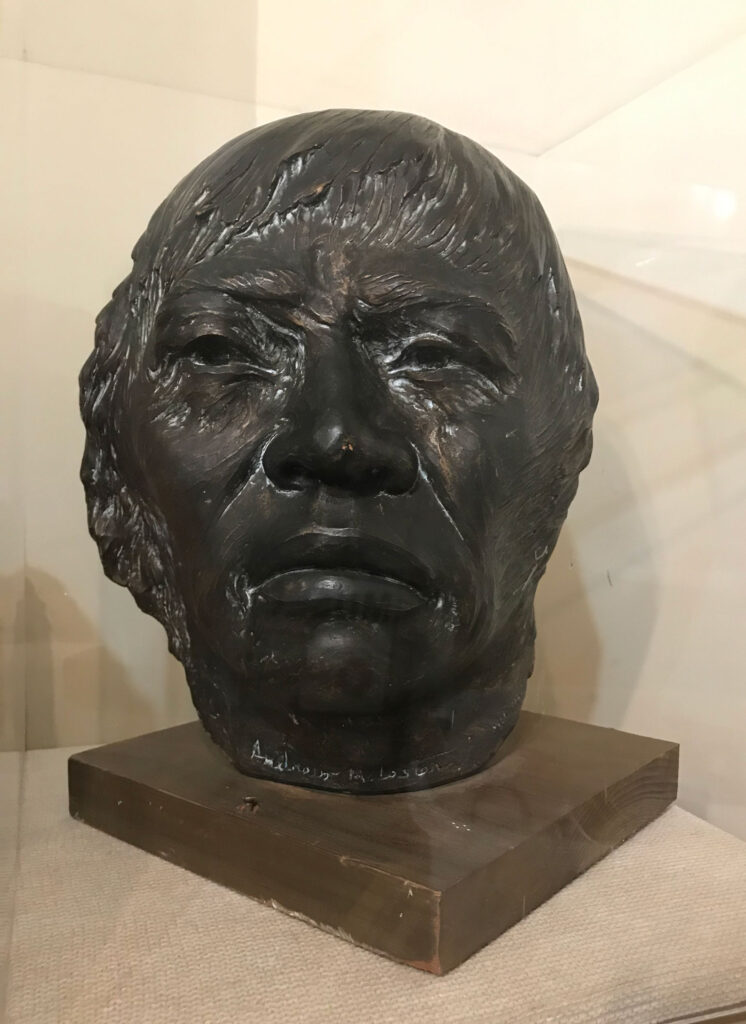

By now most residents of Marin County have heard the name of the legendary Miwok leader “Chief Marin,” for whom the county was named. But Marin was neither his Miwok name, nor the one that the Spanish missionaries gave him. His original name was Huicmuse (pronounced hwik-moose), and the Spanish gave him the name Marino after he was baptized at Mission Dolores in 1801. Far more than merely serving as the county’s namesake, however, Huicmuse made an enduring imprint on Marin County, and the Coast Miwok people of early California, leaving a cultural and physical legacy that can still be felt and seen today.

A Life of Leadership and Resistance

The territory of the Coast Miwok people encompassed Marin and southern Sonoma counties, and Huicmuse’s Huimen tribe occupied what is presently Mill Valley, Tiburon, Belvedere and Sausalito. While Huicmuse’s exact birthplace is uncertain, he was born in 1781 in southern Marin County, according to College of Marin anthropology instructor Betty Goerke, whose 2007 biography, Chief Marin: Leader, Rebel, and Legend, recounts the story of how Huicmuse defied Spanish authority over his people. “He didn’t give up the traditional values of his people even after he lived at Mission San Rafael,” Goerke says.“He was also able to learn and use the new rules of his oppressors to his and his tribes’ benefit.”

Huicmuse’s association with the region’s missions began at age 20, when he moved to Mission Dolores and took the name Marino. Decades later, General Mariano Vallejo named Marin County after the legendary Miwok chief, shortening the spelling. Marino worked at this mission for nearly 15 years, using his skills as a boatman and reader of tides to guide missionaries on various outings on the Bay. He thus had more freedom to come and go from the mission than most Native Americans there, who were locked in their quarters every night.

