a few thousand more than at the time of the shootings. What does that say about resilience and human fortitude?

JH: I’ve talked about this to some students. Certainly not a representative sample, but a lot of the students think, “It could have happened anywhere.” If we try to avoid every place where there was a horrible event, it would limit our ability to move around.

MEH: What does the school do in addition to the memorial to remember the victims?

JH: The university holds a memorial service where the names of the 32 victims are read with a moment of silence at the time that the murders occurred. That night, there’s a candlelight vigil. There’s also a 3.2-mile run in remembrance of the 32 victims. It’s a day of remembrance and reflection.

How to Help

The Virginia Tech Center for Peace Studies and Violence Prevention is an academic and research organization whose vision builds on the cultural initiatives that evolved within the Virginia Tech community after the tragedy of April 16, 2007. Donations to the Center’s educational mission support cross-disciplinary work in violence prevention research, education, and hands-on learning experiences.

Assignments have taken award-winning photographer and Make It Better Foundation Director of Photography Mark Edward Harris to more than 100 countries on all seven continents. His books include Faces of the Twentieth Century: Master Photographers and Their Work, The Way of the Japanese Bath, Wanderlust, North Korea, South Korea, Inside Iran, The Travel Photo Essay: Describing A Journey Through Images and his latest, The People of the Forest — a book about orangutans. He proudly supports the Center for Great Apes, the Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation, and the Search Dog Foundation. You can find him on Instagram or his website.