Four years after the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, news cycles continue to serve up potentially traumatic events that remind us resilience is fundamental to successfully navigating crises. At the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence, we recently unpacked research conducted during the pandemic to gain a better understanding of how people were feeling. What we learned might surprise you.

We analyzed more than 3.5 million responses from the more than 150,000 people who used the How We Feel app from May 2020 to February 2021 and reached several conclusions.

Happiness during a pandemic?

Popular perception would lead us to believe that people in our study would report feeling worse over time as the pandemic weeks grew into long months. However, the data reveal the opposite: people reported experiencing more positive emotions as the pandemic continued.

Other studies have revealed that almost half of Americans reported symptoms of anxiety or depression in 2021, but the increase in reported diagnosable conditions is not the whole story. Our study uncovered people’s day-to-day emotional lives during the pandemic and revealed emotional well-being and resilience trends characterized by more pleasant than unpleasant feelings.

Creating an app to measure emotions

Building on the foundation of an app designed to collect individuals’ COVID-19 physical symptoms, the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence created a survey that asked people to describe their feelings to understand their everyday emotional experiences better.

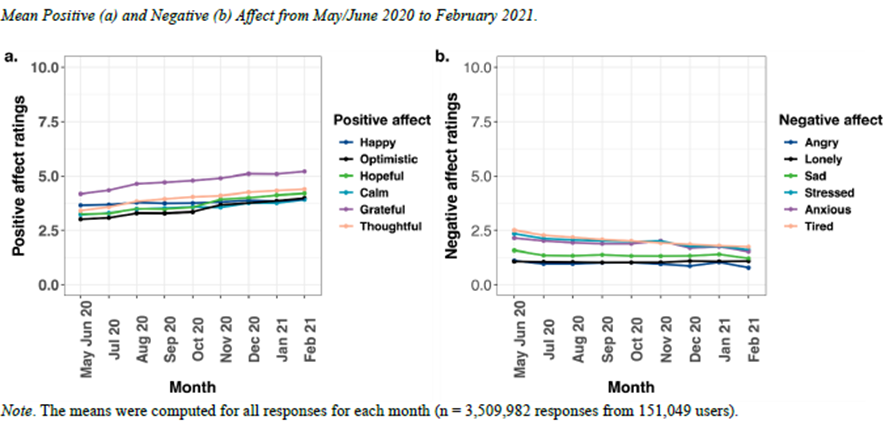

We looked at the personal experiences and data from 151,049 app users who elected to participate in this form of participatory citizen science. Every day, they were asked how strongly they were experiencing six pleasant feelings—happy, optimistic, hopeful, calm, grateful, and thoughtful—as well as six unpleasant feelings—angry, lonely, sad, stressed, anxious, and tired. We gathered and analyzed 3,509,982 discrete feelings reported throughout the pandemic.

From May 2020 to February 2021, when we first began tracking data, people reported experiencing more pleasant (happy, optimistic, hopeful, calm, grateful, and thoughtful) than unpleasant (angry, lonely, sad, stressed, anxious, and tired) feelings on a daily basis. But as time passed, reports of pleasant feelings increased, and unpleasant feelings decreased.

Why understanding emotions in crises matters

A seeming paradox, two realities were true at the same time: anxiety and depression conditions spiked globally while day-to-day reporting of emotions showed an increase of pleasant feelings when individuals checked in with their emotions at a given moment. This is not unlike other historical reports of wartime or national crises, where people directly experiencing war remember the fear and the grief but also the courage, camaraderie, and gratitude for others.

We also discovered key differences in how different groups reported their daily emotions. In particular, young adults and women were the most prone to unpleasant feelings. Compared to men, women were more likely to report feeling sad, stressed, anxious, and tired but less likely to report being angry. For all the complaints of being cooped up with one’s family, people living alone reported feeling more sad and had fewer pleasant feelings than those living with others. Exposure to stressful circumstances such as illness, lack of sleep, or COVID-19 was also related to reduced pleasant feelings.

Despite their disproportionate risk of COVID-19 infection in the early days of the pandemic, African American and Hispanic users also reported more pleasant than unpleasant feelings. Our study found no difference in reports of unpleasant feelings among healthcare workers, other essential workers, and non-essential workers. Despite the risks, healthcare workers reported more pleasant feelings than non-essential workers, perhaps due to a bolstered sense of meaning and purpose.

Studies show that pleasant emotions generally benefit our psychological and physical health. However, our research identified an overlooked downside of feeling happy. Happiness gives us a sense that our circumstances are good, which can lead to us being less cautious. Our data showed that people who reported feeling happy left home more frequently and were not as diligent in following social distancing guidelines. They took more risks, perceiving preventive behaviors as less necessary. Whereas, those who reported more unpleasant feelings acted more cautiously, such as wearing facial coverings. Unpleasant feelings warn us about dangers in our environment and can prompt action that helps us and others.

Key takeaways: resilience vs. risk

After looking at all of this data, we came up with three key takeaways from how COVID-19 impacted people’s emotions and behaviors:

- The results show that people are more resilient than they realize. Indeed, resilience is a rule rather than an exception. George Bonanno, Professor of Psychology at Teachers College, Columbia University, who has been studying resilience for three decades, repeatedly found that it is the most common trajectory for people following trauma and challenging times.

- Our study challenges the popular belief that the pandemic was characterized by only unpleasant feelings. Even early on, when masking and social distancing were required in most places, and no effective treatment or vaccine was available, people reported feeling more pleasant than unpleasant over a day. People found and created moments of joy and calm, hope and optimism, even amidst global crises and personal instability.

- Feeling pleasant, while a goal often striven for, sometimes leads to beliefs that risky behavior is acceptable. Feeling unpleasant, while something often avoided, can actually be self-protective and serve the greater good by prompting individuals to be more cautious for the sake of others.

This research does not discount the very real rise in mental health problems during the pandemic or the importance of treating them. It simply reveals that there is more than one side to the story of human emotion during crises. Such insights add important texture as we continue to process the mental health fallout from the pandemic and prepare for future crises.

How To Help

The Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence (YCEI) is a community and school-based program within the Yale School of Medicine. Its mission is to conduct research and offer training that supports people of all ages in developing emotional intelligence skills. The YECI relies entirely on financial support from grants, training revenue, and philanthropy.

Visit the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence website to learn more about this organization and ways to donate to their essential work.

This post was submitted as part of our “You Said It” program.” Your voice, ideas and engagement are important to help us accomplish our mission. We encourage you to share your ideas and efforts to make the world a better place by submitting a “You Said It.”

More From Better

- Joel McHale to Host GO Campaign’s Star-Studded Vintage Hollywood Food and Wine Fundraiser Supporting Local Heroes

- From Blockbuster Movies to Lollapalooza: How Chicago Philharmonic Is Breaking Genre Barriers and Changing the Game for Orchestras

- Pride Month 2024: How to Support and Celebrate the LGBTQIA+ Community in Chicago and Beyond

Dr. Robin Stern is the co-founder and associate director of the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence, a psychoanalyst in private practice, author of “The Gaslight Effect Recovery Guide,” and host of “The Gaslight Effect Podcast.”