From Chile’s Atacama Desert to Japan’s floating solar farms and Texas wind corridors, photographer Jamey Stillings uses his Fujifilm GFX100 to capture the sweeping transformation of the world’s energy landscape.

Through his multi-decade project, Changing Perspectives: Renewable Energy and the Shifting Human Landscape, Stillings shows how photography can be both a source of information and a catalyst for change — reminding viewers that building a carbon-constrained future is crucial to life on Earth and, he hopes, motivating action toward it. While the world marks Sun Day on September 21 to celebrate renewable energy, Stillings’ work underscores that this shift is not a single day’s cause, but an ongoing effort carried out year after year across the globe.

Under the umbrella of this project is Stillings’ latest book, ATACAMA, in which he shares his distinctive aerial perspective to examine large-scale renewable energy projects and the visual dynamic of land-scarring mining operations and the beauty of the Atacama Desert. Chile produces a third of the world’s copper and has one of the largest known lithium reserves. These resources are used daily in cars, computers, and smartphones. The country’s mining industry has traditionally been dependent on imported coal, diesel, and natural gas for its energy.

There are positive signs not only on the horizon but also currently operational. The Atacama Desert’s new renewable energy projects, including solar and wind, are now supplying significant electricity to the northern grid, transmitting power to population centers in the south, and thereby reducing mining’s dependence on fossil fuels. Stillings’ images of these state-of-the-art energy projects might help viewers to rethink and reposition how we refer to them.

As environmentalist Bill McKibben writes in his book, Here Comes the Sun: A Last Chance for the Climate and a Fresh Chance for Civilization, “We still think of photovoltaic panels and wind turbines as ‘alternative energy,’ as if they were the Whole Foods of power, nice but pricey. In fact, and more so with each passing month, they are the Costco of energy, inexpensive and available in bulk.”

In the images and reflections that follow, Stillings guides us across the solar fields, wind corridors, and mining sites where our energy future is taking shape.

Pampa Elvira Solar Thermal Plant — Atacama Desert, Chile (2017)

“The Atacama project shows a nexus of renewable energy and mining,” says Stillings. “And that nexus started to form around 2016, 2017, when the price of creating renewable energy dropped below that of fossil fuel.”

“In Chile, fossil fuel was typically imported to power the mining industry, and all of a sudden, you started to see this shift. Most copper mines in the country are now using 100 percent renewable energy for their electricity. They’re using that at the same time that they’re being asked to mine more copper. Chile is the largest exporter of copper in the world and the second largest exporter of lithium, making its extraction and environmental practices relevant to us all. So, the call to action for my upcoming exhibition in Houston in 2026 is to show people two things: where copper and lithium come from, and how they’re used in daily life. Every time you unlock your smartphone, drive your car, or flip on a light, you tap into the remote landscapes of the Atacama Desert.

This is one of the only solar thermal plants at a copper mine. It is not generating electricity; instead, it creates hot water for the electrowinning process, which involves plating out copper at the end of the refining process into large copper plates. It takes the place of the two diesel generators that were making the hot water.”