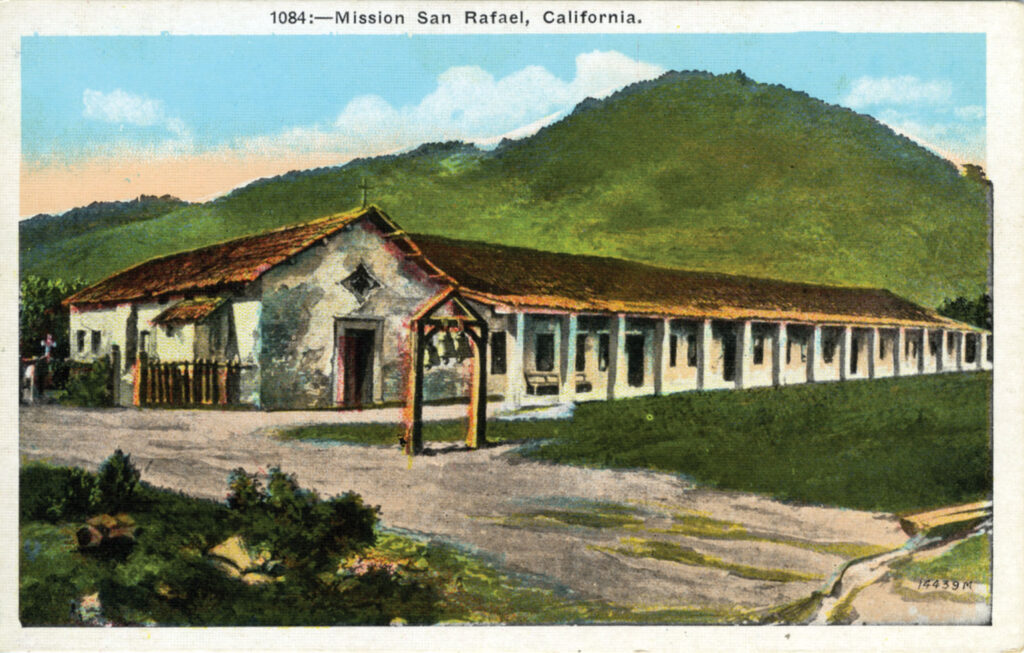

Still, Marino found mission life to be restrictive. In 1815, he ran away and hid out in the Olompali area near present-day Novato, but was captured in 1816 and returned to Mission Dolores. By then, the Native American residents there were dying from European diseases at an alarming rate. So in 1817, a new mission was started in San Rafael, where the priests thought the sunnier climate would be healthier. Marino was relocated to San Rafael, where he lived and worked until 1824. He was made an alcaldle in 1819, which was an Native American overseer with considerable independence. In 1821, Marino accompanied a Spanish expedition to explore the territory north of San Rafael, acting as a guide for soldiers and priests as they trekked through Marin and Sonoma counties to the Chico area and then down along the Sacramento River. After returning to the mission however, he chafed under the strict discipline of the priests.

In 1824, Marino left the mission, hiding from the Spanish on various islands in the bay for the next 18 months. He participated in a raid on Mission San Rafael in 1824 with other Native Americans, including an ally named Quintino, (whose name Vallejo later used for Point San Quentin, again changing the spelling). The priests weren’t harmed in this raid, but some of the buildings were burned. In 1825, Marino was caught and sent to San Francisco’s Presidio, where he was imprisoned for a year. Over the next six years he stayed mostly on the Peninsula, where he worked as a boatman and shipbuilder, and was a godfather to several Native American children baptized at Mission Dolores. In 1832, Marino returned to live at Mission San Rafael, where the following year, he instigated a major reform of the mission system. In April, he sent a complaint to Vallejo about the frequent whippings inflicted on the Native Americans for any infractions of the rules, despite earlier decrees against it. Vallejo wrote to the governor to support Marino’s objections, and in June 1833 whippings were mostly curtailed at the Northern California missions, although these horrific punishments were still meted out for serious infractions.

