Alzheimer’s, one of the most common forms of dementia, affects more than 6.9 million Americans. It’s a complex and debilitating condition, but for millions of families, Alzheimer’s disease does not arrive as a surprise. It is a genetic condition that researchers can now predict through genetic testing.

A simple genetic test can reveal whether someone carries APOE4, the strongest known genetic risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. People with one copy of APOE4 face up to a fourfold increase in risk. Those with two copies face as much as a fifteenfold increase — comparable to the risk BRCA mutations confer in breast cancer. Nearly 60 percent of people with two APOE4 copies will develop Alzheimer’s during their lifetime.

For decades, this genetic knowledge has offered foresight, but little hope. Yet genetics tells a second, less familiar story — one about protection.

Genetics Protection Against Alzheimer’s

The APOE gene comes in three forms: APOE4, APOE3, and APOE2. While APOE4 increases risk, APOE2 does the opposite. People who carry APOE2 are far less likely to develop Alzheimer’s. Even more striking, many remain cognitively healthy despite accumulating amyloid plaques, a defining feature of the disease.

This protective effect came into sharp focus through a rare genetic discovery known as the Christchurch mutation. Researchers identified it while studying a large extended family in Colombia with a devastating inherited form of Alzheimer’s. In this family, symptoms usually appear in midlife.

But one woman defied the timeline. Although she carried the mutation, she remained mentally sharp until her seventies — more than 30 years later than expected. Brain scans told an even more surprising story. Her brain contained large amounts of amyloid. But there was very little tau pathology — the form of damage most closely linked to memory loss and brain cell death.

Genetic analysis revealed that the Christchurch mutation was in the APOE gene. Thus, in this instance, APOE had acted not as a risk factor but as a remarkable protective factor.

All in all, these findings revealed something profound: Amyloid alone does not predict Alzheimer’s risk. Some forms of APOE can interrupt the chain reaction that turns amyloid into irreversible damage.

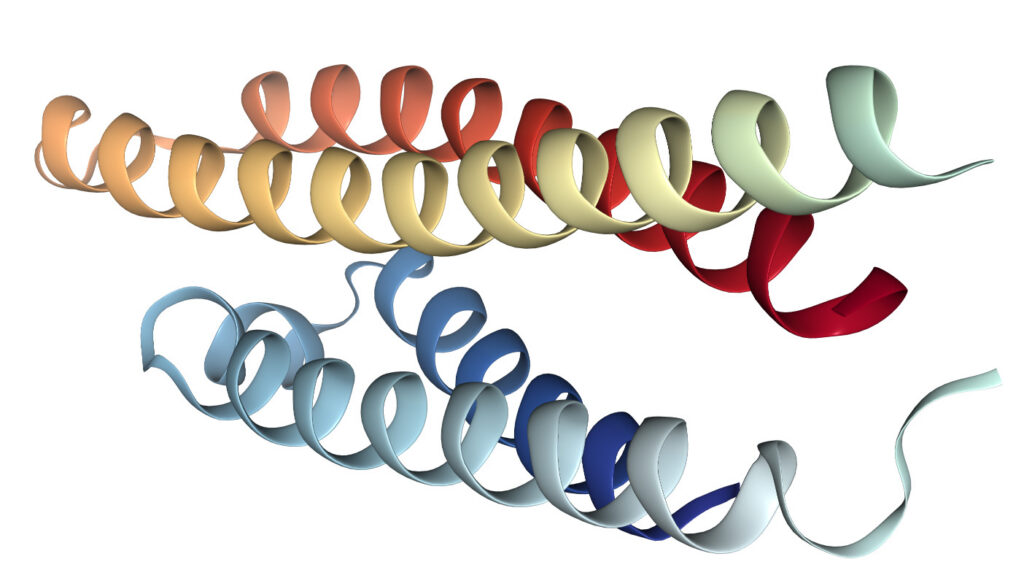

What makes this discovery extraordinary is how small the difference is. APOE is a protein of nearly 300 building blocks. Only two molecular changes separate APOE4, the high-risk form, from APOE2, the protective one. Two tiny shifts can mean the difference between vulnerability and resilience.