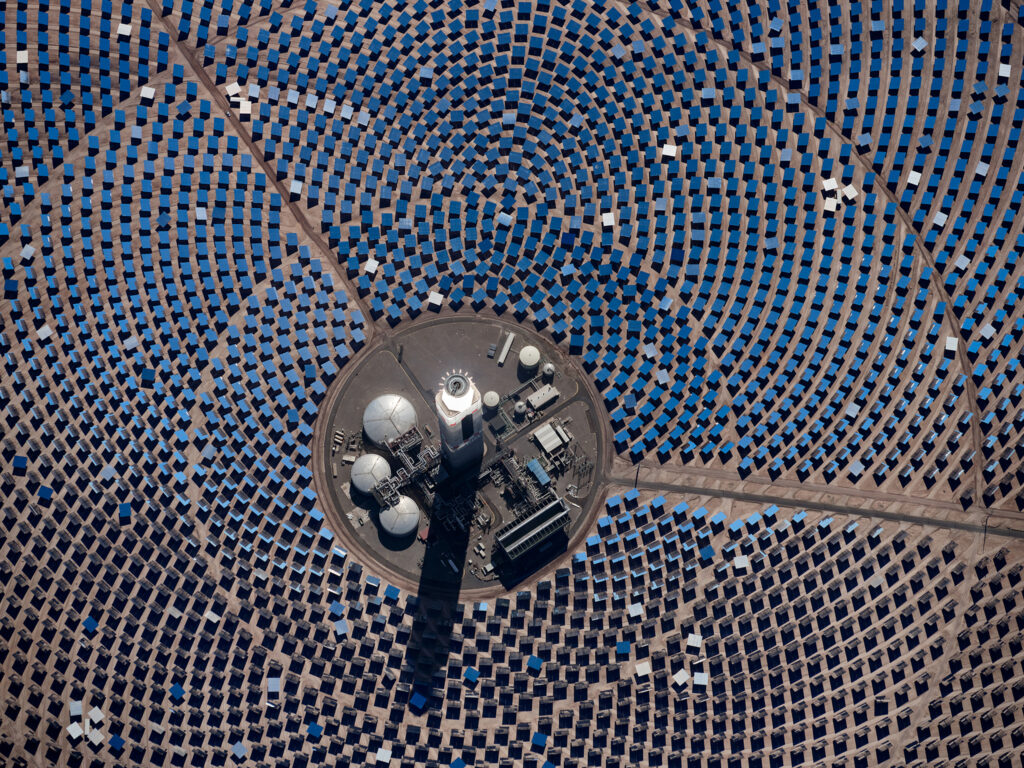

Cerro Dominador Concentrated Solar Power Plant — Atacama Desert, Chile (2022)

“A concentrated solar project is collecting the thermal energy of the sun to superheat either molten salt or water. A photovoltaic project involves solar panels that directly convert sunlight into electricity. The cost of photovoltaic and wind has dropped so much in the last decade and a half that it doesn’t matter what the United States is doing right now. All around the world, more photovoltaic and wind projects are being built than any other kind of energy form.

Battery storage, along with various other forms of storage, is a key component because the goal with renewable energy is to align electricity demand with energy production. With a solar project, when the sun’s up and you’re generating electricity, you have to deliver it to the grid. And when it’s windy and wind turbines are turning, you’ve got to deliver that to the grid. But what happens if the demand is higher or lower at that point in time? Do you turn electricity production off? No, of course, you create some storage to collect the energy to deliver the electricity when everyone comes home and turns on their air conditioning.

For example, they superheat molten salt and store it in a tank. When the sun goes down, you can use that thermal energy to heat water and drive a steam turbine, allowing you to generate power after sunset.

Concentrated solar plants with molten salt are located in Chile, Morocco, Dubai, South Africa, and China. Concentrated solar that only makes power during the daytime does not make economic or technological sense, given what photovoltaic can do for a lot less money during the same time.”

Ivanpah Solar Site Before Construction — Mojave Desert, California (2010)

“Rolling off of my Hoover Dam project, I asked myself, ‘How do I combine my environmental concerns with my interest in the intersection of nature and human activity?’

I went out to the Mojave Desert in 2010 to explore renewable energy projects. As it turned out, the Ivanpah Solar project was scheduled to be the world’s largest concentrated solar power plant upon completion. This photo is when I had three minutes of dappled sunlight over the 14-square-kilometer site before construction began.”

Ivanpah Solar Concentrating Solar Plant — Mojave Desert, California (2014)

“When the Ivanpah project was conceived, the costs of photovoltaic and wind energy were very high, as was concentrated solar. But by the time it was completed a few years later, the price of photovoltaic and wind had dropped sharply, and fracking had entered common usage, which drastically changed the energy economy in the United States.

The cost of purchasing electricity from new wind and solar farms became so much lower per megawatt-hour than from a concentrated solar plant. As a result, the Ivanpah project ended up being an expensive way to produce electricity, so it is likely that the whole project will be decommissioned early.