From 1832 until 1836, Marino held a leadership position at Mission San Rafael, having an authoritative role in political, religious and social affairs among the Native American population there. He also continued to be a godfather or witness to marriages at the mission. In 1834, he conducted a survey of the mission lands with Lieutenant Ignacio Martinez. He ceased participating in mission affairs after 1836, possibly due to illness, and died at Mission San Rafael on March 15, 1839, at the age of about 68. His unmarked grave may still be in the mission’s former cemetery, which was paved over decades ago.

Revisiting Miwok History

The strength and dignity Marino and the Miwok exhibited, despite the abuses they endured at the hands of Spanish and American settlers, is merely one aspect of their culture that inspired Goerke in her research of Marin’s indigenous people. “I respect and admire the culture of the Coast Miwok, because of their respect for the land and their respect for the dead,” she says.

While there are about 850 Miwok sites in the vicinity, many of which have been rediscovered in recent years by archeologists, nearly all of these sites were heavily damaged by souvenir hunters in the late 1880s and early 1900s, or covered over by later developments. There are, however, two places to visit in Marin County to learn about Miwok history and culture.

One is the Museum of the American Indian, which opened in 1967, and is located on the site of a former Miwok village in what is now Miwok Park in Novato. After a construction project unearthed a mass of artifacts there, the Novato High School Archaeology Club conducted a study and excavated the site. They lobbied to have the artifacts saved in a permanent collection, and a two-story house was moved from downtown Novato to the park to house them, along with tribal artifacts from all over the Americas. On the museum’s grounds, there are also recreations of Miwok structures: two homes (or kotchas), one constructed from redwood bark and one of tule reed; and a small granary made of willow branches.

The laws surrounding excavations have changed over the years to respect tribal culture, so collections like those at the Museum of the American Indian have become even more valuable. “There are no longer any archeological excavations of Miwok sites, since that would be desecrating sacred ground,” says museum director Victoria Canby, who identifies as Dine’ (Navajo). For example, when Native American human remains are discovered at a construction site, the work is halted while local experts try to contact living descendants in the area, so that they may claim the remains. If they are unable to reach any, the remains are reinterred into the ground.

There are many people who identify as Miwok still living in the Bay Area (an exact figure is unknown) — a population the museum hopes to better serve in the coming years. “[The museum’s mission is] to improve Native visibility in Marin County going forward, as part of our revised plan to become a cultural center, to provide resources and support to our local indigenous community,” Canby says.

Another place to experience Miwok culture and artifacts in Marin County is Olompali State Historic Park, just north of Novato. The name Olompali means “southern village” in the Miwok language, and Coast Miwok people inhabited parts of this 700-acre park from 6,000 BCE until the early 1850s.

The village that was once here was one of the largest Miwok communities in Marin County. There are two interesting Miwok sites along the park trail: a recreation of a Miwok village and a large grinding rock made of volcanic stone that Miwok villagers used for grinding seeds, greens, berries and nuts before cooking them to eat. Among the historic sites within the park grounds are the remains of the adobe home of Camilo Ynitia, whose father was the last hoipu, or headman, of the Miwok community there and who may also have built an earlier adobe nearby. The walls of the Camilo Ynitia Adobe were encased in a wooden building that was later incorporated into the stucco walls of the Burdell Mansion, constructed after Ynitia sold his land to American settlers in 1852. Built around 1837, the adobe is a California Historical Landmark and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. As the only surviving Spanish-era adobe in Marin County, its remains are an eloquent reminder of the final phase of the Miwok people as the caretakers of the land they occupied for thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans.

For more on Marin:

- How Did the San Geronimo Valley Get Its Name? A Mystery Rooted in the Troubled History of Spanish Missions and the Coast Miwok

- Origins of the Name of Marin County

- The San Rafael Mission Turns 200 This Year

Mark Anthony Wilson is an author and historian who has had five books published on West Coast architecture. He teaches art history at Santa Rosa Junior College.