Ami Vitale has spent her career on the front lines of our planet’s most urgent crises, using her camera not only to witness the world but to change it. A National Geographic photographer, writer, documentary filmmaker, and Nikon Ambassador, Vitale began her career covering conflict zones — places where human suffering was raw and unrelenting. But the deeper she looked, the more she realized that many of these conflicts shared a common root: the unraveling of our relationship with nature.

That realization transformed her work. For the past 16 years, Vitale has turned her lens toward the people and communities living on the front lines of war, climate change, and extinction, who refuse to let cataclysm define their future. She highlights stories of resilience and innovation, emphasizing the delicate balance between humanity and wildlife and the urgent need for conservation.

Vitale’s image of Sudan, the last male northern white rhino, in his final moments — surrounded by the people who fought to save him — became one of National Geographic’s most iconic photos of the 21st century. It helped raise millions for conservation and awakened global audiences to what extinction really looks like. Her work documenting pandas in China, too, began not as an assignment but as a story she chased herself—pitching National Geographic with a fresh perspective on a species the world thought it already understood.

Her efforts have not gone unnoticed. She is a Royal Photographic Society Honorary Fellow, has been named Magazine Photographer of the Year at the International Photographer of the Year awards, is a six-time recipient of the World Press Photo awards, and has received the Lucie Humanitarian Award, the Missouri Honor Media for Distinguished Service, and the Daniel Pearl Award for Outstanding Reporting.

But perhaps her most enduring impact lies in her efforts to empower others — especially the next generation. Vitale is the founder and executive director of Vital Impacts, a non-profit organization that uses the power of art and storytelling to support community-based conservation efforts and mentor and elevate emerging photographers who share solutions-based environmental narratives, recognizing the critical role these visual journalists play in spotlighting the efforts of communities to protect our environment and wildlife. And right now you can help support their important work. The Make It Better Foundation is matching all donations to Vital Impacts, up to $5,000, doubling your impact in the fight to support grassroots organizations working to protect endangered habitats and the storytellers who amplify these critical stories

I spoke with Ami Vitale about the moments that changed the course of her career and how she’s using photography to confront extinction, elevate local communities, and inspire the next generation of environmental storytellers.

Mark Edward Harris: I don’t know anybody who uses the camera as a conservation tool more effectively than you. How did this use of photography evolve?

Ami Vitale: My career began reporting on global conflicts, which left me emotionally drained. I began to question whether hope still existed. It was then that I started to make the connection between conflict and the breakdown of nature. Behind virtually every human conflict, you’ll find an erosion of the bond between humans and the natural world around them.

In some cases, it’s the scarcity of basic resources like water. In others, it’s the changing climate and loss of fertile lands. But it’s often the demands placed on our ecosystem that drive conflict and human suffering.

This was the beginning of a journey that began approximately 16 years ago, during which I came to understand the interconnectedness of all life on our planet. Humans play a crucial role in every narrative, particularly those concerning conservation and the environment, as we both impact the planet and represent our greatest hope for its preservation. I began doing research and trying to find the stories that illustrated not just the challenges we face but also the solutions.

MEH: Such as?

AV: On the front lines of almost every story, whether it’s climate change, habitat loss, water issues, or species extinction, there are amazing people who are using creativity and working to find innovative solutions. I wanted to get beyond the dystopian narratives and, instead, urge people to reimagine their relationships with nature.

I began researching rhino poaching and the plight of wildlife. While these stories had received significant attention, the critical role and strengthening of Indigenous communities at the forefront of these poaching conflicts often went unnoticed. These communities living alongside wildlife are essential to protecting Africa’s great animals, yet their voices were being left out of the conservation conversations.

MEH: How did that incredible story evolve?

AV: It happened on a cold, snowy day in a zoo in the Czech Republic when I met a rhino named Sudan for the first time. Quite unexpectedly, this gentle, hulking creature changed the way I saw the world forever. What surprised me was the deep sense of wonder I felt in the presence of this ancient species. Rhinos have been roaming the planet for millions of years, and up until the last hundred years, there have possibly been tens of thousands of them inhabiting the planet. On this day, only eight of these northern white rhinos were known to be alive, and they were all in zoos. I was there because there was a plan to airlift four of these last eight northern white rhinos to Kenya. At first, I thought it was a story straight out of Disney, but I quickly realized that this was a desperate, last-ditch effort to save an entire species from extinction.

When I started that story, I realized that the emphasis was always focused on fighting a poaching war. “We have to militarize!” First, it was men with guns. And then it was, “Oh, look, we’re training women warriors.” The focus was always on human brutality and violence. I rarely heard Indigenous peoples’ voices and how they have always lived with wildlife and can be their best protectors.