I aim to document its decommissioning process to examine the life cycle of a power plant and understand what happens to its resources. I want to document whether the land gets repurposed, possibly as a photovoltaic power plant, or if it is returned to its “natural” pre-construction state.

Ivanpah has been a punching bag, but I look at it this way: ‘If the first time we sent a rocket up and it exploded,’ would we say, ‘Okay, that just proves we shouldn’t be putting rockets up in the air?’ We’re going to make mistakes along the way. None of this is perfect. Every single project, whether it’s a renewable energy project or something else, has compromises involved and adjustments that need to be made.”

Floating Photovoltaic Project — Hyogo Prefecture, Japan (2016)

“I especially love the floating photovoltaic projects in Japan. This pond has photovoltaic panels that directly capture sunlight and convert it into electricity. Placing them on a pond offers several benefits. It’s more efficient because of the evaporative cooling from the water, it’s quite resistant to earthquakes, and it doesn’t compete with land used for recreation, urban development, or agriculture.”

New Wind Transmission Lines — Near Haskell, Texas (2021)

“These transmission lines are moving wind energy into the grid. Right now, President Trump is essentially trying to kill wind and solar and bring back coal, natural gas, and oil. While he can slow that down in the United States, it’s not changing what’s going on in the rest of the world; they’re marching forward.

You have huge amounts of solar energy that’s being created in Morocco, Dubai, and other countries in the Middle East. China generates more renewable energy capacity annually than the rest of the world combined. The rest of the world’s going to adopt electric cars for economic and environmental issues.”

Mina Chuquicamata Copper Mine — Atacama Desert, Chile (2017)

“Chuquicamata copper mine, located north of Calama in the Atacama Desert, is one of the largest mining pits in the world. It’s five kilometers from the north to the south end of the pit. They are now mining this deposit underground.

Many countries around the world are still heavily dependent on coal. It is an inexpensive and accessible source of energy, but it’s the dirtiest source of energy. In the case of our country, we’re wrestling with climate denial and the harmful effects of fossil fuels, in particular coal. Climate change will happen whether we believe it or not.

Fracking has enabled the extraction of much more natural gas from underground, greatly increasing supply and causing prices to drop. As a result, there’s now a large amount of natural gas that can compete with lower prices for renewable energy.

It’s still not as cheap as solar and wind, but many see it as a good bridge between coal and other sustainable, long-term energy sources. However, fracking uses millions of gallons of water, which becomes completely unusable afterward. It depletes aquifers, and there is a risk of polluting them along the way.”

Valle de los Vientos Wind Project — Atacama Desert, Chile (2022)

“When you wake up in the morning in the Atacama, the wind howls from east to west. The air descends from the Andes and moves toward the coast, and these turbines face the mountains. Around midday, the wind shifts. By mid-afternoon, it roars from the west coast toward the east.

The mornings and evenings are high-wind periods, with a lull in the middle of the day and often at night. So, you’re taking advantage of that. If you have solar projects nearby, they’re generating electricity during sunlight hours. That means they produce less when the sun is low and more when the sun is high, and they stop when the sun sets.

If you look at a geothermal plant, you might say, ‘We’re going to really amp up the creation of electricity from that geothermal plant to fill in the gaps when the wind or solar are down. We’re going to use that as a stabilizer in our power flow.”

Desert Sunlight Photovoltaic Power Plant — Desert Center, California (2015)

“Desert Sunlight was, for a while, the largest photovoltaic power plant in the world. A decade ago, companies were competing to make the “largest project” as a status symbol of progress.”