Turning Research into Action

Today, researchers at Johns Hopkins Drug Discovery are asking a bold question: What if medicine could tip APOE4 toward behaving more like APOE2? What if genetic risk could be transformed into resistance?

This work is still early, and the challenge is real. APOE has long been considered too complex for traditional drug development. But advances in ultra-large drug screening and human brain models are opening doors once thought closed.

The promise is profound: a future in which Alzheimer’s risk is no longer a genetic sentence, and resilience becomes something medicine can help create.

How to Help

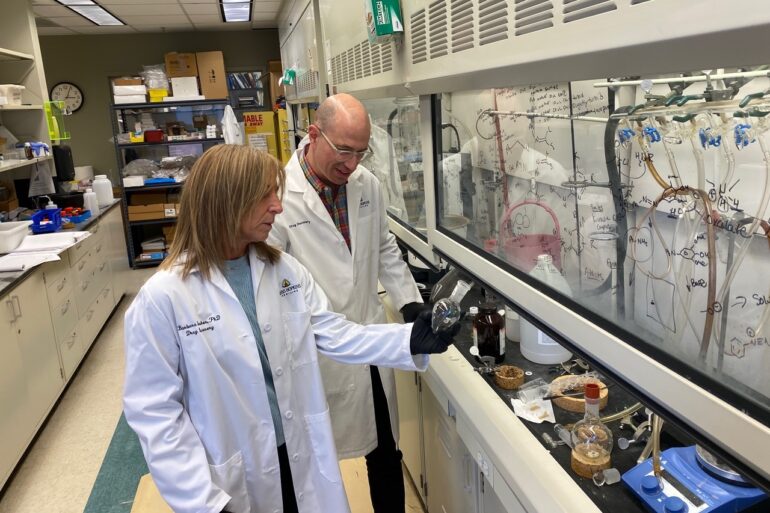

Researchers at Johns Hopkins Drug Discovery are using ultra-large small-molecule libraries and human brain models to discover new drugs that modify APOE4 in the brain — shifting it from a source of Alzheimer’s risk toward biological resistance. Philanthropic support will enable early-stage discovery efforts that industry rarely funds, including large-scale screening, medicinal chemistry, and preclinical testing.

To learn more about the project, please reach out to Dr. Matthew Stremlau at mstreml1@jh.edu. You can also contact Angel Terol, Director of Development, at angel.terol@jhmi.edu.

This post was submitted as part of our “You Said It” program.” Your voice, ideas, and engagement are important to help us accomplish our mission. We encourage you to share your ideas and efforts to make the world a better place by submitting a “You Said It.”

Dr. Barbara Slusher is the Director of Johns Hopkins Drug Discovery and a Professor of Neurology at Johns Hopkins University. A leading translational scientist, she has helped develop four FDA-approved medicines, co-founded five biotechnology companies, and authored more than 250 scientific publications. Her combined experience in academia and industry—including 18 years in senior pharmaceutical leadership—has positioned her to guide discoveries from the laboratory to real-world therapies.

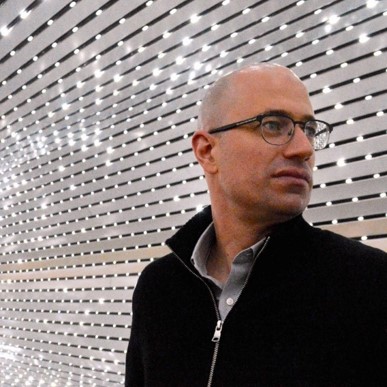

Dr. Matthew Stremlau is the Project Lead for the Hopkins E4 initiative and a biochemist with expertise in Alzheimer’s disease and drug discovery. He has co-founded two biotechnology companies and previously led the development of a novel brain cancer therapy toward IND-enabling studies. Earlier in his career, he discovered the antiviral factor TRIM5 at Harvard University, a breakthrough that explained natural resistance to HIV and earned him Science magazine’s 2007 Grand Prize for Young Life Scientists.