Everywhere I go, I see people, often with very little, making huge impacts in their communities and for the planet. I think it’s just as important to shed some light on these stories, where, against all odds, individuals are making a difference.

Flash forward to today. I need to make sure that we are inspiring the next generation of environmental storytellers. I know that solution-based storytelling can create a groundswell of public support and action, driving positive change and helping address the nature crisis effectively. Nick Brandt said this to me, and I love this line, “Somewhere out there, there could be a young photographic equivalent of Greta Thunberg, someone who captures people’s imaginations on a global scale.”

MEH: That’s where Vital Impacts comes in.

AV: Yes, that is why I created our nonprofit, Vital Impacts, to help get more of these stories into the world and to mentor and support the next generation of environmental storytellers.

Stories that showcase successful solutions give people hope. In the face of environmental challenges, hope can inspire action. When individuals see that positive change is possible, they are more likely to engage in efforts to address the crisis.

I started it as an organization simply to raise money to support the conservation on the ground that I saw was working and just needed a little financial help and their stories to be told. Then I realized that wasn’t enough. We need to make sure we are supporting the people who are passionate about environmental journalism, creating opportunities for them, and getting their work into the world.

MEH: Let’s talk about some of the organizations that Vital Impacts supports.

AV: We have rigorous criteria and processes in identifying non-profits that align closely with our mission to support communities dedicated to protecting people, nature, and wildlife. Reteti Elephant Sanctuary is one of the nonprofits we support. It is the first indigenous-owned and run elephant sanctuary in all of Africa. I met the community before Reteti existed. In 2013, Reteti was only a dream, but they succeeded, and the sanctuary opened in 2016.

The first years of the sanctuary were very challenging. No one knew the sanctuary existed, and funding was hard to come by. I did everything I could to use my platforms and media connections to get their story out. I created campaigns to make sure the world knew about Reteti. One of those campaigns was with Dave Matthews, who I met at Standing Rock in North Dakota. I still cannot believe he agreed to bring his family to Kenya with me. We made a film with Dave, created a fundraiser that raised about $800k, and brought a traveling exhibition of my work about the sanctuary on the Dave Matthews Band 2018 summer tour.

This experience marked one of the first times I truly understood the power of photography and journalism. It also taught me the importance of allowing stories to evolve and staying connected with the communities we work alongside.

I had the privilege of being present when the first elephant arrived. I recently returned to document the release of 13 of these elephants back into the wild after their years of rehabilitation.

MEH: The camera and the guitar can be powerful tools in conservation.

AV: Yes!! Our job is to spotlight critical issues affecting our world and to inspire people to become engaged. When I began my career, it was all about being competitive, and people were not supportive of each other. But now, as the media is struggling. We realize we’re better together. I love that. There’s been a total cultural shift. We are all creative souls, and if we work together, we create more opportunities for all of us, and that has always been my modus operandi. That’s why I created Vital Impacts.

MEH: And it continues to grow and expand.

AV: Yes! We have many programs that merge art, journalism, and advocacy. I began Vital Impacts with print sales of iconic photographs from legendary photographers. But then I realized we should include people who may not be well known but have shown a deep commitment to the natural world. Sixty percent of the proceeds are donated to a grassroots nonprofit that is protecting wildlife or nature, while 40 percent goes directly to the photographers to sustain their essential storytelling work.

Environmental storytelling, conservation, and climate action have never been more critical. Every campaign is different. We recently did a campaign for Jane Goodall. When she turned 90, I thought, “Why don’t we celebrate 90 women photographers to honor each year of her life and show the profound impact she had on the world?” It was a wonderful success and a beautiful way to collaborate for a meaningful cause.

Within the first year of Vital Impacts, I realized we could do so much more than just print sales. I wanted to figure out how to support these storytellers and photographers who are just starting their careers in a difficult time for journalism. I created grants and a mentoring program. In the first year, we gave two $20,000 grants, and then in the second year, we gave out $50,000 in grants. Each grant is named for legendary and passionate conservation heroes, including E.O. Wilson, Jane Goodall, Sylvia Earle, Madonna Thunder Hawk, Chico Mendes, Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim, and Ian Lemaiyan. Now, we have seven grants supporting people around the world.

We’ve had people show up to our mentoring sessions by candlelight because there’s no electricity where they live. The world is not equal, so we’re trying to balance that.

We also have a live speaker series for 5th to 9th graders because that’s the most impressionable age range. Most of the speakers are photographers, but we also have Sylvia Earle as a speaker and Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim, an amazing indigenous rights activist from Chad.

