Everyone wants to be forgiving—the idea is rooted in human nature and our desire to connect with others.

And everyone who makes a mistake wants to be forgiven: Look at Chris Brown, Gov. Mark Sanford, and John Edwards, to name just a few examples. But while forgiveness can come with rewards, it also can have its costs.

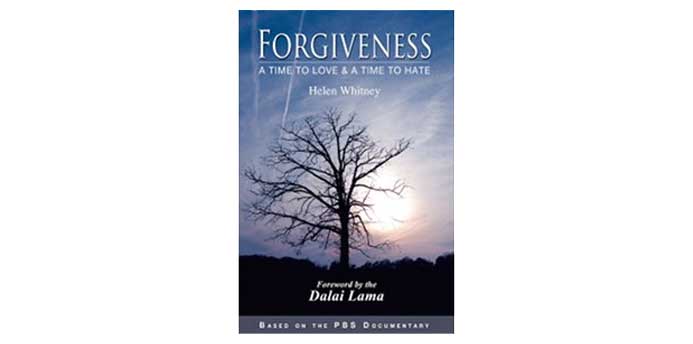

In her new book and PBS mini-series, “Forgiveness: A Time to Love & A Time to Hate,” which airs on two Sundays, April 17 and April 24, acclaimed filmmaker Helen Whitney examines the many ways in which individuals and communities struggle with forgiveness, sometimes arriving at it, sometimes finding it impossible—with good reason.

Make It Better talked with Whitney about how and why we forgive, or don’t.

MIB: What are the dangers of forgiveness?

HW: Giving up anger too quickly or falsely can be harmful. That complicates—as it should—the sentimental notion that it’s always better to forgive and that those who can’t are spiritual underachievers.

On the other hand, righteous anger, or obsessive anger, can be destructive. It’s not easy to be angry in a healthy, creative way; there’s one woman in the book and the film who manages to be angry in a productive way, but that’s rare.

MIB: Scientists are trying to pinpoint the effect of forgiveness on health. Did you see people who forgave getting healthier?

MIB: Scientists are trying to pinpoint the effect of forgiveness on health. Did you see people who forgave getting healthier?

HW: In the book and the film, there’s a woman who contracted HIV from her lover, and was abused by her family. Through a forgiveness intervention in therapy, she let go of her rage and started taking care of herself.

She said to me, “You know what un-forgiveness is like? It’s like renting space in my head—cheap space—having these blaming conversations with people who have hurt me. I realized I gave them that power, and I could take it back.” She’s in glorious health now.

MIB: Do women have a special relationship with forgiveness?

MIB: Absolutely. Within certain religions, particularly Christianity, the woman is seen as the peacemaker, the one who should be forgiving, bringing people together. And as a result, sometimes women are talked back into abusive situations by their religious leaders or even their shrinks.

MIB: When you look at history, there’s so much to apologize for … your examples include apartheid, the Holocaust, and the genocide in Rwanda. Is collective forgiveness possible?

HW: We live in an era of transparency. As a result, apologies are all over. Many public apologies are cheap, but then, there are extraordinary ones. They can change history.

A great example is the Australian apology to the Aborigines. It was years in the making. It wasn’t a quick apology—it was worked on, textbooks were changed, there was contrition, remorse, restitution, and finally, the apology. They put TVs in every public place, and everyone went outside and watched this national event. There were Aborigines in Parliament, and there was weeping.

It’s an apology we should have given to our own aborigines.

MIB: Are there some things that are unforgiveable?

HW: Yes. What forgiveness and un-forgiveness mean is something each of us in our own hearts have to struggle with. There are Holocaust survivors who have forgiven the Nazis. What is unfathomable for one person, for another—for whatever reasons—can be and must be forgiven. There are almost as many meanings for forgiveness as there are for the word love.