Japan holds a very special place in my personal and professional life. I have walked the Nakasendo, hiked the Michinoku Coastal Trail; paddled the mangroves of Amami and Iriomotejima; climbed Mt. Fuji; bathed in countless onsen and sento for my book, “The Way of the Japanese Bath”; documented the Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics in the middle of a global pandemic; and in February and early March of 2024, I will be presenting at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan in Tokyo — with my multiyear focus on eastern Tohoku in the wake of the tsunami caused by the 2011 “Great East Japan Earthquake.”

The Day the Earth Didn’t Stand Still

On March 11, 2011, at 2:46pm J.S.T., an earthquake struck off the coast of Japan. Being on the Ring of Fire, the people of Japan are no strangers to earthquakes. This one, however, from the onset, felt different.

Instead of hitting a peak after a few powerful jolts it kept going and growing, reaching a magnitude 9.0 and unleashing enough seismic force to slightly shorten the length of Earth’s days and knock the entire world off its axis by more than six inches.

The Great East Japan Earthquake — most Japanese simply refer to the tragedy as 3.11 — lasted six terrifying minutes, but the catastrophe was just beginning. Less than an hour later, the first tsunami waves hit the country’s northeastern coastline of Honshu. By the time the water receded, more than 18,000 people had died.

With transportation to Tohoku all but stopped, I enlisted the support of my Tokyo-based colleague Yoshi Ohkuma to gain access to the coastal areas most affected by the tsunami. As we drove from one coastal town to another to document the damage, it became clear how the difference between life and death was often a matter of a few feet.

In the coastal town of Arahama, we saw a two-story kindergarten and community center that doubled as an evacuation center. The tsunami came in further than expected and for many of those on the first floor, the building became a tomb. In Otsuchi, where 1 in 10 people lost their lives, I climbed a seawall to photograph a huge boat resting delicately atop a devastated building like some absurd hat. A few miles to the south in Kamaishi, Yoshi said, “This is what Hiroshima must have looked like.”

In 2012, I returned for the reopening of Spa Resort Hawaiians in Fukushima and then again in 2016 for a 3.11 five-year anniversary story for Vanity Fair, taking a train to Kamaishi and then a taxi to Otsuchi, where I was picked up by Mio Kamitani, secretary general of Oraga-Otsuchi Yumehiroba (Our Field of Dreams), an NGO involved in the rebuilding of Otsuchi. Kamitani’s husband Takuya Ueno, lost his father in the tsunami. As we drove from Otsuchi to Miyako, construction was in full swing on the seawalls and yellow excavators lumbered back and forth, moving millions of pounds of dirt to raise the base height of the surrounding coastal towns before new housing construction could begin.

In 2021 during a break between the Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics I returned for a 10 year anniversary story and in 2023 visited the Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant on a tour organized by Real Fukushima and documented sections of the new Michinoku Coastal Trail with the assistance of the travel company Michinori Tohoku and Tohoku tourism.

While the lives lost on March 11, 2011, will never be replaced, the people of eastern Tohoku have rebuilt their towns, cities and seawalls to safer standards as well as memorialized and interpreted that horrific spring day through state-of-the-art museums to educate future generations.

More From Better:

- 29 of The Best Things to Do in Chicago and the Suburbs This February 2024

- ‘Determined to Prove a Villain’: Paralympian Katy Sullivan Takes on ‘Richard III’ at Chicago Shakespeare Theater

- New In Town: Wagyu House Chicago by the X Pot, All-Day Brunch from Evette’s, Mexican in Soho House, and Artisan Gelato With a Circus Sideshow

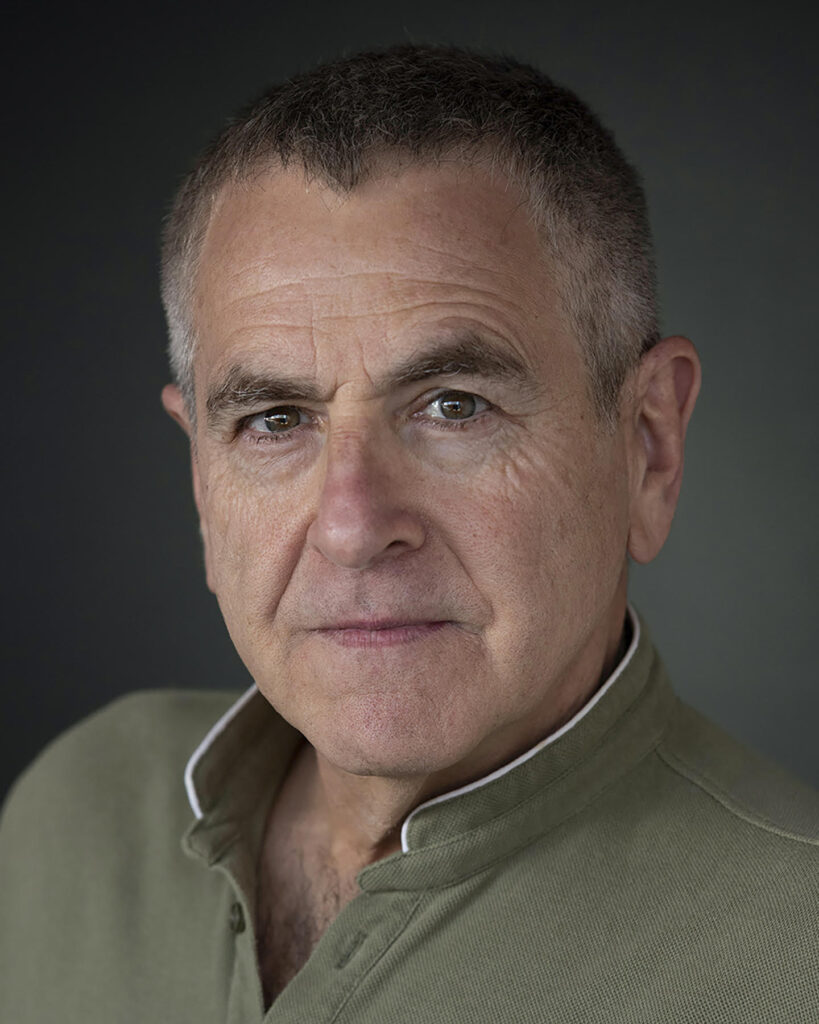

Assignments have taken award-winning photographer and Make It Better Foundation Director of Photography Mark Edward Harris to more than 100 countries on all seven continents. His books include Faces of the Twentieth Century: Master Photographers and Their Work, The Way of the Japanese Bath, Wanderlust, North Korea, South Korea, Inside Iran, The Travel Photo Essay: Describing A Journey Through Images and his latest, The People of the Forest — a book about orangutans. You can find him on Instagram or at his website.