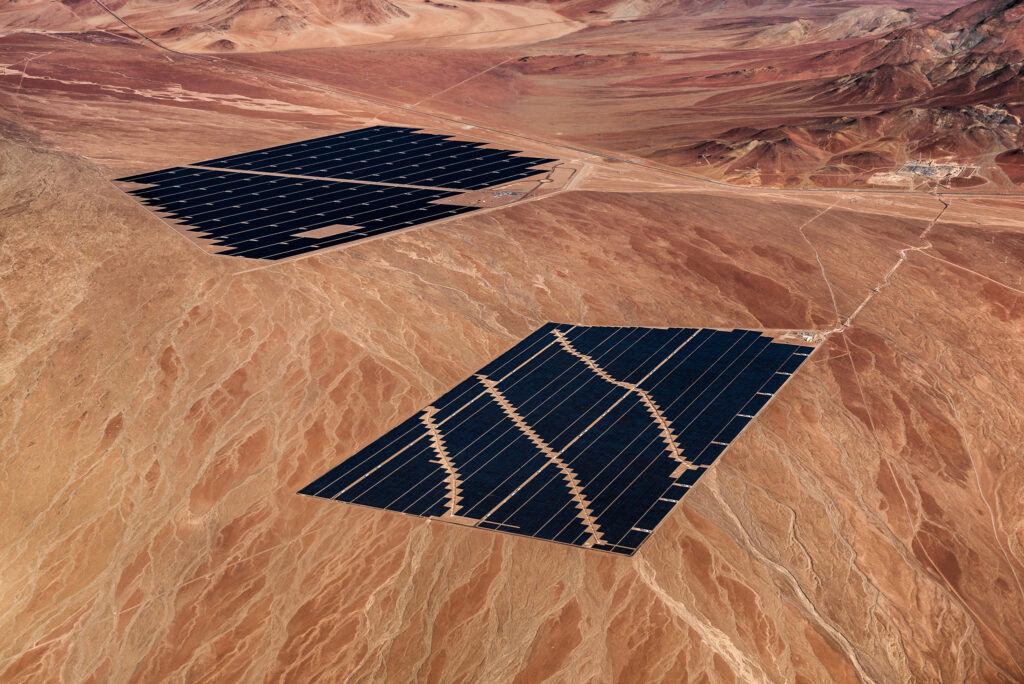

Carrera Pinto I and Luz de Norte Photovoltaic Plants — Atacama Desert, Chile (2017)

“What we’re doing as human beings will change the planet. Whether we choose to do things that mitigate the negatives in that path, that’s a decision we have to make. But we have a hard time saying, ‘What’s it going to be like for two or three or five or seven generations out? How will our actions impact those people?’ For the most part, as a species, we lack the bandwidth and intellectual capacity to act based on that kind of perspective. We act based on what’s good for us right now.

From the onset of my Changing Perspectives project back in 2010, I’ve been more interested in documenting our attempts to find solutions than I am in trying to document the problems. They say that 90 percent of imagery is focused on the problems and only 10 percent on solutions.”

Behind the Lens: Jamey Stillings at Work

“My undergraduate work was in art and art history, and I received my MFA in Photography at RIT in 1982. I worked in the commercial world to support my personal projects, often documentary photography to promote social change.

I’m now 70 and was diagnosed with prostate cancer over two years ago. I’m in remission, but when you have a bout with cancer, you kind of switch gears. I want to optimize my creative path, my personal work, so I’m circling back to a greater emphasis on personal projects. I’m dedicated to exploring the intersection of art, the environment, and our evolving relationship with the planet.”

How to Help

The Make It Better Foundation is a proud supporter of Jamey Stillings’ exhibition, ATACAMA: Renewable Energy and Mining in the High Desert of Chile, at the Houston Museum of Natural Science during the 2026 edition of FOTOFEST, and his multi-decade Changing Perspectives project. Join us in supporting his enlightening work by donating.

You can join Jamey Stillings in supporting his favorite organizations, such as Social Documentary Network, National Resource Defense Council, Environmental Defense Fund, 350.org, and Sierra Club.

Award-winning Director of Photography Mark Edward Harris

Mark supports:

Center for Great Apes

Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation

Search Dog Foundation

His books include:

Faces of the Twentieth Century: Master Photographers and Their Work

The Way of the Japanese Bath

Wanderlust

North Korea

South Korea

Inside Iran

The Travel Photo Essay: Describing A Journey Through Images

The People of the Forest