We leave behind a resource guide for the teachers to use to teach after we’ve left. We’ve reached more than 20,000 kids all over the United States in just over a year. My greatest wish is to give children the ability to dream and empower them to pursue careers in the arts or sciences. I want them to care about this beautiful world.

MEH: And this all started with your encounter with rhinos.

AV: Yes. There was great hope that the northern white rhinos would breed after they were sent to Kenya, but that never happened. One male, Suni, died in 2014, and then Sudan, the last male, died in 2018 at age 45. He lived a long life and had become a celebrity. Tinder even created a profile, calling him the most eligible bachelor alive. It was a heartbreaking moment when he passed away, and it made the species functionally extinct. There are now only two northern white rhinos left in the world: Najin, a female, who was born in captivity in 1989, and Fatu, also a female, who was born in captivity in 2000.

MEH: So, was that the end of the line for the northern white rhino because there were no more males?

AV: That’s where the story has a beautiful twist. At a moment when it seems like there is no hope, this small group of individuals are banding together, doing everything they can to save this species. It is often in the face of our greatest challenges that human ingenuity and creativity light a path forward. The BioRescue consortium has created 35 pure northern white rhino embryos using the oocytes from Fatu and the frozen sperm from deceased northern white rhinos. They are cryopreserved in a lab in Italy and Germany, ready for future transfers to surrogate mothers. The team is also racing to create lab-grown egg and sperm cells, which have generated primordial germ cells.

MEH: So IVF can save them from extinction.

AV: Last year, they implanted a southern white rhino embryo into a surrogate. The transfer was successful. Curra, a southern white rhino, was pregnant, carrying a viable 70-day-old male embryo in her womb. This tiny creature confirmed the creation of the world’s first successful IVF rhino pregnancy. Still, after heavy rains, the sudden rainfall and flooding unearthed Clostridia bacteria spores, infecting and killing her. It was heartbreaking for all of us. But still hopeful. It confirmed IVF is possible. Now, the ultimate challenge — and hope — lies in implanting the northern white rhino embryo into a surrogate southern white rhino.

MEH: How did your work with pandas come about?

AV: A few years after I started working with the northern white rhinos, I was invited to be a part of a film to document the release of a captive-born panda into the wild. I dressed up as a tree as she was leaving home forever, and afterward, the head of the panda program thanked me for thinking about the panda and offered to let me hold 2 baby pandas! He quickly followed up the offer with, “I only let your President hold one baby panda.” I immediately pitched a story to National Geographic Magazine. It’s not easy to get access to this story, but the editors politely let me know that they had already published a panda story eight years earlier.

MEH: They did sign off on it eventually.

AV: That’s when I got to work. I read everything that had been written about pandas and rewrote my proposal to show how unique the story would be. National Geographic accepted, and I began a magical, three-year journey into the world of pandas.

I want to add that most of my work is not from assignments. I usually pitch all my stories and find interesting angles to make them unique. I like to take stories that people think they understand and surprise them. It’s no longer about traveling to the most remote corners of the earth. Today, the secret is in how you tell a story.

MEH: It’s amazing to hear this from you. It’s great for people to know that just because they’ve built a great portfolio, not everybody’s going to be knocking on their door.

AV: I’ve always been a freelancer. You’ve got to be scrappy and persistent. You must also get used to rejection and not let it stop you.

It takes years of relationships to build trust and to find unique stories.

