Want to build a new $10 million center to treat the No. 1 killer of adults? Stabilize a world-class ballet company with annual revenue infusions in excess of $1.8 million? Raise millions to renovate the Great Hall at Lincoln Park Zoo? Develop a cutting-edge biomedical consortium between the University of Chicago, Northwestern University, and the University of Illinois Chicago? Purchase and renovate a $10 million music center? Start a local opera company that becomes an international standard-bearer — then raise $5 million in one night to celebrate its 50th anniversary? Call a Chicago woman.

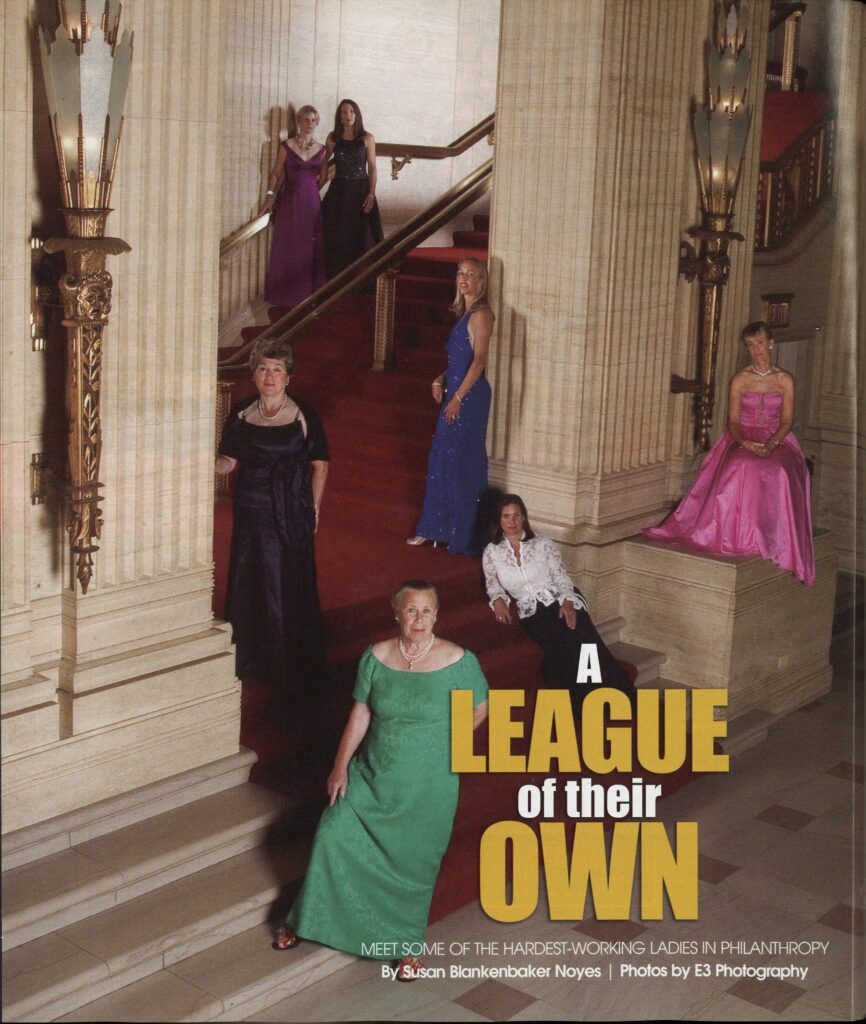

Because in the City of Big Shoulders, it’s the elegant, feminine figures who often take on the heaviest philanthropic lifting. Women’s boards — a powerful concept unique to the Chicago area — have been the institutional backbones of arts organizations, museums, zoos, and medical institutions for more than a century. Increasingly, women are taking on leadership roles elsewhere in Chicago’s billion-dollar world of philanthropy.

Those who closely watch Chicago’s philanthropic scene commonly believe that the overall health of a civic organization can best be measured by whether it has a women’s board — and the level of that board’s activity. One thing is clear: the more successful the women’s board, the more successful the organization overall.

A perfect example might be a conversation recently overheard at the Chicago History Museum’s annual Making History Awards. It was a gala as fine as any, honoring five of Chicago’s pillars of industry, sports, architecture, and service — the kind of gala that should have packed any ballroom in the city. But the percentage of empty chairs at the banquet tables was, well, embarrassing. So much so that a leading investment-firm chairman, a wise elder from Winnetka, commented to his tablemates, “It’s because they don’t have a women’s board.”

To truly understand the power of a women’s board, look to the Joffrey Ballet. The Joffrey moved here from New York City in 1994. Despite yeoman efforts by a prestigious board of trustees, it struggled financially for several years. Then it got smart — and started a women’s board.

“The Joffrey needed its profile raised, and nothing does that like the powerful women in this city,” explains founding trustee Maureen Dwyer Smith of Lake Forest. She and a few passionate friends launched the board in 2000. “The $1.8 million it raised last year made the women’s board the Joffrey’s largest donor,” Smith says. “Its more than 130 members are deeply committed to providing the ongoing support that will keep the Joffrey in Chicago forever.”

But perhaps no organization embodies the power of women’s civic strength, vision, and accomplishment better than the Lyric Opera of Chicago. The story of the women who gave Lyric its birth and helped it grow has become one of Chicago’s great legends. Lyric was born when visionary Carol Fox decided the city’s concert hall needed an opera company. Another powerhouse, Ardis Krainik, succeeded Fox as Lyric’s artistic director and broadened the opera’s support by charming one Chicago leader after another into joining its board. “Carol traveled to Italy to find star singers and made sure those performers were well-tended while they were here. Lyric still operates that way,” says Diane Mayer of Lake Forest, immediate past president of Lyric’s women’s board.

