After the tragedy, Marion Kahle wasn’t sure she even knew how to breathe.

Her world turned upside down on a summer day in 2005 when her son, Fritz, shot and killed a young woman outside of C.J. Arthur’s in Wilmette and then killed himself. For Kahle, it was the end of one part of her life; the part that included a son she loved.

“He was a wonderful boy and young man,” she says talking about her son. “But then he began having problems with jobs and relationships. He had problems being an adult.”

Kahle knew her son was troubled. He struggled with anger and anxiety for years—bar fights and altercations with an ex-girlfriend—but when his father died in 2004, Fritz’s distress grew. He cut ties with his mother and lost his job. “He refused to get help,” said Kahle, referring to this period of time when friends noticed his withdrawal and obvious pain.

Then a year and one week after his father’s death, Fritz shot and killed Candice Sepheri and wounded her 4-year-old daughter, Sholeh, outside the restaurant where Sepheri worked. Fritz then drove to Sepheri’s nearby house and shot himself. The murder/suicide shocked the North Shore and his mother. Fritz knew his victim; it wasn’t a random crime. She was the girlfriend of his longtime friend, Jason Falzer. But his motivations weren’t clear and his mother still wonders what happened and why.

Then a year and one week after his father’s death, Fritz shot and killed Candice Sepheri and wounded her 4-year-old daughter, Sholeh, outside the restaurant where Sepheri worked. Fritz then drove to Sepheri’s nearby house and shot himself. The murder/suicide shocked the North Shore and his mother. Fritz knew his victim; it wasn’t a random crime. She was the girlfriend of his longtime friend, Jason Falzer. But his motivations weren’t clear and his mother still wonders what happened and why.

“It’s often a cascading effect,” says Linda Rubinowitz, Ph.D., assistant clinical professor at Northwestern University, attempting to explain how someone becomes desperate enough to see suicide as an answer.

“Someone has a predisposition to depression or a trauma they haven’t dealt with. They withdraw from friends and family, and the cords of support begin to fray.”

She describes a downward spiral where eventually, the individual sees suicide as the only answer.

“It sounds obvious, but it often isn’t,” she adds. “Families feel terrible that they didn’t intervene or see a sign, but the person may be trying to hide his plan and may even seem better—calmer and less agitated— because they’ve made their decision.”

Kahle isn’t sure if she could have stopped her son’s violence. “There was no one thing or trigger that anyone was aware of,” she says. “Still, I have so many “what ifs” and “if onlys” to deal with.”

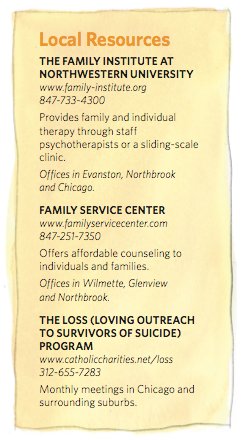

She has managed, however, to pick up the pieces of her life. She found her way to a program run by Catholic Charities, Loving Outreach to Survivors of Suicide (LOSS).

“They taught me how to breathe again,” she says “It was the one place I could go where people understood. They knew how it felt to lose someone in such a terrible way.”

Father Charles Rubey, who started the LOSS program 31 years ago and continues to run it, says that the monthly meetings provide a nurturing, non-judgmental environment where people can grieve their loss.

“Survivors feel there’s something wrong with them, that they’ve been a bad parent or a bad spouse if they lost someone to suicide,” he says. “We help them see that they’re not bad, they loved that person, and they’re grieving the loss.”Kahle credits time and the LOSS program with helping her come to terms with the way her son died and the sadness he left behind.

“There’s hope for survivors,” says Kahle, speaking of her journey. “You have to keep telling yourself that it’s not my fault, no matter how much you feel it is.”