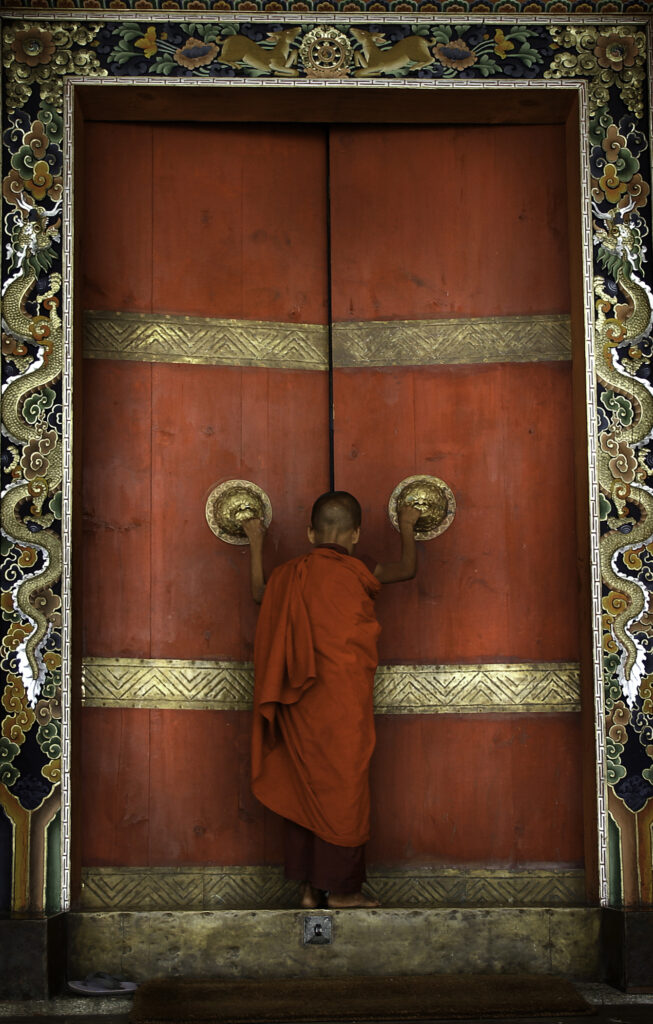

MEH: Gordon Parks told me the same thing many years ago. He was dealing with race as an additional issue. Too many people knock on the door, and if it doesn’t open, they just get back in their car and leave instead of going around to the back door and trying another entry.

AV: What a great metaphor! It’s also easy to get caught up in what others say about your abilities, whether it’s negativity or excessive praise. The key is to stay focused on your work.

Sometimes, the most challenging voice to overcome is your own. I’ve often doubted myself and felt like giving up, questioning whether I was good enough. Doubt is a natural part of the process, but it shouldn’t consume you. It’s important to shake off that negative energy and keep marching on.

MEH: Sometimes, single images that are part of a bigger story can be so powerful. Your photo of Joseph saying goodbye to Sudan, for instance.

AV: This was Sudan’s final moment before he died. He was surrounded by love, together with the people who committed their lives to protecting him. I often think back on this moment, and it is the silence that I remember most — a haunting silence that seemed to foreshadow what a world without wildlife would be like. If there is meaning in Sudan’s passing, it’s that all hope is not lost. Our fate is linked to the fate of animals. Sudan showed us that these giants are part of a complex world created over millions of years, and their survival is intertwined with our own. Without wildlife, we all suffer.

This image also showed me the power of photography and that one image can change the world. I spent nine years at that point to document what extinction means for all of us. And this wake-up call to humanity raised more than 2 million dollars for Ol Pejeta Conservancy for rhino conservation. This photo was used over 4.5 million times online for conservation efforts and was named one of National Geographic’s most important images of the 21st century.

MEH: All that time you invested gave the story incredible depth. That’s what we have to do. My 10 trips to North Korea and your 28 trips to Kenya during the pandemic are examples of the commitment needed.

AV: Nobody’s paying for all those trips. You have to take a risk and invest in yourself because if you don’t, you’re betting you’re not going to succeed.

MEH: And definitely not waiting around for the phone to ring with someone on the other end of the line handing you an assignment, as Eve Arnold told me years ago. That was a motivating factor for her “In China” project.

AV: I went to see Eve Arnold in London years ago because she’s one of my great heroes. She must have been 90 years old, and there she was, working on a book. She was so prolific even in her last days.

MEH: We don’t retire.

AV: I was so impressed with her understanding of images’ enduring power and significance. Sometimes, we capture moments without fully grasping their importance at the time.

MEH: History can only be truly understood from the perspective of time.

How To Help

Vital Impacts is a women-led 501(c)(3) non-profit that harnesses the power of art and storytelling to support community-based conservation efforts and elevate visual journalists who are dedicated to sharing impactful environmental narratives. Donations to Vital Impacts support grassroots organizations working to protect endangered habitats and the storytellers who amplify these critical stories.

Donate today and double your impact: To help your donation dollars go further, the Make It Better Foundation is matching all donations, up to $5,000.

More from Better Magazine

- National Geographic Reveals 2024 ‘Pictures of the Year’: Here Are Some of the Most Fascinating

- ‘Together, We Are Making Big Waves’: Pioneering Marine Biologist and National Geographic Explorer Sylvia Earle Says It’s Not Too Late to Save Our Oceans

- Jane Goodall Shares 3 Reasons She’s Optimistic About the Future of the Environment

Assignments have taken award-winning photographer and Make It Better Foundation Director of Photography Mark Edward Harris to more than 100 countries on all seven continents. His books include Faces of the Twentieth Century: Master Photographers and Their Work, The Way of the Japanese Bath, Wanderlust, North Korea, South Korea, Inside Iran, The Travel Photo Essay: Describing A Journey Through Images and his latest, The People of the Forest — a book about orangutans. He proudly supports the Center for Great Apes, the Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation, and the Search Dog Foundation. You can find him on Instagram or his website.