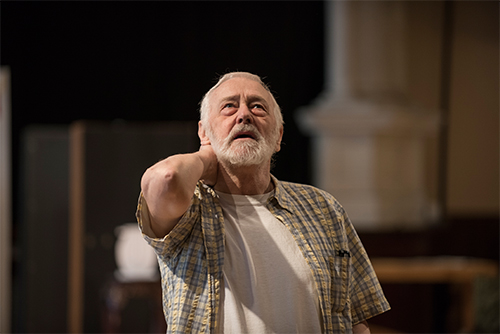

There’s no mistaking that voice. It commands your attention, immediately reminding you of the many famous roles he’s taken on, be it stage, screen or TV. He’s the prototypical American man, Mr. Guy Next Door. In reality, he’s British by birth.

John Mahoney was born in England during World War II, the seventh of eight kids. He followed his sister, a war bride, to the U.S., winning citizenship after a stint in the Army. He settled in Illinois, got his B.A. at Quincy College, and a Masters in English from Western Illinois University, taught college English, and then edited a medical journal. He was 37 before he returned to the stage, his childhood passion, and went right from acting class to professional theater roles.

Mahoney joined the Steppenwolf Ensemble in 1979, and from there, he headed to Broadway, where he won a Tony in 1986 for “The House of Blue Leaves,” and then on to great acclaim in a nine-season stint as Martin Crane on the NBC ‘90s megahit, “Frasier.” Mahoney would tell you that he was in the right place at the right time, but it’s so much more than that, of course. His everyman qualities — the gruff voice and average Joe appearance, combined with his inherent humanity — make him, paradoxically, the center of attention in any production. You root for this man, and it’s no wonder that you do. He might be the nicest man you ever meet in real life.

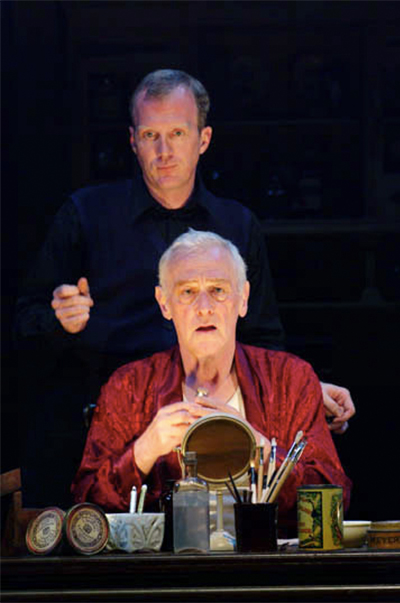

This September, for the first time in two years, he will appear on the Steppenwolf stage in Jessica Dickey’s “The Rembrandt,” directed by Hallie Gordon and co-starring fellow Ensemble member Francis Guinan. It’s a transformative piece about the power of art, something Mahoney can relate to. The following is an edited version of our interview with the acting legend. At 76, he’s still passionately curious about and deeply engaged in the process of making great theater.

Make It Better: What took you from teaching English and editing a medical journal to acting?

John Mahoney: I’d always loved acting as a kid, but when I came to the United States, I didn’t want to be the archetypal scrounging brother-in-law. I didn’t know what to do, but I didn’t want to do something as risky as acting. I got my Masters in English at Western Illinois. I worked through college and grad school at a hospital, so I had six years of a medical background, which took me to a medical journal. It was never anything that I wanted to do, but I was flat-out a bad teacher. So I thought to myself, “I’ve got to try something to satisfy my soul.” I’d done a lot of acting as a kid, been part of the Stratford Children’s Theatre when I was growing up. Everything said, “This is something I want to do. I’ve got to at least try it.” So that’s what I did. I enrolled in an acting school at the old St. Nicholas Theatre, with Bill [William H.] Macy, and I got cast out of the class into David Mamet’s then-latest play — Mamet had helped start St. Nicholas — and everything just fell into place after that. I got a lot of offers, joined Steppenwolf, and everything just worked out from there. It was something that I was meant to do all along, but it took many years for me to finally get the courage to do it.

You joined Steppenwolf in 1979, brought in to the Ensemble by John Malkovich. How did that come about?

At the time, they were moving their theater from Highland Park to the Jane Addams Center in Chicago, and to celebrate the move, each member of the Ensemble was invited to bring somebody in, because they wanted to double the size of the company. I was the one that John brought in, because we had done a play at St. Nicholas together and we just got along very well, so he invited me to become a part. And that was it.

My first production at Steppenwolf, I wasn’t yet a member … it was “Philadelphia, Here I Come” while they were still in Highland Park. John called and asked me to take this part. At that time, though, I was Equity, and they said I couldn’t do the part without being paid, but Steppenwolf couldn’t afford to pay me. So what I agreed to do, gladly, was that Steppenwolf would pay me, and I would sign the check back over to them. The first show I did as a member of the company was “Waiting for Lefty.” It was the first play of the first season in Chicago.