“The Lyric’s women’s board provides parties, education, and glamour that create great PR,” Mayer adds. “But more importantly, it also produces fundraising. The gala to celebrate Lyric’s 50th anniversary, chaired by Shirley Ryan and Charlotte Tieken, raised an unprecedented $5 million in one evening.”

The 120-year-old Women’s Board of Rush University Medical Center also flexes its philanthropic muscle. Its annual fashion show, a fixture on the Chicago social calendar since 1927, routinely raises more than $500,000. “The women’s board has long been the largest single donor to the Center,” says Mimi Mitchell, chair of this year’s event. Over the next five years, the board aims to raise $10 million for the new Women’s Board Heart and Vascular Center.

From women’s boards to women’s clubs, North Shore women have been rolling up their sleeves to make the world around them safer, healthier, and more enlightened for more than a century. But what women are accomplishing in philanthropy today goes far beyond traditional structures — beyond what any woman might have imagined possible 50 or 100 years ago. For the first time in Chicago and North Shore history, women like Nancy Searle and Alexandra Nichols are assuming roles once reserved for their male counterparts.

Searle, a Winnetkan married to the great-great-grandson of pharmaceutical manufacturer G.D. Searle, describes herself as “privileged to be in a position to make significant change — to support systemic efforts that make a great place better.” She focuses much attention on education in Chicago. Over a light breakfast at Café Buon Giorno in Winnetka, before her daily swim, Searle describes her philanthropic schedule. “I’m particularly proud of my work with New Schools for Chicago,” she says, “because it has the potential for strategic impact on all Chicago schools.”

She sits on boards of various education programs and cultural institutions throughout the city, but perhaps her greatest impact comes from her work with the Searle Funds at the Chicago Community Trust, which champions biomedical research and education through a collaboration between the University of Chicago, Northwestern, and the University of Illinois at Chicago.

It’s those who chair capital campaigns, however, who often shoulder the heaviest philanthropic loads — not because their work is more important, but because they lead very public efforts to raise what usually amount to extraordinarily ambitious sums intended to elevate institutions to new levels.

Alexandra Curran Nichols recently proved herself to be one such leader. She discovered the Music Center of the North Shore 24 years ago when she brought her children there for piano lessons. She fell in love with the center’s mission “to bring music into so many lives in so many different ways,” stayed on as a volunteer, and became a trustee 11 years ago. When the center had the chance to purchase and renovate Evanston’s First Church of Christian Science, Nichols and her husband bravely volunteered to chair the capital campaign that ultimately raised $10 million and renamed the center the Music Institute of Chicago.

Anne Heller, who chaired the Lincoln Park Zoo Women’s Board’s “Zoolin Rouge” ball, described her volunteer work as “easily averaging 10 to 15 hours per week — more as the date gets closer.” Nichols calls her own capital campaign efforts “as difficult as climbing straight up a wall for four years — a complex machine with multiple constituencies that all have to work together.”

Why do they do it? “The importance of giving back to Chicago and to its people bubbles up in almost every meeting I attend,” says Smith, who has worked on behalf of nearly every civic institution in the area. Nichols, a Fulbright scholar and Northwestern MBA, agrees: “John and I have never seen the commitment to not-for-profits and giving back that we have here.” She believes that sense of civic responsibility has helped make Chicago “the most beautiful and civilized city in the world.”

Neither New York nor Los Angeles has women’s boards. Smith smiles and says, “The merry wives of Greenwich would never join a women’s board.”

How to Start a Women’s Board

(and stabilize an international cultural institution while you’re at it)

The woman who helped start the Joffrey Ballet’s women’s board, Maureen Dwyer Smith of Lake Forest, honed her organizational and civic skills with over 30 years of hard work and service to Chicago, her adopted and now beloved hometown. She sits on boards supporting the Art Institute of Chicago, Field Museum, Lincoln Park Zoo, Northwestern University, and Rush University Medical Center. That work, she says, has taught her “humor, taste, how to listen, and when to keep my mouth shut.”

Smith’s strategy for building a successful women’s board includes:

- Gain the confidence and cooperation of the board of trustees. The female trustees — and the wives of male trustees — will likely become your first members.

- Call in your friends. Smith credits many with incredible support, including philanthropic luminaries such as Kay Krehbiel, Shirley Ryan, Christina Gidwitz, Bonnie Deutsch, and Renée Crown.

- Give it roots and wings. Start with a small group that loves to give back — a sentiment more common in Chicago than in New York or L.A. — then expand the board to achieve high-flying dreams. The original 60-member board now numbers over 130.

- Make your cause emotionally accessible. The Joffrey creates events that tap into the universal dream of young girls to become prima ballerinas.

- Make no small plans. Next year’s gala, an extravaganza in Millennium Park, promises to bring dance into the hearts of Chicagoans of all ages and backgrounds.

How to Run a Capital Campaign

Chairing a major fundraising campaign can feel like “climbing straight up a wall,” as Alexandra Nichols puts it. Success requires focus, collaboration, and endurance — and a clear sense of purpose that unites multiple constituencies under a single goal. Nichols and her husband led the Music Institute of Chicago’s $10 million capital campaign, transforming a neighborhood music school into a world-class cultural institution.

- Stay focused on the mission. Keep every committee and volunteer aligned on the central goal throughout the campaign.

- Build trust and transparency. Regular communication with donors, staff, and board members ensures momentum and confidence.

- Lead by example. Nichols and her husband personally contributed and chaired the effort — inspiring others to follow suit.

- Celebrate milestones. Recognize progress and success at every stage to sustain enthusiasm through long campaigns.

- Honor Chicago’s culture of giving. As Nichols says, the city’s commitment to philanthropy is “unique to this city” — a legacy worth preserving.

This article was originally published in the September 2005 issue of North Shore Magazine.