And from there to Broadway…

I did a few plays at Steppenwolf, and finally did this play called “Orphans,” which was a huge hit in Chicago. [They] transferred the entire cast, Kevin Anderson, Terry Kinney and me, with Gary Sinise directing, to New York Off-Broadway and it ran there for a year. It really established all three of us, and of course Gary as a director. I won a couple of awards — Theatre World Award, a Drama Desk nomination — and then came back to Chicago to do “You Can’t Take It With You” at Steppenwolf. Then I was invited back to do “House of Blue Leaves” at Lincoln Center, which transferred to Broadway, and I won a Tony Award for that part. That sort of put me in a different category of not having to audition for anything, having my choice of roles. It really made my career.

You’ve had some wonderful movie roles — the dad in “Say Anything…” was a favorite of mine — but is there one you prefer?

Oh, yeah, me too. That was my favorite movie role of all the ones I ever did. It’s funny … most women like “Moonstruck” best, and most men like “Tin Men” best, and a certain age group likes “Say Anything…” And I agree with them! It really was a great movie.

How about on TV?

I’ve done quite a bit of TV, but the most fun of all, of course, was “Frasier,” because it was such a class act. It was one of the best-written series ever, I think, and we won God knows how many Emmy Awards. It was just such a perfect cast, all of us from very similar [professional theater] backgrounds. I think Kelsey [Grammer] was doing Shakespeare in the Park with Joe Papp when he was cast in “Cheers” and then in “Frasier;” David [Hyde Pierce] was touring the world in a David Brooks’ production of Chekhov, Peri [Gilpin] was from a big theater in Dallas, Texas, and Jane [Leeves] had done a lot of theater in England, so we were all from the idea of putting on a great show, and “Frasier” was just 11 years of bliss, to tell you the truth.

Tell me about the new play that you’ll appear in at Steppenwolf this fall, “The Rembrandt.” What drew you to it?

It’s about our relationship with art, how it enriches our spirit, but doesn’t necessarily reward the artist. I play Homer, and I also play an old, present-day poet dying of cancer. It’s about an exhibit that a young woman goes to see, and gets involved conversationally with some people at the museum, and they all decide to touch the painting, and barely escape with their jobs. But the effect it has on them, this attempt to get closer to the soul of art … it may sound dry, but it’s very, very funny and thought provoking. Best of all, it stars Francis Guinan, the best actor in Chicago, and he plays both Rembrandt and the man guiding the exhibit at the museum, who also happens to be the partner of the man who is dying of cancer, who is played by me. [There is] an amazing scene together toward the end between the two of [us]. It’s about man’s relationship with art, and it’s his yearning, whether he knows it or not, to get closer to it, and to the creation of art itself.

I’ve read that you believe you were simply in the right place at the right time, that you’ve been extraordinarily lucky in your life and your career. But everyone I’ve spoken to sings your praises, not only as an actor, but as a human being.

Thank you for telling me that. It’s very important for me to be liked. That might sound strange to you, but it is. Because if you are liked, then you are treating people well. And that’s what I want most of all. I have a mantra that I say several times a day. I say, “Dear God, please help me to treat everybody — including myself — with love, respect and dignity.” And I figure if I do that, then people are going to like me. And if somebody doesn’t like me, then I figure I’m not being very nice to them. And it’s important to me that I am. Rotten people, I don’t care. But most people are very decent. So it’s important to me to hear what you’re saying. Because it means that I am treating people the way they are supposed to be treated.

I think that humanity comes through in everything that I’ve seen you do.

Thank you. Really.

You’re a cancer survivor. Does it influence or inform your choices on stage?

It’s not my first time. I had cancer over 20 years ago, and my career was doing so well, I just wanted to keep doing as much as I could, as fast as I could … I was trying desperately to make up for all the time I had wasted before I became an actor. This last bout of cancer, it changed me in that it definitely weakened me. I’m over it, according to my doctors, but I am weaker, and there are some plays I can’t do anymore that I could do six or seven years ago.

Beloved Chicago actors of a certain age: a cage match between you and Mike Nussbaum. Discuss.

(Laughs ) I love Mike. Working with him is absolutely wonderful. And you don’t know the half of it. He does books of double crostics every day in ink. I do them too, but not in ink, and nowhere near as fast. There’s no BS about Mike. It’s so joyful to be on stage with him, to watch him work, to listen to him dissect a part, and see where he’s coming from, how he works. And funny! I’m thrilled for these latest reviews (as Einstein in “Relativity” at Northlight Theatre in Skokie) and I can’t wait to see him in it. I’ve got a bit of chemo brain now. It’s not as easy to remember lines. My mind is still pretty sharp, but I couldn’t do what Mike does, and I’m only 76. I hope he keeps on doing it.

More from Make It Better:

- Best of 2017: Arts & Entertainment

- 7 Great Chicago Theater Companies Where You Should Consider Subscribing

- The Yard at Chicago Shakespeare: The Groundbreaking New Theater You Won’t Want to Miss

Julie Chernoff, Make It Better’s dining editor since its inception in 2007, graduated from Yale University with a degree in English — which she speaks fluently — and added a professional chef’s degree from the California Culinary Academy. She has worked for Boz Scaggs, Rick Bayless and Wolfgang Puck (not all at the same time); and sits on the boards of Les Dames d’Escoffier International and Northlight Theatre. She and husband Josh are empty nesters since adult kids Adam and Leah have flown the coop. Rosie the Cockapoo relishes the extra attention.